Classic Canon vs Fan Favorites

advertisement

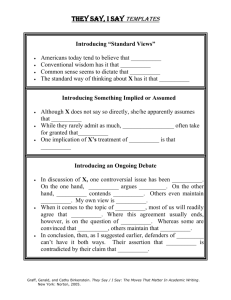

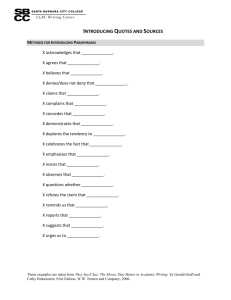

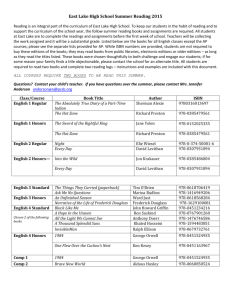

Buckman 1 Jaclyn Buckman Classic Canon versus Fan Favorites English doctor and writer Dr. John Aikin once said, “To choose a good book, look in an inquisitor’s prohibited list.” Every single year, decade, and century in movies, television, music, and literature, opposing lists of the top ranking of the aforementioned mediums are brought up. On the one side, there are those consisting of works by famous authors, award winning works, and those that broke the boundaries of a particular time as well as those they find simply offensive and foul, often referred to as banned books. On the other side of the critics’ choices, there are the works regarded as popular. These works of movies, books, and music may not win any award or break any unusual boundaries or social taboos, but they manage to capture the attention and hearts of the public sphere. However as Dr. Aikin stated, those on the aforementioned banned books lists often become quite popular with the public. This schism between the critically acclaimed and the fan favorites is clearly demonstrated within the realm of literature by the means of the difference between the literary canon and the best-sellers. Though the books residing on each of these particular lists often overlap, they never seem to match. This is shown to be true with the Modern Library’s lists of the Best 100 Novels for critics and readers (Random House, Inc.). Often readers feel torn and feel the need to choose between the classics and time-honored classics of the traditional literary canon and popular novels and other pieces of literature that tug at their heart strings. It is this dilemma that Dr. Janice Radway struggled with in her own literary past. In the introduction of her book A Feeling for Books, Radway seems to suggest that there should be no difference or separation between what is revered and what is loved in the world of literature. Radway would most likely suggest that both lists are essential in the world of literature while author Gerald Graff, though possessing a love for certain classical Buckman 2 canonical works, would seem to sway more towards the side of those classic canonical works because they required conscious thought and analysis whilst reading them. He would also prefer a schism and debate between the lists. He believed it to be essential because it created criticism and debate. These authors and their personal arguments pertaining to the literary canon give great insight into how and what is read in society as well as what is drawn from both. The top five books residing on Modern Library’s Top 100 Novels, according to their panel of critics and scholars, are as followed: Ulysses by James Joyce, The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man by James Joyce, Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov, and Brave New World by Aldous Huxley (Random House, Inc.). These books often appear upon other lists of traditional canonical works, and as a youth and even as a college student, Gerald Graff had more than likely had some exposure or encounter with at least some of them. More than likely, he also disliked these initial encounters, even those popular novels of the time. As a youth, Graff abhorred the idea of reading and books, tossing away even the popular novels of the time (Graff 42). It was not until college that Graff began to appreciate literature when he learned about the criticism surrounding Mark Twain’s famous novel The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. This made him begin to love literature and the books he was being exposed, a fact that he said came a little too late. According to Graff, “It was through exposure to such critical reading and discussion over a period of time that I came to catch the literary bug, eventually choosing the vocation of teaching. This was not the way it is supposed to happen. In the standard story of academic vocation that we like to tell ourselves, the germ is first planted by an early experience of literature itself (Graff 44).” Buckman 3 Graff believed that the practice of simply letting the essence of these canonical works teach those who may read them was an improper one, and that if it were possible to gain a love of books from this method, there would be no need to hold classes regarding them (Graff 45). With regards to the canon presented by Modern Library, Graff would advocate them above what is simply popular because of the cultural impact and also because of the various criticisms surrounding them. Graff would most certainly have disregarded or at least disagreed with the reader’s choices of the top 100 novels. On top of this particular list, there is the futuristic novel Atlas Shurgged by Ayn Rand. Though some of the novels overlap between both lists, many novels solely appear on either on list or the other (Random House, Inc.). Popular literature, those bestsellers and blockbusters, often requires little to no deep thought or criticism. These are the books that are just read for the sake of reading and let the texts speak and convey their own meaning organically. They do not lend themselves to critical discussion, something Graff held in high regard because of his belief that such critical thought was essential in literature and learning (Graff 44). Graff felt as though through criticism of literature, real knowledge and information could be gained. Therefore books from the Readers’ Choice such as The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams and The Hunt for Red October by Tom Clancy simply could not give Graff any real value to read (Random House, Inc.). However, Graff would not toss out those that have appeared on banned books list because they allowed for critical thought and discussion. This is shown to be true when he discusses his discovery of his love of reading while discussing Mark Twain’s The Adventure of Huckleberry Finn (Graff 42). Those pieces of literature, Graff would believe, would warrant being on those top lists. Buckman 4 Radway too would show support and admiration for the critics’ choices of the top 100 novels. On the other hand, she would also equally support the readers’ choices of the top 100 novels because she found love in those “middlebrow” books. In the introduction to her book A Feeling for Books, Radway discusses the difficulty of reconciling her respect of the canonical works of literature and those that appeared in her Book-of-the-Month Club which she joined in 1975 (199). Originally subscribing to the book club which she found to be frivolous and middlebrow in their choices of book selections simply in order to afford the Oxford English Dictionary which many of her professors and peers possessed, she eventually went on the purchase a countless number of a variety of books from the Book-of-the-Month Club, including those that could have easily appeared on the readers’ choice list by the Modern Library which she began to love (200). Initially, Radway felt ashamed of this growing love for the popular, yet not critically acclaimed works of literature found in catalogue and tried to limit herself to those canonical, stating, “I could not always discipline my preferences as I thought I should. I still liked the books I read at night a lot more than the books I loved for class (201).” As time went on and as she went on her literary journey, Radway began to notice that the schism and differences between what critics may regard as good literature and what readers would choose for their top choices was not as black and white or clear cut as she may have once thought some time ago. She found several similarities between those editors from the Book-ofthe-Month Club and her professors from her college years in regards to their beliefs and practices (Radway 206). Throughout the meetings held with the aforementioned editors of the club, she learned that they held similar beliefs on what should and should not appear on their list of books. However, they seemed to believe that several of the traditional canonical works of literature were too highbrow for their readers and customers (Radway 206). She deduced a quite accurate idea Buckman 5 of what the actual difference between the critics’ choices and the readers’ choices of what good literature is: while canonical works teach and are of a higher intellect, works chosen and loved by the readers represent their lives and their cultures which makes them easily accessable to those who may read them (Radway 208). Radway, if asked or questioned about the lists of the Modern Library’s Top 100 Novels, would state that both lists hold great importance in society and brilliantly demonstrates both high and middle culture. There is absolutely no true and definite literary canon. There cannot be one whilst there are differing opinions on what is regarded as truly good literature, which is not likely to ever happen. Never in history has there been an absolute and unanimous decision on what should be included in the scholarly literary canon as authors and their works are constantly added and dropped from the lists. Therefore, any list created naming what is good and what is not in terms of literature, is subjective and not entirely accurate. What tends to happen is that sometimes the critics and readers agree and sometimes they do not, and this is seen on the lists of best novels. There are also often quarrels amongst the groups of critics and the groups of readers. Judging by the lists as well as the critics Gerald Graff and Janice Radway’s differing arguments on what should be read, one can see both why the Modern Library’s lists differ at points and why a true literary canon cannot exist. By looking through the eyes of Radway and Graff, a reader can draw both knowledge and enjoyment from whatever piece of literature may cross their paths. Buckman 6 Works Cited Graff, Gerald. "Disliking Books at an Early Age." Richter, David H. Falling into Theory. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2000. 41-48.Print. Radway, Janice A. "Introduction to A Feeling for Books." Richter, David H. Falling into Theory. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2000. 199-211.Print. Random House, Inc. 100 Best Novels. October 20 1998. 8 March 2011.Web.