State Ownership Effect on Firms' FDI Ownership Decisions

advertisement

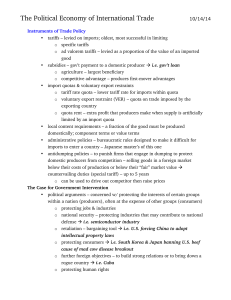

Research Highlights 文章集锦 June 2013 www.IACMR.org State Ownership Effect on Firms’ FDI Ownership Decisions under Institutional Pressure: A Study of Chinese Outward Investing Firms Lin Cui, The Australian National University Fuming Jiang, Curtin University This study investigates the effect of Chinese state ownership on foreign direct investment (FDI) ownership. We argue that state owned-firms are more politically affiliated with the home-country government and more dependent on homecountry institutions for resources. Constituents in the host-country perceive that those dynamics limit the effectiveness of Chinese SOEs. We also argue that firms operating under such resource-dependence and political perceptions tend to conform to rather than resist home- and host-country pressures. We tested our hypotheses using primary data on 132 FDIs made by Chinese firms from 2000 to 2006, and found that when the state entities held higher equity shares in the firm, home regulatory, host regulatory, and host normative pressures exerted stronger pressure on firms to choose joint-ownership structures. External Institutional Pressures Three major external institutional pressures affect FDI decisions. First, within the home-country, firms are subject to the home government’s regulatory restrictions on outward FDI. In emerging economies such as China’s, home-country capital control of outward FDI is prevalent. Similar regulatory restriction may also re-emerge in advanced economies, as governments attempt to impose exit barriers in certain domestic industries. Second, when firms undertake FDI, they are subject to host-country regulatory restrictions on inward FDI. Governments worldwide impose different degrees of restrictions on inward FDI to protect their domestic industries and national interests. While direct bans on inward FDI are increasingly rare, restrictions still discriminate against FDI firms. Third, FDI operations expose firms to pressures from host-country industries and stakeholders. Such pressures depend on how willingness of local players to tolerate different norms exercised by FDI firms. The Effects of State Ownership State ownership increases a firm’s resource-dependence on its home institutions © International Association for Chinese Management Research 1 Research Highlights 文章集锦 and negatively affects its image in the host’s institutional environments. Therefore state ownership moderates the effects of external institutional pressures on FDI ownership decisions. In this study we examine whether state ownership strengthens or weakens the effects of the three types of external institutional pressures determining whether Chinese firms choose joint- or sole-ownership structures in their FDIs. The state ownership effect is so multifaceted that we first discuss its potential effect on FDI ownership decisions. We then examine state ownership for its moderating effect on FDI ownership decisions under external institutional pressures. State ownership direct effects on FDI Government support can grant firms resource advantages in their overseas investments. Apart from received government supports, perceived government backing also differentiates SOEs from other firms in terms of FDI strategic choices. When making strategic decisions, SOEs managers may factor in the possibility that further support will be available in unexpected adverse circumstances. As a result, a higher level of state ownership can increase the likelihood of sole-ownership FDI. An opposite direct effect of state ownership emerges from the political perspective. Being a part of the home-country institutions, SOEs may have noncommercial objectives driven by the state’s political interests and influencing FDI ownership decisions. The Chinese government encourages firms to engage in collaborative FDI to channel foreign countries’ natural, financial, and technological resources back to the domestic economy. A jointownership structure is considered an efficient way to achieve such objectives. The host-country, however, often perceives the state-driven objectives as nonbeneficial, or even harmful. Consequently the hostcountry will impose higher institutional barriers that pressure Chinese SOEs to assume ownership and © International Association for Chinese Management Research June 2013 www.IACMR.org control in their investment, which also increases the likelihood of joint-ownership FDI. Given those opposing effects, we control for the direct effect of state ownership in our analyses. State Ownership and Home Regulatory Institutions Like many other emerging-economy governments, the Chinese government exerts regulatory restrictions on outward FDI to safeguard state assets, to prevent capital flight, and to align direct outward FDI with national interests. Such regulatory restrictions are implemented through an administrative system in which the Ministry of Commerce is authorized as the primary government organization responsible for approving and administering outward FDIs. Its main purposes are to exercise capital control on outward FDI and to direct outward FDI activities to adhere to the government’s international investment strategies. For example, the government attempts to direct outward FDI to acquire foreign technology and natural resources. It also imposes restrictions on the use of foreign exchange to prevent potential problems related to capital flight. Individual firms are likely to encounter varying levels of home regulatory restriction, as the administrative system is evolving constantly across industries to keep pace with China’s rapid development of outward FDI and changes in industrial policy. Home regulatory restriction has a two-fold impact on FDI ownership decisions. First, it pressures firms to follow the practices that have been historically approved by the government. Specifically, during the 1990s when Chinese outward FDI started emerging significantly, the administrative approval process generally required firms to adopt the joint-venture mode. Second, while all outward FDI projects are subject to government approval, projects that involve substantial Chinese capital contribution create greater concerns about capital 2 Research Highlights 文章集锦 flight and foreign exchange demands, and therefore are subject to more strenuous screening processes. Accordingly, Chinese firms find it relatively easier to obtain government approval if the proposed outward FDI is co-funded, ideally with Chinese equity, than if it is fully funded by the Chinese investing firm. Those Chinese home-government pressures affect SOEs. Chinese firms with high levels of state ownership depend heavily on the home country government for critical resources and police support. These firms, especially large SOEs, rely on their relational ties with the government to obtain monopolistic advantages in the home market, and to receive preferential supports when they internationalize. Therefore, state ownership moderates the effect of home-country regulatory restrictions on outward FDI on a firm’s FDI ownership decision, in that the greater the stateentity equity share , the more likely perceived homecountry regulatory restrictions on outward FDI will persuade the firm to choose a joint-ownership structure. State Ownership and Host Regulatory Institutions FDI firms are subject to host-country government regulatory restrictions; that is, formal laws, regulations, and rules to safeguard national interests and maximize local benefits from inward FDI. For example, foreign investors can be subject to various degrees of discriminatory and restrictive policies that impose difficulties in acquiring FDI ownership, limit their access to local resources, require mandatory exporting, and interfere with other operational matters. Such regulatory restrictions force FDI firms to try to equalize their market rights with those of local firms. They can reduce their exposure to regulatory restrictions by forming joint ownerships with local firms, because host regulations are more relaxed for joint-ownership business than for © International Association for Chinese Management Research June 2013 www.IACMR.org exclusively foreign-owned business. While host regulatory restrictions on inward FDI exert pressure to opt for a joint-ownership structure, Chinese state ownership can alter the firm’s response to the pressure. Host-country institutions perceive that firms with concentrated state ownership are not only business entities but are also political actors. As a result, host-country regulatory institutions scrutinize them more strictly, especially in relation to their potential influence on the local economy. They suspect that Chinese SOEs carry political objectives that will be detrimental to shareholders’ commercial interests. Chinese SOEs can also be criticized for being heavily government-subsidized, both directly and indirectly. Thus, state ownership in Chinese investing firms can stimulate politically sensitive and public concerns in host countries, and provoke negative reactions from politicians and the public. Th erefo re, s tate o wn ers h ip mo d er ates restriction effects on FDI ownership. The greater the state share of equity in the firm, the more likely hostcountry regulatory restrictions on inward FDI will cause firms to choose joint-ownership structures. State Ownership and Host Pressures to Conform FDI firms are challenged to meet social expectations that the host countries deem appropriate. First, they may become victims of social stereotyping and discriminatory standards. Joint ownership structure can reduce risk exposure by sharing risks among partner firms. Second, firms are challenged to adjust their business practices in accordance with the host systems. A local business partner, by bringing knowledge of the host country’s practices and cultural norms, can facilitate the learning process. Host country constituents perceive two specific negative political images in Chinese state ownership. First, the image of Chinese state power can override their business images. Many Chinese FDIs involve 3 Research Highlights June 2013 www.IACMR.org 文章集锦 intergovernmental negotiations between the Chinese and host-country governments, which further gives the FDI firms images of being under state power. Carrying the burdensome image of having noncommercial objectives and unfair advantages makes it extremely difficult for the investing firm to create positive perceptions about its practice and culture. Second, state ownership is also associated with the image of bureaucratic practice and inefficiency; that is, state ownership can influence the appointment of former bureaucrats as top management personnel in Chinese firms although they typically lack professional business and management backgrounds. Such managerial arrangements reduce operational efficiency and damage firm performance. Although Chinese SOEs are increasingly and substantially transforming their operations and management, the outcome is still too weak to change the general image. As a result, a Chinese investing firm with substantial state ownership would find it difficult to attain host-country legitimacy. So, under hostcountry normative pressure to attain local legitimacy, an SOE is more likely to conform to host-country normative pressure and dilute its foreign image by choosing joint ownership. Research Method In 2006, we collected data from a survey targeting mainland Chinese firms with outward FDI projects. The population was identified from the 2005 Statistical Bulletin of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment published by the Ministry of Commerce of China, which indicates that, by the end of 2005, approximately 5000 Chinese firms had conducted outward FDI projects. The Chinese government kept the list confidential, so we collected the names manually from multiple sources published by central and provincial Chinese governments.2 We identified 588 firms with full contact details from these sources. We then designed and targeted our questionnaire for the top decision makers in Chinese © International Association for Chinese Management Research outward investing firms. Respondents were senior executives directly in charge of the firm’s outward investment activities at the time of the last FDI entry. We received 132 usable responses from 588 questionnaires sent. The firms represented were top-ranking investing firms revealed in the central government’s statistical bulletin, and those approved by eight eastern provinces that collectively contributed to more than 70% cent of the total outward FDI flow of China. Altogether, the firms represented the major forces of Chinese outward FDI at the time of the survey. FDI ownership decision. We used an equity ownership share of 95% as the cut-off between joint ownership and sole ownership structures. We also used the percentage of equity ownership as an alternative measure of FDI ownership decisions. State ownership. We measured state ownership as the total percentage of equity ownership by the Chinese government and its agencies. Institutional pressures. We used three institutional variables. Home regulatory pressure was measured by two questions related to outward FDI approval and foreign exchange approval procedures respectively. Host regulatory pressure was measured by three items describing host country policy pressure on inward FDI, foreign firm operation, and equity-based market entry. Control variables. We controlled for several variables relating to firm capability, host industry, and transaction cost. Findings Each firm reported its latest FDI entry up to 2006, yielding a sample of 132 independent FDI entries. Among these, 53 had no state ownership, 36 were partially state-owned, and 43 were fully state-owned, for a 45.38% average share of state ownership. Industry distribution showed that 78 firms were in manufacturing; 15 were in natural resource-related industries; and 39 were from other 4 Research Highlights 文章集锦 industries, particularly the service industry. Among all entries, 52 had joint-ownership structures and 80 had sole-ownership structures. In the 52 jointownership cases, the Chinese investing firm had a minority ownership in 11 cases, an equal (50-50) ownership in 10 cases, and a majority ownership in 31 cases. Chinese ownership averaged 82.98% in the 132 FDI entries. We tested our hypotheses using logistic regression. Our dependent variable was given a value of one if the focal FDI entry had a jointownership structure, and a value of zero if it had a sole-ownership structure. The results show that the greater the stateentity share of equity, the more likely home country regulatory restrictions on outward FDI would persuade the FDI firm to choose a joint-ownership structure rather than a sole-ownership structure. The interaction of host regulatory pressure and state ownership was positive and significant: the more equity state entities held, the more likely hostcountry regulatory restrictions on inward FDI would persuade the FDI firm to choose a joint-ownership structure rather than a sole-ownership structure. Also, as expected, host normative pressure and state June 2013 www.IACMR.org ownership had a positive and significant interaction. These results support our third hypothesis, that the greater the state-entity equity share, the stronger the effect of host-country normative pressure to attain local legitimacy by choosing a joint-ownership structure over a sole-ownership structure. Managerial Implications From a managerial standpoint, our study suggests that firms must consider their political affiliations when formulating FDI strategies. The political image associated with state ownership requires group-level solutions. For example, when an individual SOE incurs negative publicity, public media may react with negative stereotyping that impedes other SOEs in their image-building efforts. To change host-country perceptions, SOEs must engage in consistent and coordinated imagebuilding to maximize their benefits. The homecountry government may play a coordinating role in identifying key efforts at country, regional and global levels, and prevent individual firms from free-riding on the positive images built through cooperative efforts. This version is based on the full article, “State Ownership Effect on Firms’ FDI Ownership Decisions under Institutional Pressure: A Study of Chinese Outward Investing Firms ", Journal of International Business Studies, 2012 (43), 264-284. Lin Cui (lin.cui@anu.edu.au) is associate professor at ANU College of Business and Economics, The Australian National University. Fuming Jiang (fuming.jiang@curtin.edu.au) is professor at Curtin Business School, Curtin University. © International Association for Chinese Management Research 5