Contending With Feminism: Women's Health Issues in Margaret

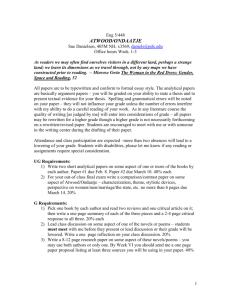

advertisement