File

advertisement

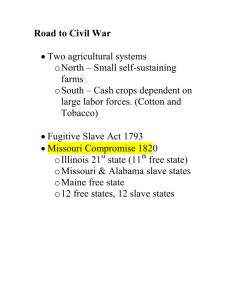

The Georgia Platform From: New Georgia Encyclopedia With the nation facing the potential threat of disunion over the passage of the Compromise of 1850, Georgia, in a special state convention, adopted a proclamation called the Georgia Platform. The act was instrumental in averting a national crisis. Slavery had been at the core of sectional tensions between the North and South. New territorial gains, westward expansion, and the hardening of regional attitudes toward the spread of slavery provoked a potential crisis of the Union, which in many ways portended the tragic events of the 1860s. In 1850, however, compromise and conciliation remained viable alternatives to secession and war. There were many southerners in the decades before the Civil War (1861-65) who preferred disunion to any concessions on slavery for the sake of the Union. These radicals, often known as fire-eaters, called on the South to reject the Compromise of 1850 as an assault on the constitutional right of slavery. As in the nullification crisis of 1832, South Carolina led the protest. Immediate secessionists were numerous throughout Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi. Georgia was best prepared to respond to events, having established a provision for a special convention to deliberate alternatives; the convention, held in Milledgeville, would be a testament to the skill and moderation of a handful of Georgia statesmen. The Georgia Platform established Georgia's conditional acceptance of the Compromise of 1850. Much of the document followed a draft written by Charles Jones Jenkins, who later served as Georgia's governor from 1865 to 1868. The platform established Georgia's conditional acceptance of the Compromise of 1850. Much of the document followed a draft written by Charles Jones Jenkins and represented a collaboration between Georgia Whigs and moderate Democrats dedicated to preserving the Union. In effect, the proclamation accepted the measures of the compromise so long as the North complied with the Fugitive Slave Act and would no longer attempt to ban the expansion of slavery into new territories and states. Northern contempt for these conditions, the platform warned, would make secession inevitable. This qualified endorsement of the Compromise of 1850 essentially undermined the movement for immediate secession throughout the South. Newspapers across the nation credited Georgia with saving the Union. Nevertheless, the conditions upon which the Georgia Platform rested would fail the tests of time, bringing in the next decade a replay of events with different results—secession and war. Compromise of 1850 From: History.com/Compromise of 1850 Divisions over slavery in territory gained in the Mexican-American (1846-48). War were resolved in the Compromise of 1850. It consisted of laws admitting California as a free state, creating Utah and New Mexico territories with the question of slavery in each to be determined by popular sovereignty, settling a Texas-New Mexico boundary dispute in the former’s favor, ending the slave trade in Washington, D.C., and making it easier for southerners to recover fugitive slaves. The compromise was the last major involvement in national affairs of Senators Henry Clay of Kentucky, Daniel Webster of Massachusetts, and John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, all of whom had had exceptional careers in the Senate. Calhoun died the same year, and Clay and Webster two years later. Did You Know? One of the legislative bills that were passed as part of the Compromise of 1850 was a new version of the Fugitive Slave Act. At first, Clay introduced an omnibus bill covering these measures. Calhoun attacked the plan and demanded that the North cease its attempts to limit slavery. By backing Clay in a speech delivered on March 7, Webster antagonized his onetime abolitionist supporters. Senator William H. Seward of New York opposed compromise and earned an undeserved reputation for radicalism by claiming that a “higher law” than the Constitution required the checking of slavery. President Zachary Taylor opposed the compromise, but his death on July 9 made procompromise vice president Millard Fillmore of New York president. Nevertheless, the Senate defeated the omnibus bill. The Missouri Compromise From: History.com/Missouri Compromise In the years leading up to the Missouri Compromise of 1820, tensions began to rise between pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions within the U.S. Congress and across the country. They reached a boiling point after Missouri’s 1819 request for admission to the Union as a slave state, which threatened to upset the delicate balance between slave states and free states. To keep the peace, Congress orchestrated a two-part compromise, granting Missouri’s request but also admitting Maine as a free state. It also passed an amendment that drew an imaginary line across the former Louisiana Territory, establishing a boundary between free and slave regions that remained the law of the land until it was negated by the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. The Missouri Compromise was an effort by Congress to defuse the sectional and political rivalries triggered by the request of Missouri late in 1819 for admission as a state in which slavery would be permitted. At the time, the United States contained twenty-two states, evenly divided between slave and free. Admission of Missouri as a slave state would upset that balance; it would also set a precedent for congressional acquiescence in the expansion of slavery. Earlier in 1819, when Missouri was being organized as a territory, Representative James Tallmadge of New York had proposed an amendment that would ultimately have ended slavery there; this effort was defeated, as was a similar effort by Representative John Taylor of New York regarding Arkansas Territory. Did You Know? For his work on the Missouri Compromise, Senator Henry Clay became known as the “Great Pacificator." The extraordinarily bitter debate over Missouri’s application for admission ran from December 1819 to March 1820. Northerners, led by Senator Rufus King of New York, argued that Congress had the power to prohibit slavery in a new state. Southerners like Senator William Pinkney of Maryland held that new states had the same freedom of action as the original thirteen and were thus free to choose slavery if they wished. After the Senate and the House passed different bills and deadlock threatened, a compromise bill was worked out with the following provisions: (1) Missouri was admitted as a slave state and Maine (formerly part of Massachusetts) as free, and (2) except for Missouri, slavery was to be excluded from the Louisiana Purchase lands north of latitude 36°30′. The Missouri Compromise was criticized by many southerners because it established the principle that Congress could make laws regarding slavery; northerners, on the other hand, condemned it for acquiescing in the expansion of slavery (though only south of the compromise line). Nevertheless, the act helped hold the Union together for more than thirty years. It was repealed by the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which established popular sovereignty (local choice) regarding slavery in Kansas and Nebraska, though both were north of the compromise line. Three years later, the Supreme Court in the Dred Scott case declared the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional, on the ground that Congress was prohibited by the Fifth Amendment from depriving individuals of private property without due process of law. Reconstruction Plans Lincoln’s (Presidential Reconstruction Plan) Abraham Lincoln had thought about the process of restoring the Union from the earliest days of the war. His guiding principles were to accomplish the task as rapidly as possible and ignore calls for punishing the South. In late 1863, Lincoln announced a formal plan for reconstruction: 1. A general amnesty would be granted to all who would take an oath of loyalty to the United States and pledge to obey all federal laws pertaining to slavery. 2. High Confederate officials and military leaders were to be temporarily excluded from the process 3. When one tenth of the number of voters who had participated in the 1860 election had taken the oath within a particular state, then that state could launch a new government and elect representatives to Congress. Johnson’s Reconstruction Plan: The looming showdown between Lincoln and the Congress over competing reconstruction plans never occurred. The president was assassinated on April 14, 1865. His successor, Andrew Johnson of Tennessee, lacked his predecessor’s skills in handling people; those skills would be badly missed. Johnson’s plan envisioned the following: 1. Pardons would be granted to those taking a loyalty oath. 2. No pardons would be available to high Confederate officials and persons owning property valued in excess of $20,000. 3. A state needed to abolish slavery before being readmitted. 4. A state was required to repeal its secession ordinance before being readmitted. Radical Republican (Military) Reconstruction Plan: The postwar Radical Republicans were motivated by three main factors: 1. Revenge — a desire among some to punish the South for causing the war 2. Concern for the freedmen — some believed that the federal government had a role to play in the transition of freedmen from slavery to freedom 3. Political concerns — the Radicals wanted to keep the Republican Party in power in both the North and the South. On the political front, the Republicans wanted to maintain their wartime agenda, which included support for: Protective tariffs Pro-business national banking system Liberal land policies for settlers Federal aid for railroad development