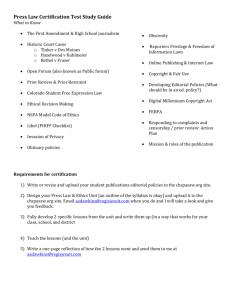

“If You Want to Speak Spanish, Go Back to Mexico”?: A First

advertisement