CAPITAL PUNISHMENT: RACE, POVERTY & DISADVANTAGE

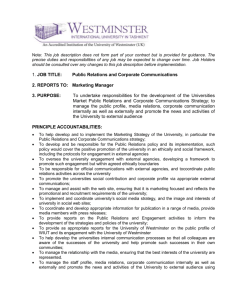

advertisement