Religions of the African Diaspora

advertisement

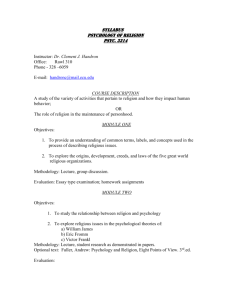

Religions of the African Diaspora Religious Studies 328 Indiana University-Purdue University Instructor: Dr. Kelly Hayes E-mail: keehayes@iupui.edu Office Telephone: 317-278-2639 Office Hours: M: 2:00–3:00 and by appointment (335 Cavanaugh Hall) Semester: Fall 2008 Time: M, W 12:00 p.m. – 1:15 p.m. Location: BS 3012 “There is no worship, there is only a continuing effort to maintain an ongoing relationship between those who have departed and those who remain.”1 COURSE DESCRIPTION Many of the institutions of the modern Western world (capitalism, monetary systems, banking and credit, global trade, even our modern diet of caffeine and sugar) are products of a long process of European exploration and trade beginning in the 15th century. This burgeoning trade linked Europe, the Americas and Africa in an Atlantic world economy in which African slavery was an essential component. The historical development of the modern West thus is intimately linked to the enslavement and forced labor of nearly 12 million Africans brought to the European colonies of the New World over the 300+ year period of the Atlantic slave trade. Today, the social consequences of slavery are manifest in the racism, discrimination, poverty and injustice that persist in the New World societies of North and South America and the Caribbean. In this course we will explore the legacy of the Atlantic slave trade in the Americas by focusing on religion. While we will consider the religious justifications for slavery on the part of slave owners, our primary focus will be on the religions of the enslaved: Africans and their New World descendents. Deprived of home, family, land and community, Africans forcibly transported to the New World brought with them their cultures and their memories, as well as their gods, ancestors and spirits. They fought to hold on to these religious heritages as they forged a new identity in a strange and hostile environment. Adopting the Christianity of their 1 John Mason and Gary Edwards, Four New World Yoruba Rituals, Brooklyn: Yoruba Theological Archministry, 1985, 2. 1 white masters, enslaved Africans adapted it to their own experiences and intentions. Whites were also affected by African religious practices: frequently condemning them as primitive, dangerous or demonic, they also secretly sought out African healers and medicine men. From the conjuncture of master and slave, European and African, emerged new religious forms. The study of these Afro-diasporan religions offers a new perspective on the religious and social history of the Americas, and demonstrates the resilience and creativity of the human spirit in the face of slavery’s brutality. COURSE GOALS 1. To re-examine the religious and social history of the Americas from the perspective of enslaved Africans and their descendents. 2. To appreciate the development and diversity of Afro-diasporan religions by placing them in their social and historical contexts. 3. To explore the historical and contemporary roles of these religions in the lives of their practitioners. 4. To cultivate skills appropriate to the humanities, including the ability to: comprehend, interpret and analyze texts; synthesize information from diverse sources; critically evaluate theories, authors and arguments; and communicate effectively both orally and in writing. REQUIRED TEXTS Chinua Achebe, Things Fall Apart Wade Davis, The Serpent and the Rainbow Curtis Keim, Mistaking Africa: Curiosities and Inventions of the American Mind Joseph Murphy, Working the Spirit: Ceremonies of the African Diaspora Albert Raboteau, Canaan Land: A Religious History of African Americans ADDITIONAL REQUIRED READINGS Additional readings for this course are available as PDF files in the folder titled ―Additional Readings‖ located in the Resources area of Oncourse CL. You will need the appropriate software to open these files from home (Adobe Acrobat or Preview), as well as a fast modem. Therefore it is recommended that you access these readings from campus and either print them out immediately or download them to a disk. These readings are indicated in the class schedule by an asterisk (*). They are listed alphabetically by the author’s last name and the first words of the title, or by the title of the selection if there is no named author. You may also access these readings directly from: http://www.iupui.edu/~womrel/REL%20300%20Spirit/REL%20300_Spirit/ COURSE ORGANIZATION The course is divided into three units, each highlighting a geographic area and (loosely) tracing its development over time: Africa, the United States, and the sugar colonies of Haiti, Cuba and Brazil. We will begin with Africa, considering the stereotypes of Africa that pervade Western culture and impede our understanding of this diverse continent. After working through these stereotypes, we will consider Africa on its own terms, both before and during European colonization, as depicted in Chinua Achebe’s classic novel Things Fall Apart. Building on this ground, in the second unit we will examine the development of Atlantic slavery from the fifteenth through the nineteenth centuries, both from an historical perspective and in the personal 2 experiences of an enslaved African, Olaudah Equiano. Equiano’s description of his native land and its customs invites us to consider African continuities and transformations in slave religions of the United States. As we will see, white slave owners appealed to religion to justify slavery; but religion also provided resources with which slaves created their own communities and resisted, sometimes violently, the dehumanization of enslavement. In the third and final unit, we will examine slavery and the African heritage in Haiti, Cuba and Brazil. Here, the interaction of African and Catholic traditions produced distinctive Afro-diasporan religions that are both like and unlike those of Protestant North America. Attention to the aesthetic aspects and material culture of these religions as expressed in elaborate altars, ritual performances, symbolic objects, ceremonial foods, music, dance and movement demonstrates how these religions connect individual, community and spirit. COURSE FORMAT This course is interdisciplinary in nature, drawing primarily on the fields of history, anthropology and religious studies. We will read and discuss primary sources (slave narratives, ethnographies), secondary sources (scholarly treatments), as well as literature and fiction. Because Afro-diasporan religions emphasize ritual over doctrine, and involve sensory and performative experiences rather than textual study, this course will incorporate visual, auditory and experiential media in the form of film, video, art, music and field trips. Methods used to cover course material include lectures, films, music, slides, guest speakers and, most importantly, class discussion. Short lectures will provide context for the day’s topic, highlighting issues for discussion and critical analysis; these lectures will be informal and open to student input and direction. Periodically we will split-up into smaller discussion groups in order to review and analyze material more thoroughly. Occasionally, students will be asked to lead class discussion, summarize readings, take a pop-quiz, give a brief presentation, engage in group activities, or reflect on the course materials in the form of in-class writing projects. The reading load is moderate to heavy, and students are expected to come to class prepared for discussion and interaction, having read that day’s materials and completed any assignments. There are no examinations in this class; rather, the emphasis will be on the student’s active and ongoing engagement with the course materials, as demonstrated in their homework assignments, participation in discussion (inside and outside of class), and completion of outside assignments and writing projects. The cultivation of skills of creative empathy, critical thinking, interpretation and analysis will be stressed over rote memorization. A final class project will enable students to reflect upon and systematize the course materials, as well as trace the evolution of their learning process. The course is structured as a collective learning endeavor. This means that its success will depend on the full participation of all of its members: the more you put into this class the more you will get out of it. Because everyone brings a different set of experiences, skills and perspectives to the course materials, everyone’s thoughtful contributions advance the collective learning process. Such a process requires a classroom atmosphere of respect, tolerance for dissenting opinions, and a willingness to question received beliefs and to examine biases—one’s own as well as others. My role will be to facilitate this process rather than to impart knowledge for you to passively absorb. While I will guide us through the material and enforce appropriate 3 classroom etiquette, I will not tell you what to think—although I will encourage you to think, and to do so critically. We will encounter some potentially uncomfortable topics: the study of Afro-diasporan religions reveals aspects of American history and society that may challenge, disturb, or provoke. Class discussions are forums in which we will grapple with the issues that the materials present. Your fellow students are also a source of knowledge and support. In addition, I am always available to meet with you on an individual basis to discuss any questions or concerns, either during my office hours or by appointment. Outside of class, the best way to reach me is by e-mail. Please note that you can expect a response to any e-correspondence within twenty-four hours or less during regular business hours; I don’t check e-mail at night or during the weekend. COURSE REQUIREMENTS 1. Readings. Assigned readings should be completed before class. Careful, critical reading of the assigned texts is essential for your understanding of the lectures and for productive class discussion. Suggested readings are just that—they are not required reading, but may be useful to you. 2. Reading Assignments (350 points or 35% of course grade). There will be a variety of assignments given throughout the semester based on the readings. These will take different formats and may include: reading guide questions, summary or analysis of readings, short essay questions, pop quizzes, reflection papers, multi-media assignments, webwork, research, news commentary, creative projects, or other forms of structured engagement with the course materials. The purpose of these assignments is four-fold: a) to ensure that you complete the reading; b) to guide and deepen your reading; c) to provide a structure and common ground for class discussion; d) to connect the course materials with the world outside of the classroom. All written assignments must be typed (double-spaced, 12-point font). They will be collected at random. Late assignments will receive half-credit if turned in by the next class period. Assignments later than that will not be accepted unless you have made prior arrangements with me. 3. Participation (100 points or 10% of course grade). This course is based on collective participation in the learning process, and therefore requires the active participation of all class members. For the purposes of evaluation, the following criteria will be used to evaluate your participation: a. Frequency and clarity of your contributions (oral and written). b. Careful preparation as demonstrated by knowledge of reading assignments and ability to understand and convey the central themes. c. Critical reflection towards ideas and topics presented in the materials under discussion. d. A willingness to approach problems and issues creatively, and to bring personal experience to bear on your comments, where appropriate. 4. Outside Homework (350 points or 35% of course grade). In the Resources area of Oncourse and in the schedule you will find a series of outside homework options that are linked with course topics and/or readings. Each option is worth a different number of points (50 – 100), depending on the complexity and time commitment involved. You are required to turn in a combination of outside homework options totaling 350 points. Which options you choose to complete depends on your schedule and interests. More information about the individual requirements for each option and their due dates is available on Oncourse, in the appropriate folder in the Resources area. 4 5. Final Project (200 points or 20% of course grade). More information about this requirement will be given in class. GRADING A 1,000 point system will be used to evaluate your work, in the following distribution: Reading Assignments 350 points (35% of course grade) Participation 100 points (10% of course grade) Outside Homework 350 points (35% of course grade) Final Project 200 points (20% of course grade) The following percentile scale will be used to determine grades: 90-100 = A; 80-89 = B; 70-79 = C; 60-69 = D; 59 and under = F. The top and bottom two numbers within each grade bracket correspond to plus and minus grade designations, respectively (e.g., 88-89 = B+, 80-81 = B-). ASSIGNMENTS Failure to complete the final project will mean an F mark for the course. All assignments must be submitted on or before the due dates, exceptions only in extraordinary circumstances and with my prior approval. Your absence from class at these times does not in itself grant you an automatic extension. Assignments must be typed, with your name and the date on each page. Please number and staple assignments longer than one page. Late assignments will receive halfcredit if turned in by the next class period. Assignments later than that will not be accepted unless you have made prior arrangements. Students are expected to hand in a hardcopy of their work—do not e-mail me your work—and to save copies of their written work. ATTENDANCE Attendance is mandatory, not optional, and will affect your final course grade. I neither want nor need to know the reason for your absence from class, but be warned that it will have consequences. More than four absences over the course of the semester will lower your final course grade by a half (1/2) latter grade for each subsequent absence (e.g., an A will be decreased to an A-, and so on). Exceptions will be made only in cases of documented hospitalization or grave necessity (such as the death of a close relative). In all cases, attendance should take priority over assignments—do not skip class because you have not completed an assignment! PLAGIARISM AND THE WEB Plagiarism is the use of the work of others without properly crediting the actual source of the ideas, words, sentences, paragraphs, entire articles, music or pictures. Plagiarism is a form of stealing and is a serious offense. Avoid the temptation to plagiarize: DO NOT cut and paste sentences or phrases from the internet or other sources into your written work. Use your own words. Whenever you take words from, or whenever your ideas or expressions have been shaped by, another author or source (other than our class), you must reference these borrowings and contributions using the proper citation format. Today the most common abuses of this rule involve the internet. The quality of the information on the internet is uneven; much of it is dated, anecdotal or biased, and this is especially true in a course that deals with complex theories and 5 controversial religious materials. For this reason, when you consult materials on the internet, you are responsible for evaluating their quality (see: http://www.ulib.iupui.edu/genref/internet.html Relying on flawed information may lower your grade. You must also give citations for every website you use in anyway. If, on assignments, you fail to cite your sources, whether you use page references for books or URLs for websites, I will return your assignment without a grade. To get a grade, you will have to add the necessary references I may use the anti-plagiarism software ―Turnitin.com‖ to guarantee that the work you submit is all your own. A finding of plagiarism will result in a failing grade for that assignment and notification of the appropriate authorities (see Code of Student Rights, Responsibilities and Conduct: http://dsa.indiana.edu/Code/index1.html). CLASS ASSISTANCE If you need assistance, guidance, some reassuring words, or would just like to chat about something pertaining to the course, drop by during office hours or write me an email. Please note that you can expect a response to any e-correspondence within twenty-four hours or less during regular business hours; I do not check e-mail after 5 pm or on weekends. Students With Disabilities The office of Adaptive Educational Services (AES) helps students with disabilities receive appropriate accommodations from the university and their professors. Students need to register with the AES office in order to officially receive such services. 6 COURSE SCHEDULE UNIT ONE: AFRICA August 20 Introduction to the Course August 25 Myths and Stereotypes of Africa Reading: Curtis Keim, Mistaking Africa, chapters 1-2; 10; 12 Assignment: Drawing on the assigned reading, begin to notice how Africa and Africans are portrayed on television, in advertisements, and other cultural references. Bring in at least one example of a common stereotype about Africa or Africans that you found to share with the class. Be prepared to discuss your example and what messages it contains about Africa/Africans as well as what it says about its audience. If possible, bring in the example (i.e., an advertisement from a magazine, etc.). August 27 Reading: September 1 Origins, Tribes and Race Mistaking Africa, chapters 3-5; 8; 11 LABOR DAY (NO CLASS) September 3 Pre-Colonial African Culture: An Overview Reading: *African Religions (50-64) *Igbo Culture and History (xix-xlix) Chinua Achebe, Things Fall Apart, Part I Assignment: Using the assigned readings, please answer the following questions. Use a separate piece of paper and type your answers using complete sentences and incorporating the question into your answer. 1) What are the main characteristics of African religions as described in the first reading ("African Religions")? 2) Identify examples of as many of these characteristics as possible in Part I of Things Fall Apart and briefly describe each, noting the page number where you found them. 3) What elements of Igbo culture and religion strike you as especially interesting, different or unusual? Can you find any parallels in American culture and religion(s)? 4) Is there anything analogous in Christianity to the role of ancestors in traditional African cultures? What could modern, secular society learn from ancestor veneration in African religions? 5) Achebe once explained his work by quoting the following proverb: ―until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.‖ What do you think he meant by this? What is the significance of the metaphor of the hunt? 6) How does Achebe represent African culture and the African landscape in ways that are different from the pervasive Euro-American stereotypes of Africa that we have examined? Give at least two specific examples and discuss them. 7 September 8 Colonial Change Reading: Things Fall Apart, Parts II and III Assignment: Using the assigned readings, please answer the following. Use a separate piece of paper and type your answers using complete sentences and incorporating the question into your answer. 1) What are the sources of misunderstanding between the Igbo and the missionaries? Give specific examples. 2) Who among the Igbo villagers are attracted to the new religion and why? 3) Why do you think that Nwoye converts to Christianity? How does Okonkwo react to Nwoye’s conversion? 4) How does the white man’s law and system of justice differ from that of traditional Umuofia society (review ―Igbo Culture and History‖ pp. xliv-xlvii)? Give specific examples. What function do the kotma, or court messengers, serve in the new society? 5) Why do many in Umuofia feel differently from Okonkwo about the white man’s ―new dispensation‖ (Ch. 21)? In what ways do ―religion and education‖ go ―hand in hand‖ in strengthening the ―white man’s medicine‖? Give specific examples. 6) At the end of the novel, the District Commissioner decides that ―the story of this man who had killed a messenger and hanged himself would make interesting reading,‖ if not for a whole chapter, at least for ―a reasonable paragraph.‖ Taking the perspective of the District Commissioner, write Okonkwo’s story in a paragraph. UNIT II. AFRICANS IN THE AMERICAS: THE UNITED STATES September 10 Atlantic Slavery: The Middle Passage Reading: *Reynolds, ―Human Commerce‖ (13-33); and *Conrad, excerpts from ―Children of God’s Fire‖ (read 1.6; 1.7; 1.8) Suggested: *Thornton, ―Africa: The Source‖ (35-51); and explore the website: http://digital.nypl.org/lwf/english/site/flash.html Outside homework: See Resources area of Oncourse September 15 Slave Narratives: Olaudah Equiano Reading: The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano or Gustavus Vassa, The African, chapters I – II. http://history.hanover.edu/texts/equiano/equiano_contents.html (read chapters I and II) Suggested: http://www.pbs.org/thisfarbyfaith/people/olaudah_equiano.html (more about Equiano) Assignment: Using the assigned readings, please answer the following. Use a separate piece of paper and type your answers using complete sentences and incorporating the question into your answer. 1) Note how Equiano describes his early life. How does he portray Igbo society? What elements does Equiano emphasize? 2) What parallels can you find with Umuofian society in Things Fall Apart? Give specific examples. Do you think Achebe would consider Equiano’s account that of the lion or the hunter? Why? 3) How does Equiano become enslaved? Why are he and his sister enslaved? 4) Equiano becomes a slave to several African masters before he is finally sold to the Europeans. How are these experiences of slavery with African masters different from the slavery he experiences once he leaves Africa? Give specific examples. Outside homework: See Resources area of Oncourse 8 September 17 Crossing the Atlantic Reading: Albert Raboteau, Canaan Land, chapters 1 and 2 Suggested: *Wilmore, ―Black Religious Traditions‖ (285-298) IN CLASS FILM: This Far by Faith vol. I Outside homework: See Resources area of Oncourse September 22 “The Invisible Institution” Reading: Canaan Land, chapter 3 (42-60) Outside homework: See Resources area of Oncourse September 24 Religion and Resistance: Nat Turner’s Rebellion Reading: *Nat Turner’s confession Suggested: William Styron, The Confessions of Nat Turner (on library reserve) Assignment: Using the assigned reading, please answer the following. Use a separate piece of paper and type your answers using complete sentences and incorporating the question into your answer. 1) What is the ―great work‖ that Turner feels himself called to do? 2) How does he become convinced that he has been chosen? 3) What do you think Turner meant when he said that the Spirit appeared to him and said: ―Christ had laid down the yoke he had borne for the sins of men, and that I should take it on and fight against the Serpent, for the time was fast approaching when the first should be last and the last should be first‖? 4) To whom is Turner comparing himself? Who represents the Serpent? 5) In Christian belief, when is the time ―when the first shall be last and the last first‖? 6) What is the role of religion (i.e., religious imagery, religious belief, religious inspiration, etc) in Turner’s decision to lead an uprising? Outside homework: See Resources area of Oncourse September 29 Emancipation and Migration Reading: Canaan Land, chapters 4 and 5 Suggested: http://www.inmotionaame.org/migrations/landing.cfm?migration=6 (Great Migration) Assignment: 1) How does African American life change after the Civil War? 2) What are the religious responses to these changes? 3) What new religious forms emerge among African Americans as a result of the Great Migration and urban life in the North? Discuss at least two different examples. 4) What are the different understandings of race and racism among the UNIA, the Black Jews and the Black Muslims? How does each group define black people and their origins differently? Give specific examples for each. Outside homework: See Resources area of Oncourse POSSIBLE FIELDTRIP TO AME CHURCH October 1 Reading: Freedom Struggles and Black Pride Canaan Land, chapters 6 and 7 9 UNIT III. AFRICANS IN THE AMERICAS: HAITI, CUBA, AND BRAZIL October 6 Reading: Haiti *Desmangles, ―Historical Setting,‖ and Wade Davis, Serpent and the Rainbow, pp.189-206 Suggested: *Catholicism: An Overview (esp. if you don’t know anything about Catholicism) Assignment: Using the assigned reading, please answer the following. Use a separate piece of paper and type your answers using complete sentences and incorporating the question into your answer. 1) In brief, what is the history of the relationship between the island Columbus called Hispaniola and various European powers during the colonial period? What kind of social structure develops as a result? 2) Why were the religious practices of the blacks a cause for alarm among the colonists? 3) What is a maroon, and what was the role of maroons in the Haitian Revolution? 4) What was the role vodou played in the Haitian Revolution? 5) How did Haiti’s economic, political and social systems change after the Revolution? 6) What was the attitude of Haiti’s new black leaders towards vodou? 7) Why did American troops occupy Haiti? 8) What is the relationship between vodou and the Catholic church in Haiti today? Outside Homework: See Resources area of Oncourse October 8 Reading: Vodou Joseph Murphy, Working the Spirit, chapter 2 and *―The Lwa‖ Suggested: http://www.bbc.co.uk/dna/h2g2/alabaster/A1019666 Suggested: Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou (on reserves at the library) Assignment: Based on the readings, answer the following questions. As always, use a separate piece of paper and type your answers using complete sentences and incorporating the question into your answer. Questions for Murphy, Working the Spirit chapter 2: 1) How does Murphy define vodou? How does this compare with popular stereotypes about vodou common in the US? 2) What is the meaning and significance of the concept of ―nation‖ in vodou? 3) How are vodou communities organized (i.e. what are the different religious positions within the community)? 4) What is ―head washing‖? What is the significance of the head in vodou? Why must the head be prepared? 5) What is the meaning and significance of the potomitan? 6) What is the role of dance in vodou? 7) On page 38, Murphy writes: ―to understand the spirit of vodou, then, is to see that it is an orientation to historical memory and to a living reality.‖ In your own understanding, what does this mean? Provide some concrete examples to support your answer. Questions for ―The Lwa‖ (p109-117): 1) Which of the lwas discussed in this section is most appealing to you and why? IN CLASS FILM: Legacy of the Spirit Outside Homework: See Resources area of Oncourse 10 October 13 Divine Horsemen Reading: *Deren, ―White Darkness‖ (247-262) Suggested: Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou (on reserves at the library) Outside Homework: See Resources area of Oncourse October 15 Bocors and Black Magic Reading: *Rodman, ―Vaudun’s Darker Side‖ (79-92) Assignment: Based on the readings, answer the following questions. As always, use a separate piece of paper and type your answers using complete sentences and incorporating the question into your answer. 1) What is the difference between the houngan (oungan) and the bocor? 2) What is black magic according to this author? October 20 Power Objects Reading: *MacAlister, ―A Sorcerer’s Bottle‖ (305-321) Suggested: *Brown, ―Making Wanga‖ (173-192) Assignment: Find or make a power object and bring it to class for discussion (more instructions on the Assignment page of Oncourse). October 22 In Search of the Zombi Reading: Davis, The Serpent and the Rainbow, chapters 1-6 Assignment: 1) Why do you think Davis begins his narrative about Haitian zombies with his adventures in the Amazon? Why does he name the first chapter ―The Jaguar‖? What is the significance of the jaguar to Davis? 2) What is Davis’ initial hypothesis about the zombi phenomenon? 3) How does his meeting with Lamarque Douyon (57-63) change Davis’ understanding of the zombi phenomenon? 4) On page 84, Davis says: ―…suddenly I understood and felt terribly foolish. I had been asking for a poison, but what I called a poison they called a trap or coup poudre. For them what created a zombi was not a drug but a magical act.‖ What does this mean? How does this realization change Davis’ understanding of the zombi phenomenon? 5) What is the lesson of the lime (p101)? October 27 Zombi as a Cultural Phenomenon Reading: Davis, The Serpent and the Rainbow, chapters 8; 10-13 + Epilogue Assignment: 1) Do the circumstances under which Ti Femme and Clairvius Narcisse were turned into zombis have anything in common? If so, what? 2) What is ―voodoo death‖? 3) Why, according to Davis, is scientific thinking the opposite of vodou? 4) Name and briefly describe the basic components of humans in the vodou conception. 5) What is the vodou notion of illness and health and how is this related to the spirit world? 6) What does Davis conclude about how a Zombie is made? What is the role of the powder in this process? What is the role of the ti bon ange? Outside Homework: See Resources area of Oncourse 11 October 29 Reading: Zombie as Symbol *Hurston, ―Zombies‖ (179-198); and *Gaiman, ―Bitter Grounds‖ (283-304) Assignment: 1) Based on the Hurston reading what is the Haitian understanding of the Zombie? What are the main characteristics of Haitian Zombies? What kinds of activities are associated with Zombies? 2) If we consider the zombie as both a legendary figure (like the Vampire, Sasquatch, or fairies, ogres, etc.) and also as a symbol of a particular people’s history and fears, what do you think that the Zombie might symbolically express for Haitians--for example, what might the idea of a soulless laborer who toils endlessly for the benefit of another mean in the context of Haitian history? 3) How is the Zombie of American movies different from the Haitian idea of the Zombie? 4) Notice the opening line of Neil Gaiman’s story ―Bitter Grounds.‖ In the course of the story, Gaiman uses the Haitian figure of the Zombie to explore the phenomenon of ―the living dead‖ in a contemporary, American context. What do you make of the story’s ending? Why is the main character unable to taste anything? What do you think is the significance of the bitter coffee that recurs throughout the story? Outside Homework: See Resources area of Oncourse November 3 NO CLASS November 5 Santería Reading: Murphy, Working the Spirit, chapter 4 Guest Lecture: Dr. Angela Castañeda November 10 Healing and the Botanica Reading: *Murphy, ―Botanica‖ (39-48) November 12 Santería Altars and Rituals Reading: *Brown, ―Thrones of the Orichas‖ Assignment: Using full sentences, please type your answers incorporating the question into your answer. Note: the religion of Santería is often called La Regla de Lucumí or simply Lucumí (Lucumí was the word for the Yoruba peoples used in Cuba). 1) What is the purpose of these thrones? On what specific occasions are thrones built and why? 2) The author argues that the thrones, implements, and traditions associated with Santería in Cuba are unique, New World creations that synthesize elements from different traditions. Using a specific example, discuss the African and European influences of your chosen example. 3) One aspect that all Afro-diasporan religions have in common is the centrality of the body. What is the significance of the body in Santería? How is it prepared and adorned to manifest a particular oricha? 4) What similarities do you find between Santería and Vodou? 5) Where religions of the book explain their theologies—their conceptions of the universe and sacred powers—in textual form, Afro-diasporan religions express their theologies in ritual and material objects. Based on this reading, what are some of the theological ideas expressed in Santería? Discuss a specific example. Outside Homework: See Resources area of Oncourse 12 November 17 Afro-Brazilian Religions: Candomblé Reading: Murphy, Working the Spirit, chapter 3 Outside Homework: See Resources area of Oncourse November 19 Afro-Brazilian Religions: Umbanda Reading: *Hayes, ―Umbanda‖ (1-19) IN CLASS FILM: Hail Umbanda November 24 Pomba Gira Reading: *Hayes, ―Wicked Women and Femmes Fatales‖ (1-28) November 26 - 30 THANKSGIVING BREAK December 1 Final Projects December 3 Final Projects December 8 NO CLASS: Enjoy the holidays 13