Voyage & Return stories

advertisement

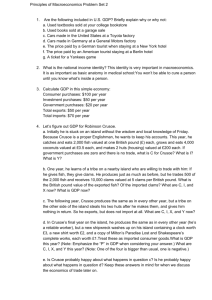

FILE 6 Voyage and Return stories Cast away: surviving on a desert island Look at the illustration: what do you know about the adventures of Robinson Crusoe? TASK 1 Turn an episode of a Voyage and Return story into a graphic novel p. 106 or TASK 2 Breaking news! A group of castaways have just been rescued. Make a radio report about them. p. 106 RECAP Prepare an oral overview of Voyage and Return stories p. 106 → Reading on your own Foe by J.M. Coetzee p. 150 Voyage, parcours initiatique, exil ↑ Robinson Crusoe and Man Friday (1874) 91 Warm up nd a n d a l s i I My September 30, 1659. I, poor miserable Robinson Crusoe, being shipwrecked, during a dreadful storm, in the offing *, came on shore of this dismal unfortunate island, which I called the Island of Despair… Daniel Defoe, Robinson Crusoe (1719) * not far from the land “To say ‘Robinson Crusoe’ is to name one particular book, but it is also to name a type of book, a subgenre. […] Even though it was not the first treatment of a castaway surviving on a desert island, this one subsumed all earlier versions as it has overshadowed all subsequent ones. […] We can define this adventure type, much more than others, in terms of one narration, one plot. It is the story of a man cast away on an island (by a number of possible mechanisms; a man with a number of possible histories) who at first is in danger of dying but gradually learns how to survive, and later how to accumulate goods and crops and comforts, until he is monarch of all he surveys.” Martin Green, Seven Types of Adventure Tales (1991) Robinson Crusoe by N.C. Wyeth, 1920 Puisqu’il nous faut absolument des livres, il en existe un qui fournit, à mon gré, le plus heureux traité d’éducation naturelle. Ce livre sera le premier que lira mon Émile; seul il composera durant longtemps toute sa bibliothèque, et il y tiendra toujours une place distinguée. […] Quel est donc ce merveilleux livre ? Est-ce Aristote ? est-ce Pline ? est-ce Buffon ? Non; c’est Robinson Crusoé. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Émile, ou De l’éducation (1762) 92 FILE 6 Voyage and Return stories A still from the movie Cast Away (2000) ing is terra incognita where anyth “The adventurer enters a rself able to reinvent him or he is e sh or he ere wh , ble possi g, Incognita is an unsettlin or his or her world. Terra it is not only possible but disorienting space where ies. ap, to invent new geograph urgently necessary to rem earrn’.” rning so that we may lea Unmapping means ‘unlea What the novel deals with, as everyone knows, is survival. […] There is the overriding test that Crusoe must answer: is humankind sufficiently developed and selfreliant that, with no other of his species on hand, he will continue to behave like a man. I think the book is, at its most interesting level, a consideration of the extent to which the speciating elements of Homo sapiens hold up under pressure and enable Crusoe to maintain his separateness from the rest of creation. Sebastian Faulks, Faulks on Fiction (2011) ng Men and Empire: Richard Phillips, Mappi e (2000) A Geography of Adventur “The castaway subgenre is significant in that the tales frequently depict colonization as benign—both unavoidable (as the castaway was forced to the island by an act of God, fate, or nature) and legitimate (as most narratives show the island as terra nullius, although indigenous people often join the castaway as Friday does Crusoe). They are narratives of ‘anti-conquest’ in that they ‘seek to secure their innocence in the same moment they assert European hegemony’.” Rebecca Weaver-Hightower, Castaway and Survivor: The Surviving Castaway and Rebirth of Empire (2006) React ct 1. What do these documents tell you about Robinson Crusoe, the novel by Daniel Defoe and Robinson Crusoe, its eponymous hero? 2. What else do you know about the story of Robinson Crusoe? Do you know other stories, real or fictitious, that recall his? 3. Discuss what the word “adventure” means to you and how it can be linked to being stranded on a desert island. 93 Keys and Tools Voyage and Return stories: main features T 5_ 10_ 15_ 20_ 25_ 30_ 35_ 40_ 45_ 94 he essence of the Voyage and Return story is that its hero or heroine (or the central group of characters) travels out of their familiar, everyday “normal” surroundings into another world completely cut off from the first, where everything seems disconcertingly abnormal. At first the strangeness of this new world, with its freaks and marvels, may seem diverting, even exhilarating, if highly perplexing. But gradually a shadow intrudes. The hero or heroine feels increasingly threatened, even trapped: until eventually they are released from the abnormal world and can return to the safety of the familiar world where they began. 50_ There are two obvious categories of stories where the Voyage and Return plot is particularly familiar. The first describes a journey to some land or island beyond the confines of the known or civilized world. The other describes a journey to some more obviously imaginary or magical realm closer to home. […] 65_ Again these stories fall generally into two main types: those where the hero is marooned on some more or less deserted island and those where the land he visits is the home of some strange people or civilization. In the early eighteenth century two of the most famous of such stories were published within two years of each other: one in each category. The first*, in 1719, was that paradigm of all “desert island” stories, Robinson Crusoe. The plot of Defoe’s novel follows the now familiar pattern: as a young sailor whose ship is wrecked, the hero finds himself all alone on a seemingly deserted island. The first half of the story, after Crusoe has recovered from the initial shock, is dominated by his growing confidence as he comes to terms with his plight and with the simple wonders of his unfamiliar new world (e.g. discovering his ability to grow corn and bake bread). Then a shadow intrudes as he sees the imprint of a strange human foot. As Crusoe realizes that he may not be alone on the island, he begins to experience a sense of threat which grows progressively more acute as he finds that his little kingdom is in fact regularly visited by * The second is Gulliver’s Travels, by Jonathan Swift (1721) 55_ 60_ bands of cannibals to pursue their horrid practices. The second half is dominated by the measures Crusoe takes to protect himself; by his gradual recruiting of a little army of runaways (Friday being the first) and finally, as the climax of the tale by leading his followers into a successful battle against the mutinous sailors on a Portuguese ship which has anchored offshore. This culminates in his joyful release, when the grateful captain takes him off the island and back to civilisation. […] The pattern of such a story is likely to unfold like this: 70_ 75_ 80_ 85_ 90_ 95_ 1. Anticipation stage and “fall” into the other world: when we first meet the hero or heroine or central figures, they are likely to be in some state that lays them open to a new shattering experience. Their consciousness is in some way restricted. They may be just young and naïve with only limited experience of the world. They may be more actively curious or looking for something to happen to them… 2. Initial fascination or Dream stage: at first their exploration of this disconcertingly new world may be exhilarating because is it so puzzling and unfamiliar. But it is never a place in which they can feel at home. 3. Frustration stage: gradually the mood of the adventure changes to one of frustration, difficulty and oppression. A shadow begins to intrude which becomes increasingly alarming. 4. Nightmare stage: the shadow becomes so dominating that it poses a threat to the hero or heroine’s survival. 5. Thrilling escape and return: just when the threat closing in on the hero or heroine becomes too much to bear, they make their escape from the other world, back to where they started. At this point, the real question posed by the whole adventure is: how far have they learned or gained anything from their experience? Have they been fundamentally changed or was it all “just a dream”? Christopher Booker, The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories (2004) FILE 6 Voyage and Return stories Read the text 1. Focus on the first paragraph and on lines 62-95. In your own words, define what a Voyage and Return story is and what its pattern is. 2. Explain why Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe is the “paradigm of all ‘desert island’ stories” (l. 32-33). Discuss 3. Discuss why being stranded on a desert island can be a starting point for fiction writing. 4. What can this sort of stories be written for? For whom? → Keep all these elements in mind when reading the texts in the file. Toolbox Voyage and shipwreck journey, passage, travel shipwrecked, castaway marooned, stranded predicament, quandary plight /plaIt/ misfortune hardship Surviving subsist, live through bear /beE/ endure, suffer withstand achieve, earn /∏…n/, gain obtain, prosper, succeed ≠ fail, give up Discovery tour, trip (sea), voyage exploration, investigation search, charting scrutiny, survey adventurous, enterprising daring, risk-taking, audacious, headstrong, intrepid, undaunted ≠ cowardly, fearful, weak Fascination appeal, attraction, charm, enchantment, magic, spell enchanted, idyllic /IdIlIk/, heavenly, flawless Perseverance determination, drive, endurance pluck, resolution, stamina, tenacity, ≠ apathy, idleness /aIdlnIs/, indolence, laziness, lethargy Capable acute, artful, astute, crafty, knowing, sharp, shrewd, smart ≠ incapable, powerless, inept prudent, vigilant, watchful careful, cautious, circumspect, guarded, on the lookout ≠ careless, foolish, heedless, rash, reckless Solitude isolation, loneliness, seclusion ≠ companionship, friendship Hope longing, aspiration, belief, desire, expectation, faith, optimism, wish certainty, confidence, trust reliance /rIlaIEns/ Doubt distrust, faltering, indecision, perplexity, scepticism /skeptIsIzEm/, uncertainty, despair, disbelief, discouragement, hopelessness, pessimism Nightmare fear, anxiety, apprehension, nervousness, alarm, dread, awe /O…/, terror, panic be afraid, scared 95 “Falling” into the other world “Hullo, Robinson Crusoe” Four children, John, Susan, Titty and Roger, are holidaying with their mother on the shores of an unnamed lake in England. They have received permission to set sail in the dinghy Swallow to camp on a deserted island on the lake and have been there for some time. H ullo Man Friday”, said Titty joyfully. “Hullo, Robinson Crusoe,” said Mother. That was the best of Mother. She was different from other natives. You could always count on her to know things like that. 5_ Robinson Crusoe and Man Friday then kissed each other as if they were pretending to be Titty and Mother. “You didn’t expect to see me so soon after yesterday,” said Mother, “but I came to say something to John. I supposed he’s with the rest of the crew in that secret harbor of yours that poor natives are not allowed to see.” 10_ “No. He isn’t on the island just at present,” said Titty. “No one is except me… and now you too.” “So you really are Robinson Crusoe,” said Mother, “and I am Man Friday in earnest. If I’d known that I’d have made a good big footprint on the beach. But where are the others?” 15_ “They’re all right,” said Titty. “They’re coming back again. They’ve gone in Swallow on a cutting-out expedition.” More than that she could not well say, because, after all, Man Friday might be Mother, but she was also a native, even if she was the best native in the world. “I expect they’ve gone to meet the Blackett children,” said Mother. “Man Friday ought not to know anything about them,” said Titty. 20_ “Very well, I won’t,” said Mother. “But what are you doing all by yourself?” “Properly I’m in charge of the camp,” said Titty. “But while they’re not here it does not make any difference if I’m Robinson Crusoe instead.” “I am sure it doesn’t,” said Mother. “Have they left you anything to eat?” “I’ve got my rations in the tent,” said Titty. 25_ “Well, it’s high time you ate them,” said Mother. “Will you let Man Friday put some more wood on the fire and make some tea? I can’t stay very long but perhaps they’ll be back before I go.” “I don’t think they will,” said Titty. “They’ve sailed across the Pacific Ocean. Timbuctoo is nothing to where they’ve gone.” 30_ “Well, I’ll make some tea anyhow,” said Mother. “Let’s see what they’ve left you in the way of rations.” […] When they had eaten their meal, which was a very good one, Robinson Crusoe said, “Now Man Friday, would you mind telling me some of your life before you came to this island?” 35_ Man Friday began at once by telling how she had nearly been eaten by savages, and had only escaped by jumping out of the stew-pot at the last minute. “Weren’t you scalded?” said Robinson Crusoe. “Badly,” said Man Friday, “but I buttered the places that hurt most.” 1. a large farm or ranch 96 And then Man Friday forgot about being Man Friday and became Mother again, and told about her own childhood on a sheep station 1 in Australia, and about emus that laid eggs FILE 6 Voyage and Return stories ↑ Swallows and Amazons directed by Claude Whatham (1974) 40_ 45_ 50_ as big as baby’s heads, and opossums than ran about with their young ones in a pocket in their fronts, and about kangaroos that could kill a man with a kick, and about snakes that hid in the dust. Here Robinson Crusoe, who had forgotten that she was Robinson Crusoe, and had turned into Titty again, talked about the snake which she had seen herself in the cigar-box that was kept in the charcoal-burners’ wigwam 2. Then she told Mother about the dipper 3, and how it had bobbed at her, and flown under water. Then Mother talked about the great drought 4 on the sheep stations, when there was no rain and no water in the wells 5, and the flocks had to be driven miles and miles to get a drink, and thousands and thousands of them died. Then she talked of the pony she had when she was a little girl, and then of the little brown bears that her father caught in the bush, and that used to lick her fingers for her when she dipped them in honey. Time went on very fast, much faster than when Robinson had been alone. Arthur Ransome, Swallows and Amazons (1929) 2. tente recouvrant un four à charbon 3. a species of birds that dive and swim under water 4. long dry rainless period 5. puits Understanding the facts 1. Read the text and explain the situation: main characters, their relationship, place, events. 2. What are the characters actually doing? Say what story Arthur Ransome (1884-1967) Swallows and Amazons established his reputation as one of England’s best writer of children’s books. It is the first of a series of eleven books that tell the continuing adventures of the same characters. The inspiration for the book was drawn from his own childhood experiences and the place in the Lake District where he lived. 5. To what extent can this passage illustrate an episode in a Voyage and Return story? What sort of Voyage and Return story would it be? is being reenacted and how it is being reenacted. Interpreting 3. What worlds are depicted or evoked here? 4. Pick out lines in the text that refer to these various worlds. Say what relations are drawn between those worlds: are they separate / contiguous / intertwined? Reacting 6. Does this scene remind you of personal experiences? Which ones? 7. In your opinion, how can a fictional character’s adventures influence one’s imagination? 97 Dream and fascination “A perpetual summer” R. M. Ballantyne (1825-1894) wrote a hundred or so adventure stories for young people. Their titles (The Young Fur-Traders, Ungava: a Tale of Eskimo Land, The Dog Crusoe and his Master, Fighting the Whales, The Pirate City, The Settler and the Savage, Fighting the Lions…) all evoke action-packed journeys and the thrills of exploration and adventure. Three boys, Ralph Rover (the narrator), Jack Martin and Peterkin Gay, are the sole survivors of a shipwreck on the coral reef of an uninhabited Polynesian island. F or many months after this we continued to live on our island in uninterrupted harmony and happiness. Sometimes we went out a-fishing in the lagoon, and sometimes 5_ went a-hunting in the woods, or ascended to The Coral Island remains Ballantyne’s most famous novel, notably the mountain top, by way of variety, although because it is said to have inspired two other famous Scottish Peterkin always asserted that we went for writers, R. L. Stevenson who wrote Treasure Island in 1881 and the purpose of hailing any ship that might P. M. Barrie who created Peter Pan in 1901. Another reason is its chance to heave in sight. But I am certain direct link with William Golding’s Lord of the Flies (1954), a novel 10_ that none of us wished to be delivered from seen as its antithesis. our captivity, for we were extremely happy, and Peterkin used to say that as we were very young we should not feel the loss of a year or two. Peterkin, as I have said before, was thirteen years of age, Jack eighteen, and I fifteen. But Jack was very tall, 15_ strong, and manly for his age, and might easily have been mistaken for twenty. 20_ 25_ 30_ 35_ 40_ * a group of animals 98 The climate was so beautiful that it seemed to be a perpetual summer, and as many of the fruit-trees continued to bear fruit and blossom all the year round, we never wanted for a plentiful supply of food. The hogs, too, seemed rather to increase than diminish, although Peterkin was very frequent in his attacks on them with his spear. If at any time we failed in finding a drove*, we had only to pay a visit to the plum-tree before mentioned, where we always found a large family of them asleep under its branches. We employed ourselves very busily during this time in making various garments of cocoa-nut cloth, as those with which we had landed were beginning to be very ragged. Peterkin also succeeded in making excellent shoes out of the skin of the old hog, in the following manner. He first cut a piece of the hide, of an oblong form, a few inches longer than his foot. This he soaked in water, and, while it was wet, he sewed up one end of it, so as to form a rough imitation of that part of the heel of a shoe where the seam is. This done, he bored a row of holes all round the edge of the piece of skin, through which a tough line was passed. Into the sewed-up part of this shoe he thrust his heel, then, drawing the string tight, the edges rose up and overlapped his foot all round. It is true there were a great many ill-looking puckers in these shoes, but we found them very serviceable notwithstanding, and Jack came at last to prefer them to his long boots. We also made various other useful articles, which added to our comfort, and once or twice spoke of building us a house, but we had so great an affection for the bower, and, withal, found it so serviceable, that we determined not to leave it, nor to attempt the building of a house, which, in such a climate, might turn out to be rather disagreeable than useful. We often examined the pistol that we had found in the house on the other side of the island, and Peterkin wished much that we had powder and shot, as FILE 6 Voyage and Return stories 45_ 50_ 55_ 60_ 65_ it would render pig-killing much easier; but, after all, we had become so expert in the use of our sling and bow and spear, that we were independent of more deadly weapons. Diving in the Water Garden also continued to afford us as much pleasure as ever; and Peterkin began to be a little more expert in the water from constant practice. As for Jack and I, we began to feel as if water were our native element, and revelled in it with so much confidence and comfort that Peterkin said he feared we would turn into fish some day, and swim off and leave him; adding, that he had been for a long time observing that Jack was becoming more and more like a shark every day. Whereupon Jack remarked, that if he, Peterkin, were changed into a fish, he would certainly turn into nothing better or bigger than a shrimp. Robert Ballantyne, The Coral Island (1857) Understanding the facts 1. Explain what you are told about: – the boys’ routine and the basic needs they fulfill; – the kind of life they are leading; – their relationship. 2. Conclude about how the boys handle their situation and what traits of characters are stressed. Interpreting 3. How does nature appear? What can you say about the characters’ relationship with it? 4. Pick out words or phrases that refer to the image which is given of this island. What is this image? 5. Pick out references to the outside world. How is it seen? What place is it given? 6. Draw conclusions about: – what the boys’ present world is likened to; – the role the boys have in this world. Reacting 7. Discuss whether this passage corresponds to your personal idea of what being stranded on a desert island may offer or imply. 99 A threatening shadow William Golding (1911-1993) a widely acclaimed British novelist, poet, and playwright awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1983. Lord of the Flies, his first novel, made him one of the most important writers in British literature. A running theme in most of his works is man’s fallible nature. “Who thinks there may be ghosts?” A plane carrying a group of British schoolboys has crashed into a desert island, presumably shot down as a war wages on in the outside world. No adult has survived. The children gradually manage to settle and survive. At the start of the following passage, Ralph, who has been made chief from the start, has called a meeting to take stock of the situation. One of the topics they discuss is the beast some younger boys say they have seen. A hushed and anonymous voice broke in. “Perhaps that’s what the beast is—a ghost.” The assembly was shaken as by a wind. 5_ “There’s too much talking out of turn,” Ralph said, “because we can’t have proper assemblies if you don’t stick to the rules.” He stopped again. The careful plan of this assembly had broken down. 10_ “What d’you want me to say then? I was wrong to call this assembly so late. We’ll have a vote on them; on ghosts I mean; then go to the shelters because we’re all tired. No—Jack is it?—wait a minute. I’ll say here and now that I don’t believe in ghosts. Or I don’t think I do. But I don’t like the thought of them. Not now that is, in the dark. But we were going to decide what’s what.” He raised the conch 1 for a moment. “Very well, then. I suppose what’s what is whether there are ghosts or not—” He thought for a moment formulating the question. 15_ “Who thinks there may be ghosts?” For a long time there was silence and no apparent movement. Then Ralph peered into the gloom and made out the hands. He spoke flatly. “I see.” 20_ The world, that understandable and lawful world, was slipping away. Once there was this and that; and now—and the ship had gone 2. The conch was snatched from his hands and Piggy’s voice shrilled. “I didn’t vote for no ghosts!” He whirled round on the assembly. “Remember that all of you!” 25_ 1. a large sea shell; the boys have decided that anyone wishing to speak during a meeting must ask for and be given that sea shell first 2. earlier in the story, a ship went past the island but did not stop as the boys supposed to watch and keep the fire going had gone away to hunt pigs and let it go out 100 They heard him stamp. “What are we? Humans? Or animals? Or savages? What’s grown-ups going to think? Going off—hunting pigs—letting fires out—and now!” A shadow fronted him tempestuously. “You shut up! You fat slug!” 30_ There was a moment’s struggle and the glimmering conch jigged up and down. Ralph leapt to his feet. FILE 6 Voyage and Return stories “Jack! Jack! You haven’t got the conch! Let him speak!” Jack’s face swam near him. 35_ “And you shut up! Who are you, anyway? Sitting there—telling people what to do. You can’t hunt, you can’t sing—” “I’m chief. I was chosen.” 40_ “Why should choosing make any difference? Just giving orders that don’t make any sense—” “Piggy’s got the conch.” “That’s right—favour Piggy as you always do—” 45_ “Jack!” Jack’s voice sounded in bitter mimicry. “Jack! Jack!” “The rules!” shouted Ralph, “you’re breaking the rules!” 50_ “Who cares?” Ralph summoned his wits. “Because the rules are the only thing we’ve got!” But Jack was shouting against him. 55_ “Bollocks to the rules! We’re strong—we hunt! If there’s a beast, we’ll hunt it down! We’ll close in and beat and beat and beat—!” William Golding, Lord of the Flies (1954) ↑ A still from Lord of the Flies, directed by Harry Hook (1990) Understanding the facts 1. Explain what happens during this meeting. 2. “We were going to decide what’s what.” (line 11): what must be decided? What is the general decision? 7. In your opinion, what can the ghost symbolize? 8. What is the main question asked in this passage? What answer is given? 3. Identify the three main characters and focus on them: compare the way they talk, their various reactions and say what their feelings are. 4. Conclude on the mood prevailing on the island. Reacting 9. Do the boys’ behaviours and reactions Interpreting 5. “Once there was this and that; and now—” (lines 19-20): 10. What is threatening them? 11. Who are the characters in the picture? whose comment is this? Explain what is “slipping away”. 6. What would you say the conch stands for? make any sense? Discuss your point of view. What aspects of their personalities and of their relationships are emphasized? 101 Rescue “The end of innocence” H e staggered to his feet, tensed for more terrors, and looked up at a huge peaked cap. It was a white-topped cap, and above the green shade of the peak was a crown, an anchor, gold foliage. He saw white drill, epaulettes, a revolver, a row of gilt buttons down the front of a uniform. […] 5_ The officer looked at Ralph doubtfully for a moment, then took his hand away from the butt of the revolver. “Hullo.” Squirming a little, conscious of his filthy appearance, Ralph answered shyly. “Hullo.” 10_ The officer nodded as if a question had been answered. “Are there any adults—any grown-ups with you?” Dumbly, Ralph shook his head. He turned a half-pace on the sand. A semi-circle of little boys, their bodies streaked with colored clay, sharp sticks in their hands, were standing on the beach making no noise at all. 15_ “Fun and games,” said the officer. The fire reached the coconut palms by the beach and swallowed them noisily. A flame, seemingly detached, swung like an acrobat and licked up the palm heads on the platform. The sky was black. The officer grinned cheerfully at Ralph. 20_ “We saw your smoke. What have you been doing? Having a war or something?” Ralph nodded. The officer inspected the little scarecrow in front of him. The kid needed a bath, a haircut, a nose-wipe and a good deal of ointment. “Nobody killed, I hope? Any dead bodies?” 25_ “Only two. And they’ve gone.” The officer leaned down and looked closely at Ralph. “Two? Killed?” Ralph nodded again. Behind him, the whole island was shuddering with flame. The officer knew, as a rule, when people were telling the truth. He whistled softly. 30_ Other boys were appearing now, tiny tots some of them, brown with the distended bellies of small savages. One of them came close to the officer and looked up. “I’m, I’m—” But there was no more to come. Percival Wemys Madison sought in his head for an incantation that had faded clean away. 35_ The officer turned back to Ralph. “We’ll take you off. How many of you are there?” Ralph shook his head. The officer looked past him to the group of painted boys. “Who’s boss here?” “I am,” said Ralph loudly. 40_ 102 A little boy who wore the remains of an extraordinary black cap on his red hair and who carried the remains of a pair of spectacles at his waist, started forward, then changed his mind and stood still. FILE 6 Voyage and Return stories “We saw your smoke. And you don’t know how many of you there are?” 45_ 50_ “No, sir.” “I should have thought,” said the officer as he visualized the search before him, “I should have thought that a pack of British boys—you’re all British aren’t you?—would have been able to put up a better show than that—I mean—” “It was like that at first,” said Ralph,”before things—” 55_ He stopped. “We were together then—” The officer nodded helpfully. “I know. Jolly good show. Like the Coral Island.” 60_ 65_ Ralph looked at him dumbly. For a moment he had a fleeting picture of the strange glamour that had once invested the beaches. But the island was scorched up like dead wood—Simon was dead— and Jack had… The tears began to flow and sobs shook him. He gave himself up to them now for the first time on the island; great, shuddering spasms of grief that seemed to wrench his whole body. His voice rose under the black smoke before the burning wreckage of the island; and infected by that emotion, the other little boys began to shake and sob too. And in the middle of them, with filthy body, matted hair, and unwiped nose, Ralph wept for the end of innocence, the darkness of man’s heart, and the fall through the air* of the true, wise friend called Piggy. ↑ Lord of the Flies adapted by Nigel Williams (1995) William Golding, Lord of the Flies (1954) * Piggy died after falling off the mountain Understanding the facts 1. Say what this passage depicts; explain what has happened and what the boys have been doing. 2. Focus on the children: how do they appear to the officer? 3. Focus on the officer’s questions and on his reactions to Ralph’s answers: what are his feelings? 4. What do the children do in the last paragraph? Why, in your opinion? Interpreting 5. Compare the officer and the children: what would you say the officer stands for? 6. “I should have thought that a pack of British boys—you’re all British aren’t you?—would have been able to put up a better show than that—I mean—” (lines 48-52): what does the officer mean? 7. Focus on the narrator’s comments on what the children have gone through. What is the nature of these comments? Reacting 8. How can this passage be seen as an illustration of what a Voyage and Return story is intended to do? What is there to learn in that type of story? 103 Landmarks Voyage & Return stories the 18th century. Many exploring expeditions were launched and on their return, captains and mariners had their journals published. The accounts of their voyages described unknown, hardly believable worlds that were nonetheless real. The new lands and people they discovered and the hardships they had to go through sparked readers’ imagination and helped build the picture of the Englishman as ruler of the waves, endowed with an ever triumphant spirit of enterprise and adventure. Origins → Stories of people being stranded on desert islands, or islands inhabited by strange people, go back to Homer’s Odyssey, an epic poem composed around the 8th century BC. It tells the ten-year long voyage that takes Ulysses from Troy to his native island of Ithaca. Ulysses and his sailors are washed up on many islands, meet with all kinds of creatures and manage to escape many perilous situations. The story of Robinson Crusoe is said to have been inspired by the true story of Alexander Selkirk, a Scottish sailor who spent four years as a castaway after being marooned on an uninhabited island, off the coast of Chile, which is now known as Robinson Crusoe Island. Statue of Robinson on Robinson Island Selkirk was rescued by English ships in 1709. Robinson Crusoe’s success is linked to England’s exploration of the Pacific Ocean and the building of the British Empire in 17th Century 18th Century 1611 1719 Shakespeare, The Tempest The island setting is a recurrent element of fiction and is significant insofar as once an island isolates man from civilization, the island itself becomes a minuscule society reflecting a larger one. In The Tempest, Prospero and his daughter Miranda are set adrift by Prospero’s treacherous brother and Prospero in turn shipwrecks his brother onto the island. Shipwreck by Thomas Brich, 1829 104 It is not surprising that the story of Robinson Crusoe that had not been written for children became a tale that grown-ups used again and again to teach children, and mainly boys, what qualities could be expected of them. Daniel Defoe, The Life and Strange Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, a York Mariner Its place in world literature and in British literature in particular is undisputed. It stands out as marking the beginnings of a major new genre, the novel, where common people live lives worth telling and reading about. Its eponymous hero has become “myth” and “archetype”. Several modern themes and meanings can be found in Defoe’s novel: man’s solitude, his place within nature, the Christian notion of Providence, the Anglo-Saxon spirit of conquest, the value of labour over money, cultural relativism, man’s everlasting resilience. 19th Century 1813 1829 Johann David Wyss, The Swiss Family Robinson One of the first and most famous “Robinsonades” or stories inspired by Robinson Crusoe. It was originally written in German. There have been many versions of this story, which shows the Robinsonade’s enormous capacity to adapt to different cultural contexts. Barbara Hofland, The Young Crusoe The “Robinsonade” often has a didactic intent as shown in the story of young Charles Crusoe, wrecked on an island in the Indian Ocean with his father and their Indian servant Sambo. The Young Crusoe’s success illustrates the way it was beginning to focus upon a young boy as hero. FILE 6 Voyage and Return stories William Golding, Lord of the Flies Can be seen as an allegorical novel in which characters, actions and objects are symbols for and represent ideas or abstract concepts, qualities or faults. Political, religious and psycho-analytical allegory can be traced in the novel. Marooned by Howard Pyle, 1909 Arthur Ransome, Swallows and Amazons Since its first publication in 1930, this novel has become part of the school curriculum and interwoven itself into the fabric of English childhood. It is a subtle study of childhood that shows how remarkable characters in history or fiction leave their imprint on children’s minds and consciousness. Derek Walcott, “The Castaway”, a poem, and Pantomime a play. Saint Lucian poet, playwright and writer, 1992 Nobel Prize for Literature. Muriel Spark, Robinson J. G. Ballard, Concrete Island 21th Century 20th Century 1841 1858 R. M. Ballantyne, The Coral Island This novel is seen as the example of the “boys adventure story” as a genre and is also discussed for its various themes: the utopian motif of the desert island, and how they assume their roles and responsibilities. Frederick Marryat, Masterman Ready, or The Wreck of the Pacific Established the adventure story for children as a dominant literary form. It inspired the works of later 19th-century writers, most famously R. M. Ballantyne and R. L. Stevenson. 1930 1954 1965 1974 1978 Modern-day versions of the story of Robinson Crusoe no longer cast children as main characters and are focused with their authors’ concern about man in the 20th or 21th centuries: man’s uncertainty and weakness, his place in an increasingly questionable world, the search for identity, psychological battles for dominance, new perceptions of white men’s history and tales. 2008 J. M. Coetzee, Foe South African novelist and literary critic, 2003 Nobel Prize for Literature. CConnections • The island setting has been transferred to other places, mainly the wilderness. Numerous stories have been written about children or young adults being stranded in deserts or unknown territories notably in Northern America (Catharine Parr Traill, Canadian crusoes (1852); Elizabeth Speare, Sign of the Beaver (1983); Gary Paulsen, Hatchet (1987). • The many adventures that Robinson Crusoe encounters before being marooned and after being rescued makes his tale a maritime story. This aspect of its legacy can be seen in “sea stories”, adventure tales that depict sea voyages, encounters with pirates and natives and search for treasures. Many of them are “coming-of-age” stories. One of the most notable is R. L. Stevenson’s Treasure Island (1883). 105 Over to you! Writing Create a page for a graphic novel In groups, choose an episode in an adventure story linked to Robinson Crusoe, and turn it into a page for a graphic novel. • Write the outline of the episode you want to relate: introduction / event 1 / event 2 / etc. / end • Write out your ideas for what the character(s) will say and decide on how you will tell your story (narrative / direct speech, etc.) • Cast your character(s): their appearances, their personalities… • Choose a drawing style: realistic / schematic / manga / US comics, etc. • Decide on how to present the text: in a balloon with just the face of the speaker showing, or spread out over several frames…? • Decide on the number and shape of frames or panels. Speaking Breaking news! A group of castaways have just been rescued. In groups, make a radio report about that piece of news. Your report can consist of five short audio clips as outlined below: • The presenter introduces the story and each speaker • Speaker no 1: someone at the heart of the story • Speaker no 2: someone from the rescue team • Speaker no 3: an outsider who can give an expert opinion on what happened • The presenter concludes the story. Recap Prepare an oral overview of Voyage and Return stories, remembering what you have learnt in the chapter. Present the documents you have studied, keeping in mind the following elements: • The characteristics of a Voyage and Return story (setting, characters, plot and pattern) • The importance of the story of Robinson Crusoe (the figure of the castaway and castaway narratives) • The appeal of the Voyage and Return story for children and young adults (imagination, adventure, discovery, life away from grown-ups) • The aim of such a story (acquiring experience, learning, warning). 106 Voyage and Return stories Voyage and Return stories Books British literature: Robert Louis Stevenson, Treasure Island (1883), Kidnapped (1886) Rudyard Kipling, Captains Courageous (1897) Joseph Conrad, Lord Jim (1900) Henry De Vere Stacpoole, The Blue Lagoon (1908) Adrian Mitchell, Man Friday (a play) (1973) Derek Walcott, Pantomime (a play) (1978) James Brian Jacques, Castaways of the Flying Dutchman (2001) Going Further FILE 6 Canadian literature: Yann Martel, Life of Pi (2001) American literature: Jefferys Taylor, The Young Islanders: A Tale of Last Century (1842) James Fenimore Cooper, The Crater, or Vulcan’s Peak: A Tale of the Pacific (1847) Herman Melville, Redburn (1849) Jack London, The Sea Wolf (1904) Carol Ryrie Brink, Baby Island (1937) Scott O’Dell, Island of the Blue Dolphins (1960) Gary Paulsen, The Island (1980) Harry Mazer, The Island Keeper (1981) Films Mr. Robinson Crusoe by Edward Sutherland (1932) Las Aventuras de Robinson Crusoe by Luis Buñuel (1954) Robinson Crusoe on Mars by Byron Haskin (1964) Lt. Robin Crusoe, U.S.N. by Byron Paul (1966) Man Friday by Jack Gold (1975) The Blue Lagoon by Randal Kleiser (1980) Six Days, Seven Nights by Ivan Reitman (1998) Cast Away by Robert Zemeckis (2000) The Beach by Danny Boyle (2000) On TV Series: Gilligan’s Island (1960s), Lost (2004), Flight 29 Down, a version of Lost with and for teenagers (2005) Reality shows: Survivor (2000) and Castaway 2000 Cartoons: The Simpsons (Season 9, Episode 14, Das Bus) Listen to Lord of the Flies by Iron Maiden 107