Language Devices 2015

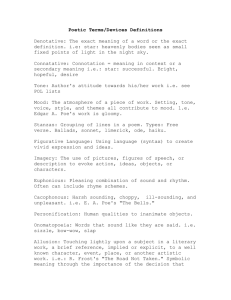

advertisement

Stylistic Terminology *Style: The manner of expression of a particular writer – produced by choice of words (diction), grammatical structures (syntax), use of literary devices (figurative language), and all the possible parts of language usage. Some general styles might include scientific, ornate, plain, emotive. Style is the combination of two elements: the idea expressed and the individuality of the writer. Most writers have their own particular styles. Diction Terminology *Diction: Word choice, particularly as an element of style. Different types and arrangements of words have significant effects on meaning. An essay written in “academic diction” would be much less colorful, but perhaps more precise than “street slang diction.” (NOTE: DO NOT EVER SAY, “The author uses diction.” They all do. We all do. The key is to describe the type of diction used as it applies to the author’s meaning/purpose.) *Abstract Language: Language describing ideas and qualities (honor, beauty, faith) rather than observable or specific things, people, or places. The observable or “physical” is usually described in concrete language. *Concrete Language: Language that describes specific, observable things, people or places, rather than ideas or qualities (Helen of Troy, a leaf, New York City). *Connotation: Rather than the dictionary definition, association suggested by a word; implied meaning rather than literal or denotation. • A stubborn person may be described as being either strong-willed or pig-headed. Although these have the same literal meaning (i.e. stubborn), strong-willed connotes admiration for the level of someone's will, while pig-headed connotes frustration in dealing with someone. *Denotation: The specific, exact meaning of a word, independent of its implications. (Although both house and home have the same denotation, or dictionary meaning, home also has many connotations: comfort, love, security, or privacy.) *Alliteration: The recurrence of initial consonant sounds (or any vowel sounds) in successive or closely associated words or syllables. • Yes, I have read that little bundle of pernicious prose. • “I promise you, the effects he writes of succeed unhappily: as of unnaturalness between the child and the parent; death, dearth, dissolutions of ancient amities.” – Shakespeare • “Apt alliteration’s artful aid is often an occasional ornament in prose.” *Assonance: The use of similar vowel sounds repeated in successive or proximate words containing different consonants. (It’s different from rhyme because rhyme is a similarity of vowel and consonant sounds.) • neigh/fade • “Thy kingdom come, thy will be done.” – The Bible • “A city that is set on a hill cannot be hid.” – The Bible *Cacophony: Harsh, awkward, or dissonant sounds used deliberately in poetry or prose; the opposite of euphony. • “We want no parlay with you and your grisly gang who work your wicked will.” – Winston Churchill *Consonance: The repetition of identical consonant sounds before and after vowel sounds. (Dissonance may be used too.) • boost/best, begun/afternoon, blank/think *Euphony: Succession of harmonious sounds used in poetry or prose; the opposite of cacophony. • Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness, / Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun; / Conspiring with him how to load and bless / With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eves run.” – John Keats *Onomatopoeia: The use of words that sound like what they mean. • hiss, boom, buzz, slam, pop, sizzle, whirr *Elision: The omission of a letter within a word: ne’ver for never; th’ orient for the orient. 1 *Oxymoron: A rhetorical antithesis; a figure of speech composed of contradictory words or phrases. • wise fool, eloquent silence, wonderful nightmare, diabolic love, sad joy • “I do here make humbly bold to present them with a short account of themselves and their art.” – Jonathan Swift • “He was now sufficiently composed to order a funeral of modest magnificence.” – Samuel Johnson *Repetition: Word or phrase used two or more times in close proximity to secure emphasis and add force and clarity to a statement. (Repetition can be repetition of diction and of grammar.) Anadiplosis: A type of repetition where the last word of one phrase, clause, or sentence at or very near the beginning of the next. It can be generated in series for the sake of beauty or to give a sense of logical progression. • “Pleasure might cause her to read, reading might make her know, / Knowledge might pity win, and pity grace obtain.” – Philip Sidney Most commonly, though, anadiplosis is used for emphasis of the repeated word or idea, since repetition has a reinforcing effect. • This treatment plant has a record of uncommon reliability, a reliability envied by every other water treatment facility on the coast. *Anaphora: Repetition of a word, phrase, or clause at the beginning of two or more lines, clauses, or sentences in a row. This is a deliberate form of repetition and helps make the writer’s point more coherent. • “To think on death is misery, / To think on life it is a vanity, / To think on the world verily it is, / To think that here man hath no perfect bliss.” – Peacham • So it has been, so it is now, so it will be. Diacope: Repetition of a word or phrase after an intervening word or phrase: • We will do it, I tell you; we will do it. • “We give thanks to Thee, O God, we give thanks . . .” – The Bible Epanalepsis: Repeating the beginning word of a clause or sentence at the end. The beginning and the end are the two positions of strongest emphasis in a sentence, so by having the same word in both places, you call special attention to it: • Water alone dug this giant canyon, yes, just plain water. • Our eyes saw it, but we could not believe our eyes. Epistrophe: The repetition of the same word or words at the end of successive phrases, clauses or sentences. Epistrophe (also called antistrophe) is thus the counterpart to anaphora. • “Where affections bear rule, there reason is subdued, honesty is subdued, good will is subdued, and all things else that withstand evil, for ever are subdued.” – Wilson • “All the night he did nothing but weep Philoclea, sigh Philoclea, and cry out Philoclea.” – Philip Sidney • The wind howled. The dogs howled. Even the children howled. Epizeuxis: The emphatic repetition of a word. • The best way to describe this portion of South America is lush, lush, lush. • What do you see? Wires, wires, everywhere wires. Symploce: A rhetorical device combining anaphora and epistrophe, so that one word or phrase is repeated at the beginning and another word or phrase is repeated at the end of successive phrases, clauses, or sentences: • To think clearly and rationally should be a major goal for man; but to think clearly and rationally is always the greatest difficulty faced by man. • He was yesterday a great basketball player, he is today a great basketball player, he will tomorrow be a great basketball player. Synonymy: Piling up synonyms for emphasis. • It was a hard, violent, raging, billowing, blasting snowfall. 2 Syntactic Terminology *Syntax: The grammatical arrangement of words in sentences; structure in sentences Anastrophe: Inverting normal or logical grammatical order. • "a midnight clear" (adjective/noun swap) • “Out of the rolling ocean, the crowd, came a drop gently to me, / Whispering, I love you, before long I die” – Whitman *Antithesis: Establishing a clear, contrasting relationship between two ideas by joining them together or juxtaposing them, often in parallel structure. Human beings are inveterate systematizers and categorizers, so the mind has a natural love for antithesis, which creates a definite and systematic relationship between ideas; balancing strongly contrasting words, phrases, clauses, sentences, or concepts. • “To err is human; to forgive, divine.” – Alexander Pope • “That's one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.” – Neil Armstrong *Enumeration: The detailing of parts, causes, effects, or consequences to make a point more forcibly: • When the new highway opened, more than just the motels and restaurants prospered. The stores noted a substantial increase in sales, more people began moving to town, a new dairy farm was started, the old Main Street Theater put up a new building, etc. *Asyndeton: Commas used, with no conjunction to separate a series of words. The parts are emphasized equally when the conjunction is omitted; in addition, the use of commas with no intervening conjunction speeds up the flow of the sentence. Asyndeton takes the form of X, Y, Z as opposed to X, Y, and Z. • Jackie fluttered in confusion, stammered out an explanation, disappeared into the next room. • “government of the people by the people, for the people” – Lincoln • Snow fell, wind howled, trees shook, river froze. *Polysyndeton: Sentence which uses “and” or another conjunction abundantly (usually without commas) to separate the items in a series. Polysyndeton appears in the form of X and Y and Z, stressing equally each member of the series. It makes the sentence slower and the items more emphatic than in asyndeton. • The President must lift our hopes and courage and dreams and lives from the muck. • [Satan] pursues his way, / And swims, or sinks, or wades, or creeps, or flies.” – Milton • Neither mud nor hail nor snow nor rocks nor mountains can stop the All-Terrain 2000. *Balanced Sentence: Sentence that presents two or more contrasting ideas using similar grammatical structures in which both halves of the sentence are about the same length and importance. The structure highlights the contrast in ideas. • “To know her is to love her.” • "The memory of other authors is kept alive by their works. But the memory of Johnson keeps many of his works alive.” – Macaulay *Cumulative sentence: A variation on the loose sentence, the cumulative sentence begins with the main idea and then expands on the idea with layers of descriptive details or other particulars. • “7000 Romaine St. looks itself like a faded movie exterior, a pastel building with chipped art moderne detailing, the windows now either boarded up or paned with chicken-wire glass and, at the entrance, among the dusty oleander, a rubber mat that reads WELCOME.” *Loose Sentence: Sentence that follows the common subject-verb-complement order and concludes with modifying phrases and clauses. A loose sentence can be simple, compound, complex, or compound-complex, but the grammatically complete main idea is always placed at the beginning of the sentence. • The day was hot, with flowers withering under the merciless sun, children running through sprinklers and hiding out in swimming pools, and rampant heat stroke throughout the city. *Periodic Sentence: Sentence in which the main idea appears at the end. This sentence begins with modifying phrases and clauses but withholds the main idea to raise the reader’s expectations and sometimes to build suspense. • At the end of a long trail, which meanders along the Pinamel River through great stands of fir and aspen, by huge boulders that look as if they have tumbled from the peak of the mountains soaring above, under the gaze of unseen deer, rabbits, and even a bear or two, past the old Switley cabin with its caved in roof and broken-down mining equipment, 3 across the grand beaver dam at the neck of Aspen Meadows, beyond the trickling waterfalls formed by the springs that lend the Pinamel sustenance, if not life, sits a worn bench. *Elliptical Sentence: Sentence structure that leaves out something, normally in the second half. Usually, there is a subject-verbobject combination in the first half of the sentence, and the second half of the sentence will repeat the structure but omit the verb and use a comma to indicate the ellipted material. • “If rainy, bring an umbrella.” (The words “it is” and “you” are left out.) *Rhetorical Question: A question that suggests an answer to the reader. • “Well, we can fight it out, or we can run – so, are we cowards?” Syntactic Permutation: Sentence structure that is extraordinarily complex and involved, often difficult for a reader to follow. Freight-train Sentence: Sentence consisting of three or more very short independent clauses. • “There was much game hanging outside the shops, and the snow powdered in the fur of the foxes and the wind blew their tails. The deer hung stiff and heavy and empty, and small birds blew in the wind and the wind turned their feathers.” – Hemingway (Note the two freight train sentences.) Tricolon: Three parallel elements of the same length occurring together in a series. • Her goals were simple yet profound: to sing all day, to sleep all night, to think all year. • “I came, I saw, I conquered.” – Caesar (In this case, being that all three parts are independent clauses, one may also identify the example as a freight train sentence.) Chiasmus: Arrangement of repeated thoughts in the pattern of X Y Y X. Chiasmus is often short and summarizes a main idea; any balance of two elements achieved by reversing the parts in one of them to create an opposing, mirror-like effect. (Antimetabole is one version of chiasmus.) • “Beauty is Truth, Truth Beauty” – Keats • He labors without complaining and without bragging rests. • "Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country." – Kennedy *Inversion: Variation of the normal word order, which puts a modifier or the verb as first in the sentence. The element that appears first is emphasized more. • “To the hounds she rode, with her flags behind her streaming.” • “A damsel with a dulcimer / In a vision once I saw.” – Coleridge *Parallelism: Sentence construction that places in close proximity two or more equal grammatical constructions. • “The Heavens declare the glory of God; / And the firmament showeth His handiwork.” – The Bible • “To work part time, to earn a 4.0 grade point average, and to run for a student body office are my goals.” 4 Figurative Language Terminology *Figurative Language: A word or words that are inaccurate literally but describe by calling to mind sensations or responses that the thing described evokes (a figure of speech, a trope). *Analogy: A comparison of two similar but different things, usually to clarify an action or a relationship. An analogy is a comparison to a direct parallel case. When a writer uses an analogy, he/she argues that a claim reasonable for one case is reasonable for the analogous case. (A simile is an expressed analogy. A metaphor is an implied analogy.) • Comparing the work of a heart to that of a pump. *Image: A word or words, either figurative or literal, used to describe a sensory experience or an object perceived by the senses. An image is always a concrete representation. *Imagery: Words or phrases that use a collection of images to appeal to one or more of the five senses in order to create a mental picture. (NOTE: Don’t say, “The author uses various imageries.” If it’s plural say, “The author uses various images.” *Metaphor: A comparison that imaginatively identifies one thing with another dissimilar thing and transfers or ascribes to the first thing (the tenor or idea) some of the qualities of the second (the vehicle or image). Unlike a simile or analogy, metaphor asserts that one thing is another thing, not just that one is like another. Very frequently a metaphor is invoked by the to be verb. • “She knew the world was a stallion rolling in the blue pasture of ether.” – Hurston • The manager was a ball of energy, zapping around the store recharging everyone's batteries. • Still the private sat, a stone carved from fear and shell shock. Catachresis: An extravagant, implied metaphor using words in an alien or unusual way. While difficult to invent, it can be wonderfully effective. • “I will speak daggers to her.” – Shakespeare • The little old lady turtled along at ten miles per hour. *Conceit: An elaborate figure of speech in which two seemingly dissimilar things or situations are compared. • “Oh to be a pear tree – any tree in bloom! With kissing bees singing of the beginning of the world! She was sixteen. She had glossy leaves and bursting buds and she wanted to struggle with life but it seemed to elude her. Where were the singing bees for her?” – Hurston *Personification: The metaphorical representation of an animal or inanimate object as having human attributes--attributes of form, character, feelings, behavior, and so on. As the name implies, a thing or idea is treated as a person. Technically, this is animation. • The ship began to creak and protest as it struggled against the rising sea. • “Men say they love Virtue, but they leave her standing in the rain.” – Juvenal • After two hours of political platitudes, everyone grew bored. The delegates were bored; the guests were bored; the speaker himself was bored. Even the chairs were bored. Note: A special form of personification, anthropomorphism means specifically giving human characteristics to non-humans, primarily the gods or animals. • My first dog would always jog up to me after school, greeting me with a dopey smile and a friendly word. Metonymy: Another form of metaphor, very similar to synecdoche (and, in fact, some rhetoricians do not distinguish between the two), in which a closely associated object is substituted for the object or idea in mind. • The orders came directly from the White House. • This land belongs to the crown. • Boy, I'm dying from the heat. Just look how the mercury is rising. • You're profiting from the sweat of the poor. (Sweat is part of the image of hard labor.) Synecdoche: A form of metaphor in which the part stands for the whole or the whole for a part. • Farmer Jones has two hundred head of cattle and three hired hands. (Here we recognize that Jones also owns bodies of the cattle, and that the hired hands have bodies attached. This is a simple part-for-whole synecdoche.) • If I had some wheels, I'd put on my best threads and ask for Jane's hand in marriage. 5 *Simile: A figure of speech that uses “like,” “as,” or “as if” to make a direct comparison between two essentially different objects, actions, or qualities. • The soul in the body is like a bird in a cage. • They remained constantly attentive to their goal, as a sunflower always turns and stays focused on the sun. Synaesthesia: Describing one kind of sensation in terms of another, thus mixing senses. • cool green • singing the blues • how sweet the sound *Hyperbole: Deliberate exaggeration in order to create humor or emphasis. Conscious exaggeration used to heighten effect. • “It is always a matter, my darling, of life or death.” – Richard Wilbur • “No; this my hand will rather / The multitudinous seas incarnadine, / Making the green one red.” – Shakespeare *Understatement: Expressing an idea with less emphasis or in a lesser degree than is the actual case. The opposite of hyperbole, understatement is employed for ironic emphasis. • “Last week I saw a woman flay'd, and you will hardly believe how much it altered her person for the worse.” – Swift Litotes: A form of understatement stating the negative of the opposite of what's being affirmed (often with an ironic tone). • The parachute jump wasn't a bad way to celebrate your 90th birthday. • He was an engineer not least among his peers. Meiosis: A form of understatement for humor or emphasis. • It only looks like a three-inch gash. Actually it's a mere scratch. • Crashed my car, lost my wallet, upset my girlfriend, enraged her mom, missed work altogether, found out that I failed my science test – I've had better days. *Symbol: Something that is itself and yet also represents something else, like an idea. For example, a sword may be a sword and also symbolize justice. A symbol may be said to embody an idea. There are two general types of symbols: universal symbols that embody universally recognizable meanings wherever used, such as light to symbolize knowledge, a skull to symbolize death, etc., and invested symbols that are given symbolic meaning by the way an author uses them in a literary work, as the white whale becomes a symbol of evil in Moby Dick or as the green light becomes a symbol of hope in The Great Gatsby. 6 Miscellaneous Terminology *Allegory: An extended narrative in prose or verse in which characters, events, and settings represent abstract qualities and in which the writer intends a second meaning to be read beneath the surface of the story; the underlying meaning may be moral, religious, political, social, or satiric. *Allusion: An indirect reference to another work or famous figure, event or object assumed to be well known enough to be recognized by the reader. Allusion often serves the purpose of establishing a connection between the writer and reader, or to make a subtle point. • “Ave! Old knitters of black wool! Morituri te salutant!” (From Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, the Latin phrase alludes to the times of Caesar and the gladiators: “We who are about to die salute you.”) • “A Daniel come to judgment.”– Shakespeare alluding to the Bible *Ambiguity: An event or situation that may be interpreted in more than one way. Also, the manner of expression of such an event or situation may be ambiguous. Artful language may be ambiguous. Unintentional ambiguity is usually vagueness. Aphorism: A short, often witty statement of a principle or a truth about life. • “In prayer, it is better to have a heart without words than words without heart.” – Gandhi • “Nothing great was ever achieved without enthusiasm.” – Emerson *Aside: A brief speech or comment that an actor makes to the audience, supposedly without being heard by the other actors on stage; often used for melodramatic or comedic effect. • “I am not merry; but I do beguile.” – Shakespeare Burlesque: A work designed to ridicule a style, literary form, or subject matter either by treating the exalted in a trivial way or by discussing the trivial in exalted terms (that is, with mock dignity). Burlesque concentrates on derisive imitation, usually in hyperbolic, ridiculous terms. Literary genres (like the tragic drama) can be burlesqued, as can styles of sculpture, philosophical movements, schools of art, and so forth. Catharsis: The emotional release that an audience member experiences as a result of watching tragedy. Epigram: A concise, witty saying (often used in poetry but sometimes in prose) that either stands alone or is part of a larger work. (It may also refer to a short poem of this type.) • “Always do right. That will gratify some of the people, and astonish the rest.” – Twain • “Here lies my wife: here let her lie! / Now she's at rest — and so am I.” – Dryden Epigraph: A quotation or aphorism at the beginning of a literary work suggestive of theme. Epiphany: (Greek for "to manifest" or "to show") In literature, a sudden, intuitive perception of or insight into the reality or essential meaning of something, usually initiated by some simple, homely, or commonplace occurrence or experience. Epithet: An adjective or adjective phrase appropriately qualifying a subject (noun) by naming a key or important characteristic of the subject, as in "laughing happiness," "sneering contempt," "untroubled sleep," "peaceful dawn," and "life-giving water." Sometimes a metaphorical epithet will be good to use, as in "lazy road," "tired landscape," "smirking billboards," "anxious apple." Aptness and brilliant effectiveness are the key considerations in epithets. • "the wine-dark sea" – Homer • "the snot-green sea” – Joyce (playing on Homer) • “sweet silent thought” – Shakespeare *Euphemism: The substitution of a mild or less negative word or phrase for a harsh or blunt one, as in the use of "pass away" instead of "die." The basic psychology of euphemistic language is the desire to put something bad or embarrassing in a positive (or at least neutral light). Thus many terms referring to death, sex, crime, and excremental functions are euphemisms. Since the euphemism is often chosen to disguise something horrifying, it can be exploited by the satirist through the use of irony and exaggeration. • "Ground beef" or "hamburger" for ground flesh of dead cow • "pre-owned" for used or second-hand • "undocumented worker" for illegal alien 7 Explication: The act of interpreting or discovering the meaning of a text. Explication usually involves close reading and special attention to figurative language. Farce: A light, dramatic composition characterized by broad satirical comedy and a highly improbable plot. (Example: Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest) *Flashback: A device that allows the writer to present events that happened before the time of the current narration or the current events in the fiction. Various methods can be used, including memories, dream sequences, stories or narration by characters, or even authorial sovereignty. (That is, the author might simply say, "But back in Tom's youth. . . ."). Flashback is useful for exposition, to fill in the reader about a character or place, or about the background to a conflict (as seen in The Great Gatsby). *Foil: A character who, by contrast, highlights the characteristics of another character (like Emilia is for Desdemona in Othello). *Foreshadowing: The use of a hint or clue to suggest a larger event that occurs later in the work. *Frame: A narrative structure that provides a setting and exposition for the main narrative in a novel. Often, a narrator will describe where he found the manuscript of the novel or where he heard someone tell the story he is about to relate. The frame helps control the reader's perception of the work, and has been used in the past to help give credibility to the main section of the novel. Two examples of novels with frames are Heart of Darkness and The Great Gatsby. *Hubris: The excessive pride or ambition that leads a tragic hero to disregard warnings of impending doom, eventually causing his or her downfall (like Creon in Antigone). Humours: In medieval physiology, four liquids in the human body affecting behavior. Each humour was associated with one of the four elements of nature. In a balanced personality, no humour predominated. When a humour did predominate, it caused a particular personality. (The Renaissance took the doctrine of humours quite seriously--it was their model of psychology--so knowing that can help us understand the characters in the literature. Falstaff (in Henry IV, Part I), for example, has a dominance of blood, while Hamlet seems to have an excess of black bile.) Here is a chart of the humours, the corresponding elements and personality characteristics: • blood...air...hot and moist: sanguine, kindly, joyful, amorous • phlegm...water...cold and moist: phlegmatic, dull, pale, cowardly • yellow bile...fire...hot and dry: choleric, angry, impatient, obstinate, vengeful • black bile...earth...cold and dry: melancholy, gluttonous, backward, lazy, sentimental, contemplative *Irony: A situation or statement in which the actual outcome or meaning is opposite to what was expected. • Dramatic irony: When a reader is aware of a reality that differs from a character’s perception of reality. • Verbal irony: May occur in the literal meaning of a writer’s words. Lampoon: A crude, coarse, often bitter satire ridiculing the personal appearance or character of a person. (It’s also a verb.) *Motif: A recurring subject, theme, idea, or rhetorical device in an artistic work. (A VERY IMPORTANT TERM!) *Paradox: A seemingly contradictory statement that is actually true. This rhetorical device is often used for emphasis or to attract attention; a statement that, while apparently false or contradictory, contains a deeper meaning or truth. Oxymoron is a word-level form of paradox. • “I never found the companion that was so companionable as solitude.” – Thoreau • Less is more. • “I can resist anything except temptation” – Wilde Parody: A satiric imitation of a work or of an author with the idea of ridiculing the author, his ideas, or work. The parodist exploits the peculiarities of an author's expression – his propensity to use too many parentheses, certain favorite words, or whatever. The parody may also be focused on, say, an improbable plot with too many convenient events. Fielding's Shamela is, in large part, a parody of Richardson's Pamela. 8 Persona: The person created by the author to tell a story. Whether the story is told by an omniscient narrator or by a character in it, the actual author of the work often distances himself from what is said or told by adopting a persona – a personality different from his real one. Thus, the attitudes, beliefs, and degree of understanding expressed by the narrator may not be the same as those of the actual author. Some authors, for example, use narrators who are not very bright in order to create irony. *Point-of-view: The perspective from which a story is presented. Common points of view include the following: • First person narrator: A narrator, referred to as “I,” who is a character in the story and relates the actions through his or her own perspective, also revealing his/her own thoughts. • Stream of consciousness narrator: Like a first person narrator, but instead placing the reader inside the character’s head, making the reader privy to the continuous, chaotic flow of disconnected, half-formed thoughts and impressions as they flow through the character’s consciousness. • Omniscient narrator: A third person narrator, referred to as “he,” “she,” or “they,” who is able to see into each character’s mind and understands all the action. • Limited omniscient narrator: A third person narrator who only reports the thoughts of one character, and generally only what that one character sees. • Objective narrator: A third person narrator who only reports what would be visible to a camera; thoughts and feeling are only revealed if a character speaks of them. Ridicule: Words intended to belittle a person or idea and arouse contemptuous laughter. The goal is to condemn or criticize by making the thing, idea, or person seem laughable and ridiculous. It is one of the most powerful methods of criticism, partly because it cannot be satisfactorily answered ("Who can refute a sneer?") and partly because many people who fear nothing else – not the law, not society, not even God – fear being laughed at. (The fear of being laughed at is one of the most inhibiting forces in western civilization. It provides much of the power behind the adolescent flock urge and accounts for many of the barriers to change and adventure in the adult world.) Ridicule is, not surprisingly, a common weapon of the satirist (like in Swift, Addison, and Twain). Sarcasm: A form of verbal irony, expressing sneering, personal disapproval in the guise of praise. (Oddly enough, sarcastic remarks are often used between friends, perhaps as a somewhat perverse demonstration of the strength of the bond – only a good friend could say this without hurting the other's feelings, or at least without excessively damaging the relationship, since feelings are often hurt in spite of a close relationship. If you drop your lunch tray and a stranger says, "Well, that was really intelligent," that's sarcasm. If your girlfriend or boyfriend says it, that's love – I think.) Satire: A manner of writing that mixes a critical attitude with wit and humor in an effort to improve mankind and human institutions. Ridicule, irony, exaggeration, and several other techniques are almost always present. The satirist may insert serious statements of value or desired behavior, but most often he relies on an implicit moral code, understood by his audience and paid lip service by them. The satirist's goal is to point out the hypocrisy of his target in the hope that either the target or the audience will return to a real following of the code. Thus, satire is inescapably moral even when no explicit values are promoted in the work, for the satirist works within the framework of a widely spread value system. Many of the techniques of satire are devices of comparison to show the similarity or contrast between two items: a list of incongruities, an oxymoron, metaphor, etc. *Setting: The environment in which the action of a fictional work takes place. Setting includes time period (such as the 1890's), the place (such as downtown Warsaw), the historical milieu (such as during the Crimean War), as well as the social, political, and perhaps even spiritual realities. The setting is usually established primarily through description, though narration is used also. *Soliloquy: A speech spoken by a character alone on stage, giving the impression that the audience is listening to the character’s thoughts. • Hamlet’s “To be, or not to be” speech Interior Monologue: Writing that records the conversation that occurs inside a character’s head. Stock character: A standard character who may be stereotyped, such as the miser or the fool, or universally recognized, like the hard-boiled private eye in detective stories. Suspension-of-disbelief: The demand made on audience members to provide some details with their imagination and to accept the limitations of reality and staging (drama); also, the acceptance of the incidents of the plot by a reader or audience. 9 *Tone: The writer's attitude toward his subject; his mood or moral view. A writer can be formal, informal, playful, ironic, and especially, optimistic or pessimistic. While both Swift and Pope are satirizing much the same subjects, there is a profound difference in their tone. Travesty: A work that treats a serious subject frivolously – ridiculing the dignified. Often the tone is mock serious and heavy handed. Verisimilitude: The semblance to truth or actuality in characters or events that a novel or other fictional work possesses. To say that a work has a high degree of verisimilitude means that the work is very realistic and believable. 10 Poetic Terminology *Accent: The stress or emphasis given to a syllable or word. In the word “poetry,” the accent (or stress) falls on the first syllable. *Apostrophe: The device of calling out to an imaginary, dead, or absent person, or to a place, thing, or personified abstraction either to begin a poem or to make a dramatic break in thought somewhere within the poem. • “Thou, Nature, art my goddess.” – Shakespeare • “O World, I cannot hold thee close enough.” – Millay Ballad: A long narrative poem that presents a single dramatic episode, which is often tragic or violent; the two major types of ballads are: • Folk Ballad: one of the earliest form of literature, a folk ballad was usually sung and was passed down orally from singer to singer; its author (if a single author) is generally unknown, and its forms of melody often changed according to a singer’s preference • Literary Ballad: also called an art ballad, this is a ballad that imitates the form and spirit of the folk ballad, but is more polished and uses a higher level of poetic diction (like Keats' “La Belle Dame sans Merci") *Blank Verse: Poetry written in unrhymed iambic pentameter, a favorite form used by Shakespeare. • “The quality of mercy is not strain'd, / It droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven / Upon the place beneath; it is twice blest: / It blesseth him that gives and him that takes.” – Shakespeare *Caesura: A natural pause or break in a line of poetry, usually near the middle of the line. • “How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.” – Browning *Couplet: In a poem, a pair of lines that are the same length and usually rhyme and form a complete thought. • “You beat your pate, and fancy wit will come. / Knock as you please--there's nobody at home.” – Pope Elegy: A formal poem focusing on death or mortality, usually beginning with the recent death of a particular person (like Grey’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard”). *End-stopped: A line of poetry with a pause at the end (signified by a comma, period, colon, semi-colon, question mark, or exclamation point). *Enjambment: The continuation of a complete idea (a sentence or clause) from one line or couplet of a poem to the next line or couplet without a pause. (Enjambment comes from the French word for “to straddle.”) • “I think that I shall never see/A poem as lovely as a tree.” – Kilmer *Foot: two or more syllables together that make up the smallest unit of rhythm in poetry: • iamb – a metrical foot of two syllables, one short (or unstressed) and one long (or stressed). There are four iambs in the line, “Come live/ with me/ and be/ my love,” from a poem by Christopher Marlowe. (The stressed syllables are in bold.) The iamb is the reverse of the trochee. • dactyl (dactylic) – a metrical foot of three syllables, one long (or stressed) followed by two short (or unstressed), as in happily or in the first three feet of the following line from Byron: “Know ye the land where the cypress and myrtle…”(The stressed syllables are in bold.) The dactyl is the reverse of the anapest. (This metrical foot is rarely used today.) • spondee – a metrical foot of two syllables, both of which are long (or stressed) as in pen-knife and heartburn or with “green grass” in the middle of the following line by Rosetti: “Be the green grass above me.” (The stressed syllables are in bold.) spondee is especially useful for emphasis or to add gravity. • anapest – a metrical foot of three syllables, two short (or unstressed) followed by one long (or stressed), as in seventeen and to the moon or in the first three feet of the following line from Cowper: “I am monarch of all I survey.” (The stressed syllables are in bold.) The anapest is the reverse of the dactyl. (The anapest is seldom used except in limericks today.) • trochee – a metrical foot of two syllables, one long (or stressed) and one short (or unstressed). There are four trochees in the eight syllables, “Once up-on a midnight dreary” from Poe’s “The Raven.” (The stressed syllables are in bold.) The trochee is the reverse of the iamb. 11 • An easy way to remember the trochee is to memorize the first line of a lighthearted poem by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, which demonstrates the use of various kinds of metrical feet: “Trochee/ trips from/ long to/ short.” (The stressed syllables are in bold.) The trochee is the reverse of the iamb. *Free Verse: Poetry composed of either rhymed or unrhymed lines that have no set meter. Heroic Couplet: A stanza composed of two rhymed lines in iambic pentameter. • “Let observation with extensive view / Survey mankind, from China to Peru.” – Johnson *Iambic Pentameter: A type of meter in poetry, in which there are five iambs to a line. (The prefix penta- means “five,” as in pentagon, a geometrical figure with five sides. Meter refers to rhythmic units. In a line of iambic pentameter, there are five rhythmic units that are iambs.) Shakespeare's plays often include iambic pentameter, which is the most common type of meter in English poetry. • “But soft!/ What light/ through yon/der win/dow breaks?” – Shakespeare • “A horse!/ A horse!/ My king/dom for/ a horse!” – Shakespeare *Meter: The repetition of a regular rhythmic unit in a line of poetry; meters include the following: • monometer: one foot (rare) • dimeter: two feet (rare) • trimeter: three feet • tetrameter: four feet • pentameter: five feet • hexameter: six feet • heptameter: seven feet (rare) Refrain: A line or group of lines that are periodically repeated throughout a poem (like “Nevermore” in Poe’s “The Raven”). *Rhyme: The occurrence of the same or similar sounds at the end of two or more words. The pattern of rhyme in a stanza or poem is shown usually by using a different letter for each final sound. In a poem with an aabba rhyme scheme, the first, second, and fifth lines end in one sound, and the third and fourth lines end in another. • feminine rhyme – A rhyme that occurs in a final unstressed syllable: pleasure/leisure, longing/yearning. • masculine rhyme – A rhyme that occurs in a final stressed syllable: cat/hat, desire/fire, observe/deserve. • internal rhyme – A rhyme occurring within a line of poetry: “Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered weak and weary” • near rhyme – A rhyme also called approximate rhyme, slant rhyme, off rhyme, imperfect rhyme or half rhyme, a rhyme in which the sounds are similar, but not exact, as in home and come or close and lose. Most near rhymes are types of consonance. Due to changes in pronunciation, some near rhymes in modern English were perfect rhymes when they were originally written in older English. Scansion: The analysis of a poem's meter, this is usually done by marking the stressed and unstressed syllables in each line and then, based on the pattern of the stresses, dividing the line into feet. *Sonnet: A lyric poem that is 14 lines long. Italian (or Petrarchan) sonnets are divided into two quatrains and a six-line “sestet,” with the rhyme scheme abba abba cdecde (or cdcdcd). English (or Elizabethan, or Shakespearean) sonnets are composed of three quatrains and a final couplet, with a rhyme scheme of abab cdcd efef gg. English sonnets are written generally in iambic pentameter. *Stanza: A group of lines in the formal pattern of a poem; types include the following: • couplet: the simplest stanza, consisting of two rhymed lines • tercet: three lines, usually having the same rhyme • quatrain: four lines • cinquain: five lines • sestet: six lines • octave: eight lines 12