THE "PLEASURABLE DECEITS" OF BRONZINO'S SO

advertisement

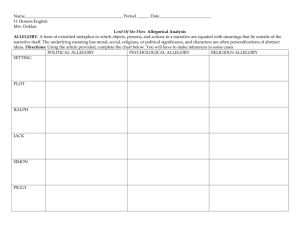

, ~ "'ic' THE "PLEASURABLE DECEITS" OF BRONZINO'S SO-CALLED LONDON ALLEGORY Paul Barolskyand Andrew Ladis - Year in and year out, scholars of Italian Renaissanceart write learned papers in which they attempt to unravel the meaning of Bronzino's so-called London Allegory, also known as Venus,Cupid, Folly, and Time (Fig. 1). Poring over iconographical handbooks and emerging with bits of arcana that promise to make a notorious art-historical sphinx speak, these authors mainly dispute the identities of Bronzino's figures. Is the pretty little girl with a scaly body, leonine paws,and serpent'stail Fraud or Pleasure?Is the nude little imp who scatters roses Jest, Mirth, Folly, or is he Pleasure?Is the raging hag with her hands in her hair Jealousy, Envy, Despair, or evenSyphilis?And what of the most mysteriouspresenceof all-the figure opposite Father Time, who is called Virtue, Night, Oblivion, and Fraud? At the same time, scholars attempt to elucidate the more general theme or themes of the painting. It has been called an allegory of the exposure of luxury, an allegory of vanity, an allegory of virtue and time againstlust, and an allegory of the strife between love and time. No picture of the period is more entrancing or more defeating: an insoluble iconographical conundrum. Although recent scholarshiphas shed light on the painting, in its obsessive pursuit of Bronzino's dramatis personae it neglects to consider the spirit of the work, The scholarship on Bronzino's tour de force has devolved into a joyless academic parlor game, whose purpose is to crack the code of the painter's allegorical language. But such exegesesattempt to understand Bronzino's words with- out hearing his voice. It is a voice whosetone is ironic and disingenuous,rendering muchof the scholarly literature on the painting not, merely inappropriately foreign to its ludic spirit, but perversely lugubrious.! Even though the figures surrounding Venus and Cupid allude to conventional themes of love in literary allegory, their meaning is shaped by the "manner" in which Bronzino fashions his allegory-that is, how Bronzino regards his allegorical figures. In what spirit doeshe refer to all those cliches about love and its tribulations? We would do well to consider the shrewd and telling observationof Sydney Freedberg,who remarked in Painting in Italy: 1500-1600that although based on a complex verbal allegory of love, Bronzino's painting "pretendsa moral demonstrationof which its actual content is the reverse."In other words, the painting is what writers in the sixteenth centurycalled ironico. Yes, the painting alludes to lust, to love and time, to strife and love, to love and jealousy, to love and fraud. But to say that the painting refers predominantly to just one of these possible allegories or that it doessOin a spirit of earnest seriousnessis to oversitn' plify Bronzino's accomplishment and trans' form the painter into a pedant. Given both the apparent playfulnessof Bronzino's painting and the pervasive ironic attitude toward allegory in sixteenth-centuryliterature, why do we go running off to iconographical sourcesfor simple explanationsof Bronzino's presumed allegorical meaning-especial1Y when we find an appropriately jocose ~d mocking attitude toward allegory III Fig. 1 Bronzino, VenZ4 - :ALLED LONDONALLEGO~}' ,dis -- ~ his voice. It is a voice whosetone td disingenuous,rendering muchof rly literature on the painting not lppropriately foreign to its ludic t perversely lugubrious} Even e figures surrounding Venus and ide to conventional themes of love allegory, their meaning is shaped anner" in which Bronzino fashions -:y-that is, how Bronzino regards) ical figures. In what spirit doeshe II those cliches about love and its IS?We would do well to consider i and telling observationof Sydney ;,who remarked in Painting in Italy: I that although based on a complex =gory of love, Bronzino's painting a moral demonstrationof whichits tent is the reverse."In other words, ng is what writers in the sixteenth lied ironico. e painting alludes to lust, to love to strife and love, to love and jealDveand fraud. But to say that the efers predominantly to just one of ;ible allegories or that it does soin : earnest seriousnessis to oversim1Zino's accomplishment and transpainter into a pedant. Given both ent playfulness of Bronzino's painthe pervasive ironic attitude toward n sixteenth-centuryliterature, why ;0 running off to iconographical )r simple explanationsof Bronzino's .allegorical meaning-especially find an appropriately jocose and attitude toward allegory in Fig. 1 Bronzino, Venus,Cupid, Folly, and Time.National Gallery, London 34 Bronzino's own circle? Vasari tells us, for ex~ple, that B~giardini painted an allegory of Night after ~Ichelangelo's figur~ on a tabe~nacle for a Pleta,.an allego? swtable ~o this dark event that mcluded mghtcaps, pillows, bats, ~ .cand!eholder,and ~ ~~te~. ~ven if Vasan IStelling a tall tale, It ISmdlcatwe of a mocking attitude toward allegory. When Michelangelo saw Bugiardini's painting, Vasari claims, he nearly dislocated his jaw from laughter. Michelangelo not only appreciated the amusing fantasy of Bugiardini's unwitting grotesque, but he also laughed at the artist's ludicrous transformation of allegory into farce. In Vasari's story, allegory is burlesqued, turned into a jest or burla. The jest is at the expenseof Bugiardini, who did not know how to use allegory any more than modem scholars of Bronzino know how to read its counterfeit. Bronrino's painting is highly contrived-aTtificioso, as they said in the sixteenth century: flesh like polished marble, ringlets of hair like shavings of gold, the whole brilliant tableau transformed into pierre dure. The painter's artifice is exquisitely self-conscious and playful. Upon Venus's crown sits a golden figurine, whose bent legs and upraised arm parody the goddess'sown posture, thereby making light of the fact that Venus is as artificial in appearance as the very jewelry shewears. Such artifice of form is matched by artifice of meaning. Scholars have sometimesnoted in Bronzino's figure of Venus an allusion to Michelangelo's Doni Tondo. But is the painter merely paying homage to the divine Michelangelo? Is the reference to Michelangelo's Madonna not a form of parody-a sly disrobing of the holy Virgin, who is metamorphosedinto a wanton Venus? And does not the figure's resemblance to Eve in the Sistine Temptation present her in yet a third aspect and make of Venus not only a virgin, but also a fallen woman? Michelangelo, as Vasari says, Was ~self "ambiguous" (ambiguo)and ironic in his utterances, speakingin due sensi. Would he not have appreciated the other sensesof Bronrino's droll and subtle allusions to his work? Throughout the painting, Bronrino is sly and teasing but perhaps nowhere more than in his treatment of the beautiful, enigmatic, and serpentine creature most often called Fraud. Wearing a figuratively revealing robe of couleur changeante,she standspartially but pointedly concealedbehind the candid figure of Jest. We must imagine what is concealed in order to unpuzzle her, but Bronzino is ) himself playing a game of deception-or inKanno,as he might have said-in which truth is far from absolute. Remarking on the "duplicity" of the figure, Panofskysaw her left hand as being attached to her right arm and vice versa. But other, more literal-minded eyes, saw somethingelse. The ambidextrous creature both faces and turns her back to us and in so doing seeminglyhas eachhand correctly attached to its appropriate arm. But are not thosewho seethe painting in this way equally ingannato? To substitute one ambiguity for another is to miss the point, for , Bronzino's inscrutable figure admits-indeed, demands-due sensi. Not only are both interpretations of this evasive monster equallY plausible and equallyuncertain, but such anibiguity and plausibility go to the heart of what the figure means and make her all the more treacherous. In the implausible world of the picture, the only certainty about the figure is its uncertainty, its ability to deceive. Fraud's ambiguity might well remind US that ambiguita, as Castiglione explained, is central to arguzia or wit. Ambiguity resultsin deception, but such deception can be pleasurable when discovered,recognizedthrough thebeholder's own wit. Recal speaksof the illusions of art gann;we might well consider ambiguous, deceptivefigure (] self piacevole. Such pleasure onlyto the painting's form, b toits very meaning. To understandthe painting' beguided by Bronrino's cont vannidella Casa, whose Gal tiglione's Libro del COltegiOi courtlywit. Just as della Casa cismsor motti as "subtle" (sot (artificosi) , so Bronzino pai subtle witticisms. It has 1: Bronzinohas painted Venus the arrow from the quiver 0 disarminghim-so subtly, we notonly was Cupid "ingannat( but so were Bronzino's behc assiduousinterpreter caught (andBronrino's) little game. ] sodelicate and ambiguous,hi cannot state categorically t Venusis simply in the very a ~upid. Might she not also . displayingto us the trophy c Venus'sgesture is allusive, iJ el~ive. Indeed, both "allusiol (like "illusion") are rooted in I andeluderemeans"to fool" or Bronrino's ingegnois so suI asto outwit the viewer. Wh her wide-eyed gaze upor rOW-trophy and weapon, I and metaphor-she radiates and Cupid seems tender an couldthe son have the heart ( OstensiblyapproachingVenu Cupidmakes love to her both ~ h~ fondles her breast, and e kissesher from the rear. : dependsin part upon the S11 .,. - J j I 35 : a virgin, but ~o a fallen _lan~elo, as. Vasan s~ys, \lias :ous ~am~'guo) and ~onjc in pe~g m due senSl.Would ~reclated the othe~ sensesof and subtle allUSIOnsto his thebeholder's.°wn.wit. Recalling that Vasari speaksof th~ illusIons of.art as piacevoli inganni,we might w~ll consider the deliciously aIIlbi~ous, deceptivefigure of .Fraud as herselfp,acevole..S~ch, pleasure IS.centr.at not onlyto the p~tmgs form, but, mextncably, the boy's incipiently serpentine body and makes him a mirror image of Fraud. The analogy is telling. Not only does Cupid deli~tely cradle Venus's head, but, a match for his mother, he also fmgers her bejeweled crown, which, by undetectable deception, he the pamting, ...to BroDZlDois sly t perhaps now~ere m~re than it of the beautiful, eDlgmatic, creature. most ofte? called ~a figuratively revealing robe ~eante,s~e stands par~iallybut :ale~ be~d the c.andidfigure 1StImagme what IS con~aled .puzzle her, but BroDZlDois .a game of deception-or in- ' its very meanmg. To understand the painting'sspirit, we may beguided by Bronzino's contemporary, Giovannidella Casa, whose Galateo (like Castiglione's.Libro del Cortegiano) deals with courtlyWIt. Just as della Casa speaksof witticismsor motti as "subtle" (softili) and "artful" (artificosi) , so Bronzino paints artful and subtle.witticism~. It has been said t~at BroDZlDO has pamted Venus coyly remoVIng the arrow from the quiver of Cupid, hence may intend to expressive remove from head. By contrast to the facesher of the other figures, all of whom comment on the "passioni"of love, the faces of Venus and Cupid are deceptivelyand appropriately impassive, for in this respect they are like the masklike persona of Fraud herself. Gazing upon this highly ironic scene of lovemaking-this ludic liaison dangereuse-wegradually sense the "pleasurable deceits" of the lovers, each unaware of the other's cunning ..f j~ .! I .. i; i' ' I! 1 .I . ! Ight have said-in which truth bsolute. Remarking on the eo figure, Panofskysaw her left ittached to her right arm and : other, more literal-minded thing else. The ambidextrous lceSand turns her back to us seeminglyhas each hand cor. to its appropriate arm. But :'0 seethe painting in this way :to? To substitute one ambier is to miss the point, for utable figure admits-indeed, lensi. Not only are both interhis evasive monster equally (ually uncertain, but sucham. lusibility go to the heart of means and make her all the us. In the implausible world the only certainty about the :rtainty,its ability to deceive. guity might well remind us as C~tiglion~ explained, is a or WIt. Ambiguity results in such deception can be pleascovered,recognized through disarminghim-so subtly, we might add, that notonlywas Cupid "ingannato"by this deceit, but so were Bronzino's beholders until one assiduousinterpreter caught on to Venus's (andBronzino's)little game.Bronzino's wit is sodelicate and ambiguous,however, that we cannot state categorically that Bronzino's Venusis simply in the very act of disarming Cupid. Might she not also ambiguously be displayingto us the trophy of her triumph? Venus'sgesture is allusive, if not ultimately elusive.Indeed, both "allusion" and "elusive" (like "illusion") are rooted in ludere,"to play"; andeluderemeans"to fool" or "to deceive." Bronzino'singegnois so subtle and urbane asto outwit the viewer. While Venus fIXes her wide-eyed gaze upon Cupid's arrow-trophy and weapon, material object and met~phor-she radiates ge~d .passion, and Cupid seems tender and YIelding. But couldthe son havethe heart of a dissemb~er? OstensiblyapproachingVenus from the side, Cupidmakeslove to her both from the.front, ashe fondles her breast, and from behind, as he kisses her from the rear. Suchsottigliezza dependsin part upon the subtle rotation of duplicity. Father Time is usually said to be exposing the very wantonnessthat the beholder is encouraged to enjoy, but is he unveiling the lovers and Jest or the figures behind them? Even exposed,the scenebefore us is so ambiguous that perhaps in this one instance time and the light of day can only tell of halftruth. The scowling Father Time, the ambiguous masklike figure across from him who also ambiguously clutches the blue drapery, and the despairing hag called Jealousyall appear vexed in varying degrees. Are we, however, to share their vexation? Could it just be that Bronzino intended for the courtly beholders of his ironic work to smile at the tribulations or passionsof love? Might we not recall, as the context of ~ro~o's paintin~ the court games .or glUOChl of the sixteenth century, which playfully and am~iguouslymake lir;ht of .the pleasuresand pams of love? The immediate context of.Bro~o's p~ting.is the co~rt of Duke COSImOde MediCI, which Vasarl saw as the mirror image of the court of U rb~o, where suchgameswere played. The courtier, .I t : : f ! l j ; , ;: ': . , l ,l t..: 1: r i ~, l t: !, J : , v r 36 as Castiglione avers, dissembles (from dissimulare)or deceives (from ingannare)by using art that conceals art-the essenceof the sprezzaturathat is central to Bronzino's witty, courtly image. We have in scholarship highly developed studies of the rhetoric or "language of art"-explications of grazia, difficulta, ri/ievo, Juria, fantasia, and many other technical terms. But what of such words as ironico, ambiguo, giuoco, inganno, dissimulare, arguzia, motto, not to mention facezia, burla, belfare, and uccellare? Such terms, like all words associated with art, are a reminder that the theory of art cannot be separated from iconographyany more than iconography can be divorced from style or style from the social circumstancesof art. Were we more sensitiveto this languageof play pervasivein the courts and courtly literature of the cinquecento and to the implications of this language,we might be more attentive to its visual analogues in courtly art, not only in gr()tesques,but in such works as Bronzino's witty London painting, less an allegory as such than an ironic play on allegorical conventions. In the meantime, if we continue to reach for our iconographical handbooks without taking into account the painting's highly ambiguous and highly pleasurable complexityof form and ironic allusion, we will be open to the charge that Michelangelo leveled against certain contemporaries whom he called "solennissimi goffi"-"most solemn clods" or "boobies." Were Bronzino, Michelangelo, della Casa, and Vasari-not to speak of Berni, MoIza, Folengo, and Aretin()-to rise, from the grave and read the solemn, moralizing, and allegorizing iconographical interpretations of Bronzino's coy, ludic London picture now current, they would no doubt smile, if not laugh, at such golfezza-fmding it, in the root senseof golfo, slightly goofy. For recent and a review ., diScussions of the .' of scholarly Bronzmo's literature, . pamtmg see Ins Cheney, "Bronzino's London AUegory: Venus, Cupid, Virtue, and Time," SOURCE6, no. 2 M (Wmter The only literary text that ha Annibale Carracci's Sleeping Chantilly(Fig. 1), is Philostra of the erotes at play (Imaginc cause Philostratus tells u Venus-only that we sel ence2-there is reason to be bale turned his wit and inver ancientsource. A sleepingVenos-Millard standing3-occurs in Claud mium of Palladius and Ce: preface, Claudian's patron a provisea song in honor of a 1-8).The songbegins: It chanced that Venus h t~ed ~to the bosom of a WIth vme to woo sleep NOTE 1. ANNIBALE CARR 1987):12-18; "Bronzmo's London and F Lynette. Allegory: B .osc, h T ..er Love versus une, SOURCE 9, no. 2 (Wmter1990):30-35. cool. ...Slumber . befits h b th row e ml dd ay h ea f '. 0 covermgs, and the through them the gleam (lines 1-7) And while Venus sleeps: Here and there, where'e vites them, repose wing somewake and play or .. plucking dewy apples as ; ...and, poised on their branches to the very tc trees. Others keep guard and drive off the wanton ...and ...amorous PaUl] Given Annibale's penchar froln a variety of sources,s,