The World Bank Group Framework and IFC Strategy for

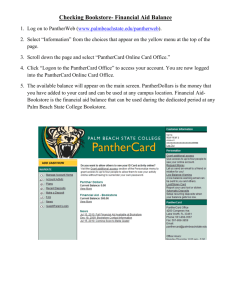

advertisement