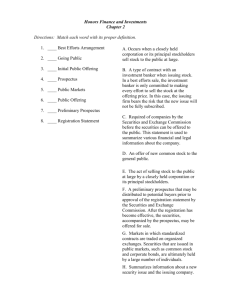

Issuing central bank securities - Handbook No.30

advertisement