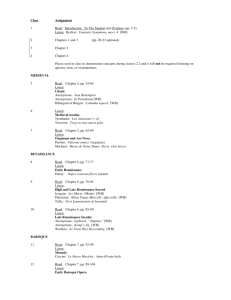

Notes on the Program By Aaron Grad Coriolan Overture, Op. 62

advertisement

Notes on the Program By Aaron Grad Coriolan Overture, Op. 62 LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Born December, 1770 in Bonn Died March 26, 1827 in Vienna Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings Duration: Approximately 8 minutes Composed: 1807 First Performance: March 1807, in Vienna Origins: Heinrich Joseph von Collin’s play Coriolan—not to be confused with Shakespeare’s Coriolanus, based on the same story from Plutarch—debuted in Vienna in 1802. The drama follows a Roman general who defects to the enemy camp and raises an army against Rome, reaching the gates of the city before his mother convinces him to stop. The play was dormant by the time Beethoven wrote his overture in 1807, and his motivation for undertaking the project remains unclear. It may have been meant to draw the attention of the new managers of the imperial theater, including Prince Lobkowitz, who hosted the private concert in March at which Beethoven first offered the overture; it was also possible that Beethoven was courting the playwright for a new opera collaboration. Aside from a one-night revival of Coriolan that April, featuring Beethoven’s music in advance of the play that inspired it, the overture came to audiences as a concert work, encapsulating the dramatic thrust in a single movement. Notes to Notice Beethoven’s condensed portrait of a tortured hero quivers with the taut, muscular energy that is typical of his “middle-period” scores. The choice of key, C minor, foreshadows the fateful Fifth Symphony, composed the following year. Like that symphony, the Coriolan Overture generates powerful emotions from elemental material. The signature motive is a drawn-out C bursting into a short, explosive chord. The unresolved harmonies, like hanging questions, suggest a battle waging within the protagonist’s own conscience. The contrasting theme, a lyrical line in E-flat major, could represent the entreaties of the general’s mother, or his own repressed tenderness for his home city. After a developmental sequence of brittle motives over a running bass line and a return of the opening material, a final whiff of the sweet counter-theme gives way to even more brutal chords and pauses. The last phrases bow out quietly, ending with barren plucks on the keynote. Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op. 36 LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Born December 1770 in Bonn, Germany Died March 26, 1827 in Vienna Instrumentation: 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings Duration: Approximately 32 minutes Composed: 1802 First Performance: April 5, 1803, in Vienna Origins: Beethoven attempted his first symphony in 1795-96, after hearing Haydn’s London symphonies, but he did not complete his Symphony No. 1 until 1800. The following year he began writing his Second Symphony, which he finished in 1802 while living in Heiligenstadt, outside of Vienna. Beethoven had hoped that time in the country might slow his encroaching deafness and improve his spirits, but by the end of his stay he was in a nearly suicidal state of despair. Beethoven re-entered society in Vienna, and soon received a boost in the form of an opera commission. His new association with the Theater an der Wien led to a concert on April 5, 1803, at which he conducted the premiere of the Second Symphony, performed the solo part in the Third Piano Concerto, debuted the oratorio Christ on the Mount of Olives, and reprised his First Symphony. Notes to Notice Adagio molto—Allegro con brio. Beethoven’s Second Symphony begins with a meaty introduction, filled with shifting rhythms, moody harmonies and surprising horn blasts. The Allegro con brio section begins, conversely, with the barest trace of a melody in the lower strings, but it surges to music of an even wilder nature, pounding with off-beat accents and extreme dynamic contrasts. Whereas Haydn loved the elegant dichotomy of forte and piano intensities, Beethoven’s score asks for the even louder fortissimo and even softer pianissimo dynamics, moving beyond tidy Classical style into the more volatile spectrum associated with Romantic music. Larghetto. The Larghetto contrasts the adventurous opening movement with music that is serene, tuneful and unabashedly beautiful. The orchestration demonstrates one of the hallmarks of Beethoven’s symphonic craft: the independence of the woodwinds, which participate fully in the melodic exchanges and harmonic structures, thereby freeing the strings to develop subtle textures and counterlines. Scherzo: Allegro. This bumptious movement marks Beethoven’s first symphonic scherzo, his high-octane answer to Haydn’s more easy-going minuets. Scherzo is Italian for joke, and there is no shortage of humor in the three-note volleys and jarring accents. Allegro molto. The playful spirit carries over into the finale, with its rather rude opening gesture in octaves feeding into polite string figurations. With this music, Beethoven satisfied his debt to Haydn and Mozart and cleared a path for the monumental symphonies to come. Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-flat Major, Op. 73, Emperor LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Born December, 1770 in Bonn Died March 26, 1827 in Vienna Instrumentation: solo piano and orchestra consisting of 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani, and strings Duration: Approximately 38 minutes Composed: 1809 First Performance: November 28, 1811, in Leipzig Origins: In the summer of 1809, Napoleon’s army occupied Vienna for the second time in four years. Beethoven, unlike most of his friends and patrons, remained in the city, and he passed the miserable season with little contact with the outside world. He spent some of that time finishing the Piano Concerto No. 5, his final and most substantial work in the genre. It would also be the only concerto he did not perform himself, given the deteriorated state of his hearing by the time of the 1811 premiere in Leipzig. The Fifth Piano Concerto is in many ways a sibling to the Symphony No. 3, Eroica, also in the key of E-flat. In the case of the concerto, Beethoven had no part in the nickname—Emperor came later from an English publisher—but both works share a monumental posture and triumphant spirit. Beethoven dedicated the concerto to the Archduke Rudolph, the youngest brother of the Austrian emperor Franz. More than just a patron, Rudolph was a piano student of Beethoven’s, and the two maintained a warm friendship until the composer’s death. Notes to Notice Allegro. The Emperor Concerto begins at a climax: the orchestra proclaims the home key with a single chord, and the piano leaps in with a virtuosic cadenza. The ensemble holds back its traditional exposition of the thematic arguments until the pianist completes three of these fanciful solo flights, the last connecting directly to the start of the movement’s primary theme. It is a remarkable structure for a concerto, with an assurance of victory, as it were, before the battle lines have been drawn. Even once the piano returns, the movement continues in a symphonic demeanor, forgoing a standalone cadenza in favor of solo escapades that integrate deftly into the forward progress of the form. Adagio un poco mosso. The slow movement enters in the luminous and unexpected key of B major, with a simple theme first stated as a chorale for muted strings. The piano plays a decorated version over pizzicato accompaniment, and woodwinds later intone the same theme, supported by piano filigree and off-beat string pulses. Rondo: Allegro. The transition back to the home key for the finale is brilliantly understated: the held note B drops to B-flat, providing a smooth lead-in for the piano to introduce the principal theme of the Rondo. The motive’s upward arpeggio generates extra propulsion through its unexpected climax on an accented off-beat, adding a dash of Haydn’s humor to a score that has all the power and majesty of Beethoven in his prime. Orpheus Insight Laura Frautschi, Violinist and Personnel Coordinator In group music making, personal relationships play a vital role. Imagine the dynamics of a string quartet; magnify that ten times, and you have the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra. Every decision, musical and institutional, is made in discussions between colleagues, many of whom have been friends for years. The trust and respect we have for each other is crucial to the Orpheus process, which requires each of us at different times to lead or follow, to compromise or stand firm. Every relationship I have within Orpheus has been enriched by the time the group spends touring. At home in New York, we are all busy with our personal and professional obligations. But when we go on tour, whether it is a bus tour through the southeastern states or an international tour to Asia, time seems to expand and create myriad opportunities for us to catch up, bond, and explore. I have so many wonderful memories of leisurely conversations with a seatmate on the bus, incredible meals shared in Italy and Spain, a baseball game at the Olympic stadium in Nagano, countless late-night ramen runs throughout Japan, and pick-up games of Bananagrams in the airport. There was even one spontaneous performance of the Tchaikovsky Serenade for Strings during an interminable layover! It seems silly to say, “Those who play well together, play well together,” but I believe it to be true. I love going on tour with Orpheus, because of the direct link between the wonderful experiences we share and the magical moments we create on stage. © 2013 Aaron Grad.