Medical Screening and Evacuation

advertisement

[

RESIDENT’S CASE PROBLEM

]

MICHAEL S. CROWELL, PT, DPT¹DEHC7DM$=?BB" PT, DSC, OCS, FAAOMPT²

Medical Screening and Evacuation:

Cauda Equina Syndrome in a Combat Zone

ow back pain (LBP) is a prevalent condition, particularly in

primary care clinics, with billions of dollars spent each year

on treatment.33 It is the fifth most common reason for all

physician visits in the United States.11 Approximately 25% of

adults report LBP lasting at least 1 day within the past 3 months,11

with approximately 14% having an episode that lasts longer than 2

weeks.15 Prevalence ranges from 15% to 20% over a single year40

and approximately 70% over the course of a person’s lifetime.15,27,30,40

L

The majority of patients (85%)

with LBP have conditions that cannot

be reliably attributed to a specific disTIJK:O:;I?=D0 Resident’s case problem.

T879A=HEKD:0 Cauda equina syndrome (CES)

is a rare, potentially devastating, disorder and is

considered a true neurologic emergency. CES often

has a rapid clinical progression, making timely recognition and immediate surgical referral essential.

T:?7=DEI?I0 A 32-year-old male presented to a

medical aid station in Iraq with a history of 4 weeks

of insidious onset and recent worsening of low back,

left buttock, and posterior left thigh pain. He denied

symptoms distal to the knee, paresthesias, saddle

anesthesia, or bowel and bladder function changes.

At the initial examination, the patient was neurologically intact throughout all lumbosacral levels

with negative straight-leg raises. He also presented

with severely limited lumbar flexion active range of

motion, and reduction of symptoms occurred with

repeated lumbar extension. At the follow-up visit, 10

days later, he reported a new, sudden onset of saddle

anesthesia, constipation, and urinary hesitancy,

with physical exam findings of right plantar flexion

ease or spinal abnormality.11,15 Current

recommendations suggest classifying

patients into 3 broad categories: nonspeweakness, absent right ankle reflex, and decreased

anal sphincter tone. No advanced medical imaging

capabilities were available locally. Due to suspected

CES, the patient was medically evacuated to a neurosurgeon and within 48 hours underwent an emergent

L4-5 laminectomy/decompression. He returned to full

military duty 18 weeks after surgery without back or

lower extremity symptoms or neurological deficit.

T:?I9KII?ED0 This case demonstrates the importance of continual medical screening for physical therapists throughout the patient management

cycle. It further demonstrates the importance of

immediate referral to surgical specialists when

CES is suspected, as rapid intervention offers the

best prognosis for recovery.

TB;L;BE<;L?:;D9;0 Differential diagnosis,

level 4. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2009;39(7):541549. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2009.2999

TA;OMEH:I0 direct access, lumbar spine, low

back pain, red flags, spinal cord

cific LBP, nerve root syndrome (radiculopathy or stenosis), and serious spinal

pathology.11,30

LBP secondary to nerve root syndrome, although less common, is a potentially disabling condition.23 Nerve

root syndrome may be related to radiculopathy, spinal stenosis, or cauda equina

syndrome (CES).23 Due to the potential

for poor prognosis, timely recognition of

neurologic involvement is essential for

optimal patient outcomes.23

Acute lumbar disc herniation is one

potential source of both radiculopathy

and CES. Approximately 90% of cases of

sciatica are caused by a herniated disc.29

Overall incidence of symptomatic disc

herniation is 1% to 2%,29,39 for which

200 000 discectomies are performed annually.39 Peak incidence of this disorder is

between the ages of 30 to 55 years.15

Characteristics of acute disc herniation include abrupt, intense onset of

pain that is increased by bending or lifting.48 The most common levels of symptomatic herniation are L5-S1 and L4-5,

which comprise approximately 90% to

98% of cases11,15 and correspond to the

spinal levels that receive the majority of

compressive forces in the lumbar spine.

Clinically, disc herniation at these levels

frequently manifests as L5 and S1 nerve

root compression disorders characterized by radiating pain below the knee,

1

Brigade Combat Team Physical Therapist, Iraq. 2 Program Director and Associate Professor, US Army-Baylor University Postprofessional Doctoral Program in Orthopedic Manual

Physical Therapy, Brooke Army Medical Center, Fort Sam Houston, TX. This case was seen at a Troop Medical Clinic in Iraq. The opinions or assertions contained herein are the

private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or reflecting the views of the United States Army or Department of Defense. Address correspondence to CPT

Michael Crowell, 235 Lancaster Way, Richmond Hill, GA 31324. E-mail: michael.crowell2@us.army.mil

journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy | volume 39 | number 7 | july 2009 | 541

[

RESIDENT’S CASE PROBLEM

]

:?7=DEI?I

TABLE 1

Red Flags

History of Present Illness

T

Unrelenting night pain

History of cancer or recent infection

Unexplained weight loss or gain

Recent trauma

Difficulty with micturation*

Loss of anal sphincter tone or fecal incontinence*

Saddle anesthesia*

Gait disturbance*

* Indicates elements specific to cauda equina syndrome.

decreased sensation in a dermatomal

pattern, myotomal weakness, reflex

changes, and positive straight-leg raise

tests.11,15 However, examination of patients with acute disc herniation should

always include careful screening for serious pathology, both before initiation

of and during ongoing conservative

interventions. 3,11 Red flag differential

diagnoses may include CES, metastatic

spinal disease, spinal infection, epidural hematoma, and spinal fracture

or dislocation. 3 Screening for red flag

conditions should include questions

regarding bowel and bladder function

changes, sensory function changes in

the perianal region and genitals, unexplained weight loss or gain, fever, night

pain, history of cancer or infection,

history of trauma, and any gait disturbances (TABLE 1). 3,22

In adults, the spinal cord is approximately 42 to 45 cm in length and terminates at the lower border of the first

lumbar vertebra or upper border of the

second lumbar vertebra at the conus medullaris.20 The spinal cord is ensheathed by

3 protective membranes from outward to

within: the dura mater, arachnoid, and

pia mater.20 These membranes extend

to the first segment of the coccyx as the

filum terminale.20 The outer layer of the

dura, arachnoid, and the subarachnoid

cavity is termed the thecal sac, which is

filled with cerebrospinal fluid.20

The term cauda equina describes the

lumbar and sacral spinal nerves descending from the conus medullaris. During

embryo development, the spinal cord and

vertebral column have relatively unequal

rates of growth.20 As a result, the lumbar

and sacral spinal nerves descend almost

vertically to reach their points of exit.20

This configuration resembles a “horse’s

tail,” from which the term cauda equina

is derived in Latin.

CES is a rare, potentially devastating

disorder that may arise from an acute

disc herniation and is considered a true

neurologic emergency.8,45,48 The estimated

prevalence of CES is 0.04% of all patients

presenting with a primary complaint of

LBP,11,15,45 and it is most prevalent in the

fourth or fifth decade of age.43,45 CES occurs in 1% to 2% of all lumbar disc herniations that progress to surgery.1,8,15,43,44

CES is most frequently associated with

a nontraumatic massive midline posterior disc herniation, commonly located at

L4-5, followed by L5-S1 and L3-4.43,44,45,48

The sacral nerves, which lie medially in

the cauda equina, are affected disproportionately in this disorder. A clear diagnosis or a high index of suspicion for CES

should prompt immediate referral to a

surgical specialist. Referral to an orthopaedic spine surgeon or neurosurgeon,

where available, is the most direct route

of referral; otherwise, the patient should

be sent to an emergency department.

The purpose of this resident’s case

problem is to describe the evaluation,

treatment, referral, and outcomes of a

patient exhibiting signs and symptoms

of CES evaluated by a physical therapist

in a direct-access environment.

he patient was a 32-year-old

Caucasian male (height, 1.83 m;

body mass, 77.1 kg; body mass index, 23.1 kg/m2) who initially presented

to a physical therapist in a combat zone

with a chief complaint of insidious onset

low back and left posterior thigh pain. He

was deployed for combat with a primary

responsibility of training foreign military

officers. During convoy operations, he was

a machine gunner, standing in the turret

at the top of an armored vehicle. This job

required prolonged periods of wearing

protective equipment weighing in excess of 36 kg, often for periods exceeding 8 hours. His symptoms were located

in the lower lumbar spine (left greater

than right), left buttock, and left posterior thigh, as shown in <?=KH;'. The total

duration of symptoms was approximately

4 weeks, but the patient reported a significant increase in intensity of pain the

day prior to evaluation without any specific trauma. He described a dull, aching

pain, and a pain that was intermittently

sharp. The patient denied numbness or

tingling in any location or pain below the

level of the knee. Baseline numeric pain

rating scale (NPRS),25 where 0 is no pain

and 10 is the worst pain that the patient

could imagine, was 4/10 at rest and 7/10

at worst. The patient noted increased

pain with running and forward flexion of

the lumbar spine. Rest and lying supine

relieved his symptoms. His past medical

history was significant for 3 to 4 prior occurrences of LBP over the past 8 years,

with similar presentation that, he stated,

resolved without treatment. The patient

had no history of spine or extremity surgery. No previous imaging studies had

been performed. His stated goal was to

decrease his overall pain level during performance of his military duties.

Systems Review

The patient denied saddle anesthesia,

bowel or bladder function changes, unexplained weight loss or gain, night pain, or

542 | july 2009 | volume 39 | number 7 | journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy

Assessment, Intervention,

and Re-evaluation

<?=KH;'$Body chart of symptoms at initial presentation through day 9.

recent trauma, and had no history of cancer

or infection. In screening for nonmusculoskeletal pathology, the patient reported no

history of cancer, cardiovascular, or pulmonary disease, and no recent occurrence

of nausea, vomiting, fever, changes in appetite, difficulty swallowing, shortness of

breath, dizziness, or changes in balance.

Test and Measures

The patient was neurologically intact

bilaterally with 5/5 strength as assessed

with manual muscle testing26 throughout the L2 to S1 myotomes, sensation

was intact to light touch throughout the

L2 to S1 dermatomes, and knee jerk and

ankle jerk muscle stretch reflexes were

2+ (normal). Babinski reflex testing was

negative. He presented with decreased

lumbar lordosis and a guarded, obviously

painful, movement of the spine. The patient displayed a left-sided antalgic gait,

with decreased left hip extension and

early termination of the stance phase of

the gait cycle. Active range of motion was

severely limited in lumbosacral flexion,

with the ability to reach only the midanterior thigh region with the fingertips,

and moderate to severe pain in the low

back, left buttock, and left posterior thigh

at the end range of motion. Lumbosacral

extension and side bending were within

normal limits, without an increase in

pain from his baseline NPRS. Repeatedmotion testing was performed as described by McKenzie.35 Ten repetitions

of flexion in standing increased his back,

buttock, and posterior thigh pain, while

10 repetitions of extension in standing

reduced those symptoms. Straight-leg

raise tests did not produce radicular pain

but caused a severe increase in LBP at 15°

of hip flexion on the right and 45° of hip

flexion on the left. Hip flexion range of

motion during single knee to chest was

within normal limits bilaterally, with increased LBP that was approximately 50%

less than with straight-leg raise testing.

A lumbar quadrant test was negative bilaterally. Passive vertebral motion testing,

as described by Maitland,34 produced local pain at L3, L4, and L5 with central

passive posterior-anterior accessory intervertebral motion (PAIVM). Unilateral

PAIVM testing produced local pain at

L3-4, L4-5, and L5-S1, equal bilaterally.

No referral of pain was noted with passive accessory movement assessment.

Using a treatment-based classification

approach,6,7,18 the patient was classified

into the specific exercise classification

and prescribed extension-oriented exercises. Either standing or prone repeated

extension exercises were to be performed

every 2 waking hours, with 10 repetitions,

holding each repetition 2 to 3 seconds at

end range. Education consisted of avoidance of sitting for greater than 20 to 30

minutes, avoidance of full end-range

flexion positions, and the use of a lumbar

roll while sitting and wearing protective

equipment. The treating physical therapist, who had privileges for prescribing

nonnarcotic medication,5 prescribed 7.5

mg Meloxicam (Mobic, 2 tablets once

daily) and 500 mg acetaminophen (Tylenol, 2 tablets every 4-6 hours, as needed)

for pain relief during performance of his

military duties. Because this patient was

essential to the success of his unit’s mission, only a home exercise program was

prescribed, and a follow-up was scheduled for 2 weeks later. He was instructed

to return to the clinic at an earlier time

for re-evaluation if symptoms worsened.

The patient presented for follow-up on

day 4 (3 days after the initial evaluation)

with a complaint of increased pain unrelieved by positioning and only short-term

relief with the home exercise program.

His baseline NPRS at rest had increased

to 6/10. He reported a decreased NPRS

to 4/10 after performing home exercises,

but he would return to baseline after approximately 30 to 60 minutes. Since the

initial evaluation, he had continued to

perform all of his duties, including extended wear of protective equipment.

The physical examination, including the

neurological examination, did not differ

from the initial evaluation, with the exception of increased pain with all testing.

His case was discussed with a physician

and he was prescribed a narcotic pain

medication for use as needed, re-educated in the home exercises to ensure proper

performance, and instructed to continue

the home exercises as tolerated. The pa-

journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy | volume 39 | number 7 | july 2009 | 543

[

RESIDENT’S CASE PROBLEM

tient was to follow-up within 1 week to

monitor the stability of his symptoms and

assess his response to the modified treatment plan.

At a second follow-up 3 days later (day

7 after initial exam), the patient continued to have significant pain. He was able

to perform his duties, but the sharp pain

was becoming more frequent and intense. He also reported a recent onset

of numbness in his left posterior thigh.

He continued to deny any radiating pain

below the knee or right-sided symptoms.

The physical exam was unchanged from

initial evaluation and a neurological assessment continued to reveal no motor, sensory, or reflex deficits bilaterally.

Although strength of left ankle plantar

flexion was 3+/5, he was limited by pain

secondary to a recent ankle inversion

sprain on rocky, uneven terrain, which

he described as unrelated to his low back

symptoms and had occurred between the

first and second re-evaluation.

Due to increasing pain despite conservative therapy and medications, he was

restricted from missions that required the

wear of his protective gear and from any

lifting, bending, or twisting. Daily physical therapy intervention in the clinic was

initiated at that time. The therapist chose

to continue with a supervised exercise

program and adjunct pain-relieving modalities, because the high-load demands

of this patient’s work duties up to that

point made accurate assessment of the

patient’s response to treatment difficult.

Intervention consisted of interferential

electrical stimulation with 4 pads bracketing the symptomatic area of the lumbar

spine, the patient positioned in prone,

and the intensity at the patient’s level of

tolerance. Treatment was combined with

moist heat for 20 minutes, followed by

supervised extension exercises and left

lumbar rotation stretches, both of which

provided mild relief of the lower extremity pain. Lumbar extension exercises consisted of 3 sets of 10 repetitions, with a

2- to 3-second hold at end range, without

manual overpressure. Lumbar left rotation stretching consisted of 30-second

]

<?=KH;($Body chart of symptoms at 10-day follow-up.

holds, with 3 repetitions. The patient’s

home exercise program remained unchanged from the initial evaluation.

Upon presenting for his third day of

in-clinic treatment (10 days after initial

evaluation), the patient had a new complaint of numbness and tingling in the

saddle region and a change in bowel and

bladder function. Although he denied any

incontinence, he stated that it was difficult to control initiation and cessation

of urination and bowel movements. The

patient also described new symptoms

in the right lower extremity (previously

asymptomatic), with an inability to rise

up onto his toes and constant tingling in

the right calf, while his left lower extremity symptoms were unchanged from the

last evaluation. <?=KH;( shows the body

chart associated with the new symptom

presentation. He stated, however, that his

pain level had decreased to 4/10 at rest

and 5/10 at worst since he stopped wearing his protective gear 2 days prior.

A detailed physical examination was

performed, with an orthopaedic physician assistant on staff providing further

guidance on neurological assessment of

the S3-4 levels. Lumbar spine range of

motion was unchanged from the initial

evaluation. A straight-leg raise test bilaterally continued to provoke symptoms

only in the low back region. No sensory

deficiencies to light touch or sharp-dull

stimuli were noted throughout the lower

extremities bilaterally, including the L4S1 dermatomes. Strength was reduced in

right ankle plantar flexion to 3–/5. The

right ankle jerk (S1) reflex was absent. A

rectal examination revealed decreased

anal sphincter tone and an absent anal

wink reflex. The cremasteric reflex was

intact. The Babinski reflex was normal.

Gait was severely impaired with a decreased step length bilaterally and impaired toe-off present on the right.

Referral

Because of his rapidly progressive neurological symptoms and a suspicion of

cauda equina compression, the physical therapist scheduled the patient for

medical evacuation and referral to a

neurosurgeon. No advanced imaging was

performed, as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography

(CT) scan capabilities were not available

at the local facility. Evacuation to neurosurgery care and advanced medical imaging occurred within 48 hours.

544 | july 2009 | volume 39 | number 7 | journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy

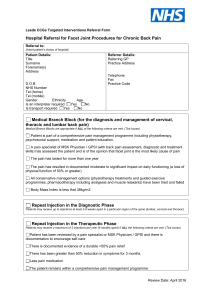

J78B;(

Radiology Impression of Computed Tomography

(CT) Scan Prior to Surgical Intervention

L1-2: No disk bulge, central canal, or neuroforaminal stenosis

L2-3: No disk bulge, central canal, or neuroforaminal stenosis

L3-4: Broad-based disk bulge with no sadistic and central canal or neural foraminal stenosis

L4-5: Moderate disk space narrowing; degenerative changes of the inferior endplate of L4; large disk protrusion with

moderate central canal stenosis, difficult to tell, but likely some extruded fragments posterior to L5; moderate to

severe lateral recess stenosis bilaterally; exiting nerve roots in the neural foramina appear relatively normal

L5-S1: No significant disk bulge, central canal, or neural frontal stenosis

D[kheikh]_YWbWdZ?cc[Z_Wj[

Postoperative Care

Upon arrival at a Combat Support Hospital, the patient was evaluated by a military neurosurgeon. Physical examination

findings were consistent with those at the

medical aid station. Additionally, bladder

function was evaluated and the patient

was found to have a postvoid residual

of 300 cc. Although MRI is the recommended imaging modality for CES, because of the detail provided to the soft

tissues and spinal canal,11 it was not available in that location either. Instead, a CT

of the lumbar spine with contrast, an alternate recommendation to image CES,11

was performed. The findings reported by

the radiologist were suggestive of underlying pathology that could be clinically

correlated with CES (J78B;().

Following neurosurgical evaluation,

he was prepped for immediate surgical intervention. A L4-5 laminectomy

and decompression was performed and

a large extruded disc fragment was removed from the epidural space. The next

day the patient was evacuated to Landstuhl Regional Medical Center in Germany for inpatient recovery. Three days

postsurgery, he was evaluated by a physical therapist. He had an NPRS of 2/10,

continued complaints of bowel and bladder dysfunction, and continued right calf

weakness. He was independent in bed

mobility, edge-of-bed activities, and sitto-stand transfers. Right ankle plantar

flexion was 3+/5, but the patient was able

to independently ambulate approximately

18 m. The patient was instructed in ankle

pumps along with progressive ambulation to prevent deep venous thrombosis2,9

and, to enhance functional recovery, with

lower extremity exercises aimed to maintain nervous tissue mobility to prevent

postoperative nerve root scarring. After

3 days in Germany, the patient was then

evacuated to his final destination, Brooke

Army Medical Center, Fort Sam Houston,

TX, for follow-up neurosurgical care and

recovery.

H[Yel[hoWdZEkjYec[

The patient arrived at Brooke Army Medical Center 6 days after surgery. An MRI

performed on admission demonstrated

normal postoperative changes and no

residual disc herniation. During his first

neurosurgery postoperative evaluation,

he presented with right buttock pain,

resolving saddle paresthesia, numbness

of the right lateral foot region and toes,

bladder incontinence, and erectile dysfunction. Ankle and knee muscle stretch

reflexes on the right were hypoactive, but

he had 5/5 strength throughout both lower extremities. Within 1 week he returned

to neurosurgery with some residual right

buttock and foot symptoms, resolved saddle paresthesia, and normal reflexes. He

was cleared by the surgeon for medical

convalescent leave for 30 days, with an

intended referral to a physical therapist

upon return. Upon return from convalescent leave (approximately 6 weeks after

surgery), he had regained full sensory

function and continued to demonstrate

normal motor function. No referral was

made to physical therapy, and the patient

was cleared by the surgeon to progress his

walking distance as tolerated and start

stationary bike exercising. By 12 weeks,

the patient had self-progressed to walk-

ing 1.6 km daily, doing pool exercises at

home, and using 1- to 2-kg weights for

upper extremity exercises. At 4-month

follow-up he had no residual neurological

or functional deficits and reported a current walking program with a 5-kg backpack. He was cleared by neurosurgery for

full return to military duties, including

redeployment.

:?I9KII?ED

T

his resident’s case problem describes what could be considered a

classic presentation of CES, recognized by a physical therapist practicing

in a direct-access setting. By a continual

medical-screening process over multiple

visits, the therapist recognized an atypical progression of mechanical LBP, which

then acutely manifested itself as CES.

Early recognition, confirmation, referral,

and surgical intervention were associated

with a good outcome, consistent with literature that suggests a good prognosis

with early detection and treatment.1,43,44

C[Y^Wd_YWbB8F

The patient in this case initially presented with a history and physical examination findings consistent with nonspecific

mechanical LBP and no red flag signs

or symptoms. Recent research supports

the use of a treatment-based classification approach for acute LBP of this nature.6,7,10,18,24 Due to centralization of his

symptoms with repeated movement in

extension, this patient was classified into

the specific exercise classification based

upon the first step in the algorithm described by Fritz et al.18 Browder et al7

examined the effectiveness of an extension-oriented treatment approach in a

subgroup of patients with LBP extending distal to the buttocks that centralized

with extension movements. In patients

meeting these criteria, treatment using

extension-oriented exercises resulted in

significantly greater reduction of pain

and disability than treatment using lumbar stabilization exercises. Additionally,

Long et al32 demonstrated that patients

journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy | volume 39 | number 7 | july 2009 | 545

[

RESIDENT’S CASE PROBLEM

with a movement directional preference

for symptom reduction (extension in this

case) significantly improved when performing specific exercises in that direction as opposed to general exercise, and

worsened performing exercises in the opposite direction.

compression. Although his finger-to-floor

distance was severely limited, this physical examination finding may also be associated with nonspecific LBP, which was

his initial classification.

The current case describes mechanical

LBP without initial evidence of nerve root

dysfunction, which rapidly progressed to

CES. A thorough evaluation is essential

for accurate identification of LBP with

nerve root syndrome and CES. The patient history should include any potential

mechanisms of injury, the location, description, nature, and intensity of pain,

the presence or absence of any sensory

abnormalities, aggravating factors, easing factors, and past medical history. The

physical examination should include a

neurologic screen, an assessment of lumbosacral range of motion, assessment of

passive vertebral motion, the straight-leg

raise test, tests for muscle flexibility, and

tests for sacroiliac dysfunction. Sensitivity, specificity, and likelihood ratios for

various physical examination and historical items with respect to nerve root

syndrome are listed in TABLE 3.

In general, information from the patient history is better for ruling out nerve

root syndromes and the physical examination is better for ruling in.50 Significant

indicators of nerve root syndrome include

focal muscle weakness and limited lumbar flexion, as indicated by a large fingerto-floor distance.23 Other predictors may

include lower extremity pain that is greater than back pain, a dermatomal pattern

of pain location, and increased pain with

coughing, sneezing, and straining.23

The patient in this case report did not

clearly fit into a nerve root classification

during the initial visits. He presented

with symptoms proximal to the knee,

and neurologic screening did not reveal

either motor loss, sensory impairment,

or diminished reflexes. Straight-leg raise

testing did not produce lower extremity symptoms consistent with nerve root

:_W]dei_ie\9;I

CES often has a rapid clinical progression

from other forms of LBP, which makes

timely diagnosis extremely important.

CES must be included in the differential

Diagnostic Test Properties for

Tests of Nerve Root Dysfunction

TABLE 3

D[hl[Heej:oi\kdYj_ed

]

I[di_j_l_jo

If[Y_ÓY_jo

!BH

ÅBH

Patient history

Presence of sciatica15

0.95

Lower extremity pain greater than back pain50

0.82

0.54

1.74

0.33

Dermatomal distribution of pain50

0.89

0.31

1.3

0.34

Physical examination

Paresis (weakness, not specific)50

0.27

0.93

4.11

0.78

Absent knee jerk or ankle jerk50

0.14

0.93

2.21

0.78

Finger-to-floor greater than 25 cm50

0.45

0.74

1.71

0.75

Straight-leg raise11,12,15,15,29*

0.91

0.26

1.23

0.35

Crossed straight-leg raise11,12,14,23,29†

0.29

0.88

2.42

0.81

Ankle dorsiflexion weakness15

0.35

0.7

1.17

0.93

0.71

Great toe extension weakness12,15,31

0.50-0.61

0.55-0.70

1.36-1.67

Impaired ankle jerk12,15,23,31

0.47-0.50

0.6-0.90

1.25-4.70

0.83

Ankle plantar flexion weakness15

0.47-0.60

0.76-0.95

1.96-12.0

0.42-0.70

Quadriceps weakness15

0.01-0.40

0.89-0.99

1.00-3.64

0.67-1.00

Abbreviations: +LR, positive likelihood ratio; –LR, negative likelihood ratio.

* Positive straight-leg raise defined as reproduction of radicular symptoms with elevation of the ipsilateral lower extremity between 30° and 70° of hip flexion.

†

Positive crossed straight-leg raise defined as reproduction of radicular symptoms with elevation of the

contralateral lower extremity between 30° and 70° of hip flexion.

TABLE 4

Differential Diagnosis of Low Back Pain (LBP)

With Potential Neurologic Involvement

HWZ_YkbefWj^o<hec

7Ykj[:_iY>[hd_Wj_ed

Spinal Stenosis

Cauda Equina Syndrome

Age (y)

30-55

60

40-60

History

Acute or recurrent episodes

Insidious onset of

chronic, progressive

LBP; more recent

onset of lower extremity symptoms

Insidious onset of severe LBP

with or without saddle

anesthesia, bowel/bladder

function changes, possible

history of chronic LBP

Pain pattern

Pain and/or numbness

radiating to 1 lower

extremity below the

knee, usually increased

with lumbar flexion

Lower extremity symptoms

increased with lumbar

extension, relieved by

lumbar flexion

Usually presents with radiating

pain and numbness/tingling

in both lower extremities,

increased with lumbar flexion

Neurological exam

Sensory and/or motor

changes, diminished/

absent deep tendon

reflexes unilaterally

Sensory and motor

changes

Bilateral sensory and/or motor

changes, diminished/absent

deep tendon reflexes, sensory

and motor changes at S3-4

levels

Range of motion

Guarded, limited

Pain and limited extension

Guarded, limited

Other tests

Straight-leg raise

Stage treadmill test

Straight-leg raise

546 | july 2009 | volume 39 | number 7 | journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy

diagnosis for patients presenting with

LBP with or without signs/symptoms of

nerve root compression,45 and the patient

history should include special questions

that attempt to identify patients with serious spinal pathology. TABLE 4 describes

common subjective and objective findings useful for the differential diagnosis

of possible neural involvement. Approximately 30% of patients present with

CES as the first manifestation of lumbar

disc herniation.1,44 More often, however,

patients will present with chronic LBP

that progresses rapidly to CES within 24

hours.43 Over a 10-day period of general

worsening but neurologic stability, the

patient in this case rapidly progressed

over 24 hours from a history without any

red flag symptoms to all of the red flags

associated with CES, including difficulty

with micturition, loss of anal sphincter

tone, saddle anesthesia, and severely impaired gait.

The physical examination to identify

CES must include assessment of the L1

to S3-4 levels, including anal sphincter

tone (S3-4), perianal sensation (S3-4),

the anal wink reflex (S3-4), and the cremasteric reflex (L1-2) (TABLE 5). The most

frequent physical exam finding is urinary

retention.11,15,23,45 A residual volume greater than 100 to 200 cc is considered positive for urinary retention.45 Decreased

anal sphincter tone is present in 60% to

80% of individuals with CES.15,45

Patients who present with severe or

progressive neurologic deficits should

have a prompt imaging work-up, with

MRI (preferred) or CT.11 While the advanced diagnostic imaging was delayed

in this case due to lack of availability, the

CT images demonstrating the patient’s

midline herniation at the L4-5 level were

consistent with the most common location and type of disc herniation associated with CES.11,15

Referral and Treatment of CES

The primary indicators for neurosurgical

referral for this patient were the presence

of bowel and bladder function changes,

saddle anesthesia, decreased anal sphinc-

Diagnostic Test Properties of

Tests for Cauda Equina Syndrome

TABLE 5

Urinary retention11,15,23,45

15,23

I[di_j_l_jo

If[Y_ÓY_jo

!BH

ÅBH

H[\[h[dY[i

0.9

0.95

18

0.01

Chou, Deyo, Haswell, Small

Unilateral or bilateral sciatica

0.80

Deyo, Haswell

Unilateral or bilateral motor/sensory deficits15,23

0.80

Deyo, Haswell

Positive straight-leg raise15,23*

0.80

Deyo, Haswell

Sensory deficit: buttocks, posterior-superior

thigh, perianal region3,15

0.75

Arce, Deyo

Abbreviations: +LR, positive likelihood ratio; –LR, negative likelihood ratio.

* Positive straight-leg raise defined as reproduction of radicular symptoms with elevation of the ipsilateral lower extremity between 30° and 70° of hip flexion.

ter tone, and progressive neurological

changes (new onset of significant motor

weakness in the S1 myotome).

CES is the primary absolute indication

for acute surgical treatment of lumbar

spine pathology.3 Rapid recognition coupled with timely referral and surgical care

provides the best chance of functional recovery.45 The treatment of choice is surgical decompression, usually a laminectomy

followed by discectomy.43,44 Performing

the laminectomy first allows excision of

the extruded disc material without undue

manipulation of the neural elements.43

The patient in this case had an emergent

laminectomy and decompression with removal of the extruded disc fragment from

the epidural space, confirming the diagnosis of CES. Surgical intervention was

performed within 72 hours of diagnosis,

which was extremely close to the length

of time where the risk of permanent neurologic deficit is increased. Although not

optimal, this delay was related to the realities of medical care in a combat environment, and every effort was made to

ensure a rapid evacuation of this patient

to a neurosurgeon. Even under standard

conditions, Shapiro44 previously reported

that only 45% of patients presenting to

the emergency room or primary care

physician underwent surgery within 48

hours.

Following surgery, the patient had limited inpatient physical therapy and was

later placed on a convalescent leave status

for 30 days. He was released with instructions to complete a progressive walking

program and given activity restrictions

consistent with discharge instructions for

patients receiving lumbar spine discectomy surgery. The patient was not referred

to outpatient physical therapy services as

part of his rehabilitation, possibly due to

his rapid symptom recovery, high level of

motivation to return to full function, and

ability to carefully progress on a general

home exercise program. Although this

patient did not receive postoperative outpatient physical therapy, there is strong

evidence to support intensive exercise

training beginning 4 to 6 weeks after

nonfusion lumbar spine surgery,13,16,37,42

which focuses on trunk/pelvis and lower

extremity strengthening,13,28,37 cardiovascular conditioning,41 and stretching of the

lumbopelvic musculature.41

Fhe]dei_ie\9;I

At his 18-week follow-up appointment,

the patient had an excellent result, with

no motor deficits, normal bowel and

bladder function, and return to full occupational duties. The excellent outcome

in this case highlights the importance of

early recognition of symptoms and immediate surgical referral.

Recent research has shown a significant advantage to treatment within 48

hours of onset.1,44 The risk of permanent

neurologic deficits is increased when

more than 72 hours elapses before definitive treatment1 and longer delays

correlate with worsening functional outcomes.8 In a meta-analysis of surgical

outcomes of CES, 3 factors suggestive

journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy | volume 39 | number 7 | july 2009 | 547

[

RESIDENT’S CASE PROBLEM

of a poor outcome were identified: history of chronic LBP, preoperative rectal

dysfunction (diminished motor or sensory function), and surgical intervention

greater than 48 hours after onset of CES.1

The patient in our case clearly recovered

better than expected, considering that all

3 of the items suggestive of a poor prognosis were present.

Attaching a numerical value to the

prognosis for patients with CES is difficult. A common problem in current research is the limited number of patients

studied, secondary to the rarity of the disorder. Subsequently, studies of CES often

have limited power to detect significant

differences in prognosis.1

F^oi_YWbJ^[hWfo:_h[Yj7YY[ii

During deployment in support of combat operations, military physical therapists provide direct access and primary

care for injured soldiers. The case of CES

presented here, however, is not necessarily unique to the military or combat

environment and a very similar presentation could be seen in any clinic with or

without direct access. Recent research

has shown that direct access to physical

therapy services does not compromise

patient safety. Physical therapists have

proven themselves able to identify serious

pathology that mimics a musculoskeletal

complaint4,17,19,21,36,38,49,51 and possess diagnostic accuracy equivalent to orthopaedic

surgeons.36,46

9ED9BKI?ED

P

hysical therapists must continually monitor patient status and

act appropriately when conditions

emerge that require immediate referral.

Physical therapists often treat a high volume of patients with LBP, the majority of

which are nonspecific and benign in nature. Although CES is a rare disorder, the

potential devastating consequences of a

missed diagnosis make a thorough evaluation and continuous medical screening

throughout the patient management

cycle essential. The current case problem

describes a unique episode of nonspecific

LBP with rapid progression to CES during

ongoing management, and correct diagnosis and referral by a physical therapist

in a direct-access setting. Timely referral

and surgical intervention in this case was

associated with an excellent outcome and

full functional recovery. T

13.

14.

H;<;H;D9;I

15.

1. Ahn UM, Ahn NU, Buchowski JM, Garrett ES,

Sieber AN, Kostuik JP. Cauda equina syndrome secondary to lumbar disc herniation:

a meta-analysis of surgical outcomes. Spine.

2000;25:1515-1522.

($ Aquila AM. Deep venous thrombosis. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2001;15:25-44.

3. Arce D, Sass P, Abul-Khoudoud H. Recognizing

spinal cord emergencies. Am Fam Physician.

2001;64:631-638.

4. Baxter RE, Moore JH. Diagnosis and treatment

of acute exertional rhabdomyolysis. J Orthop

Sports Phys Ther. 2003;33:104-108.

5. Benson CJ, Schreck RC, Underwood FB,

Greathouse DG. The role of Army physical

therapists as nonphysician health care providers who prescribe certain medications:

observations and experiences. Phys Ther.

1995;75:380-386.

6. Brennan GP, Fritz JM, Hunter SJ, Thackeray A,

Delitto A, Erhard RE. Identifying subgroups of

patients with acute/subacute “nonspecific” low

back pain: results of a randomized clinical trial.

Spine. 2006;31:623-631.

7. Browder DA, Childs JD, Cleland JA, Fritz JM.

Effectiveness of an extension-oriented treatment approach in a subgroup of subjects

with low back pain: a randomized clinical

trial. Phys Ther. 2007;87:1608-1618; discussion 1577-1609. http://dx.doi.org/10.2522/

ptj.20060297

8. Busse JW, Bhandari M, Schnittker JB, Reddy

K, Dunlop RB. Delayed presentation of cauda

equina syndrome secondary to lumbar disc herniation: functional outcomes and health-related

quality of life. CJEM. 2001;3:285-291.

9. Cayley WE, Jr. Preventing deep vein thrombosis

in hospital inpatients. BMJ. 2007;335:147-151.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39247.542477.AE

10. Childs JD, Fritz JM, Flynn TW, et al. A clinical

prediction rule to identify patients with low

back pain most likely to benefit from spinal manipulation: a validation study. Ann Intern Med.

2004;141:920-928.

11. Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, et al. Diagnosis

and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical

practice guideline from the American College of

Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann

Intern Med. 2007;147:478-491.

'($ Cleland J. Orthopedic Clinical Examination: An

16.

548 | july 2009 | volume 39 | number 7 | journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy

17.

18.

19.

(&$

('$

(($

()$

(*$

(+$

(,$

(-$

]

Evidence-Based Approach for Physical Therapists. Carlstadt, NJ: Icon Learning Systems;

2005.

Danielsen JM, Johnsen R, Kibsgaard SK, Hellevik E. Early aggressive exercise for postoperative rehabilitation after discectomy. Spine.

2000;25:1015-1020.

Deville WL, van der Windt DA, Dzaferagic

A, Bezemer PD, Bouter LM. The test of

Lasegue: systematic review of the accuracy in diagnosing herniated discs. Spine.

2000;25:1140-1147.

Deyo RA, Rainville J, Kent DL. What can the history and physical examination tell us about low

back pain? JAMA. 1992;268:760-765.

Filiz M, Cakmak A, Ozcan E. The effectiveness of

exercise programmes after lumbar disc surgery:

a randomized controlled study. Clin Rehabil.

2005;19:4-11.

Fink ML, Stoneman PD. Deep vein thrombosis

in an athletic military cadet. J Orthop Sports

Phys Ther. 2006;36:686-697. http://dx.doi.

org/10.2519/jospt.2006.2251

Fritz JM, Cleland JA, Childs JD. Subgrouping

patients with low back pain: evolution of a classification approach to physical therapy. J Orthop

Sports Phys Ther. 2007;37:290-302. http://

dx.doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2007.2498

Goss DL, Moore JH, Thomas DB, DeBerardino

TM. Identification of a fibular fracture in an

intercollegiate football player in a physical

therapy setting. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther.

2004;34:182-186. http://dx.doi.org/10.2519/

jospt.2004.1310

Gray H. Anatomy of the Human Body. 20th ed.

New York, NY: Bartleby; 2000.

Greathouse DG, Schreck RC, Benson CJ. The

United States Army physical therapy experience:

evaluation and treatment of patients with neuromusculoskeletal disorders. J Orthop Sports

Phys Ther. 1994;19:261-266.

Greene G. ‘Red Flags’: essential factors in

recognizing serious spinal pathology. Man Ther.

2001;6:253-255. http://dx.doi.org/10.1054/

math.2001.0423

Haswell K, Gilmour J, Moore B. Clinical decision rules for identification of low back pain

patients with neurologic involvement in primary

care. Spine. 2008;33:68-73. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815e3949

Hicks GE, Fritz JM, Delitto A, McGill SM. Preliminary development of a clinical prediction

rule for determining which patients with low

back pain will respond to a stabilization exercise

program. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:17531762.

Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM. What is

the maximum number of levels needed in pain

intensity measurement? Pain. 1994;58:387-392.

Kendall FP. Muscles: Testing and Function.

4th ed. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott, Williams

&Wilkins; 1993.

Kinkade S. Evaluation and treatment of acute

low back pain. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75:11811188.

(.$ Kjellby-Wendt G, Carlsson SG, Styf J. Results

of early active rehabilitation 5-7 years after

surgical treatment for lumbar disc herniation. J

Spinal Disord Tech. 2002;15:404-409.

(/$ Koes BW, van Tulder MW, Peul WC. Diagnosis and treatment of sciatica. BMJ.

2007;334:1313-1317. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/

bmj.39223.428495.BE

30. Koes BW, van Tulder MW, Thomas S. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain. BMJ.

2006;332:1430-1434. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/

bmj.332.7555.1430

31. Lauder TD, Dillingham TR, Andary M, et al.

Effect of history and exam in predicting electrodiagnostic outcome among patients with

suspected lumbosacral radiculopathy. Am J

Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;79:60-68; quiz 75-66.

)($ Long A, Donelson R, Fung T. Does it matter

which exercise? A randomized control trial of exercise for low back pain. Spine. 2004;29:25932602.

33. Luo X, Pietrobon R, Sun SX, Liu GG, Hey

L. Estimates and patterns of direct health

care expenditures among individuals with

back pain in the United States. Spine.

2004;29:79-86. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.

BRS.0000105527.13866.0F

34. Maitland GD. Vertebral Manipulation. 6th ed.

Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2002.

35. McKenzie R, May S. The Lumbar Spine: Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy. 2nd ed. Waikanae,

New Zealand: Spinal Publication, Ltd; 2003.

36. Moore JH, Goss DL, Baxter RE, et al. Clinical

diagnostic accuracy and magnetic resonance

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

*($

43.

44.

imaging of patients referred by physical therapists, orthopaedic surgeons, and nonorthopaedic providers. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther.

2005;35:67-71. http://dx.doi.org/10.2519/

jospt.2005.1344

Ostelo RW, de Vet HC, Waddell G, Kerckhoffs

MR, Leffers P, van Tulder MW. Rehabilitation

after lumbar disc surgery. Cochrane Database

Syst Rev. 2002;CD003007. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1002/14651858.CD003007

Pendergrass TL, Moore JH. Saphenous neuropathy following medial knee trauma. J Orthop

Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34:328-334. http://

dx.doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2004.1269

Rhee JM, Schaufele M, Abdu WA. Radiculopathy

and the herniated lumbar disc. Controversies

regarding pathophysiology and management. J

Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:2070-2080.

Rubin DI. Epidemiology and risk factors for

spine pain. Neurol Clin. 2007;25:353-371.

Saal J. Post-operative rehabilitation and training. In: Mooney V, Gatchel R, Mayer T, eds. Contemporary Conservative Care for Painful Spinal

Disorders. Philadelphia, PA: Lea & Febiger;

1991:318-327.

Scrimshaw SV, Maher CG. Randomized controlled trial of neural mobilization after spinal

surgery. Spine. 2001;26:2647-2652.

Shapiro S. Cauda equina syndrome secondary to lumbar disc herniation. Neurosurgery.

1993;32:743-746; discussion 746-747.

Shapiro S. Medical realities of cauda equina

syndrome secondary to lumbar disc herniation.

Spine. 2000;25:348-351; discussion 352.

45. Small SA, Perron AD, Brady WJ. Orthopedic pitfalls: cauda equina syndrome. Am J Emerg Med.

2005;23:159-163.

46. Springer BA, Arciero RA, Tenuta JJ, Taylor DC.

A prospective study of modified Ottawa ankle

rules in a military population. Am J Sports Med.

2000;28:864-868.

47. Springer BA, Gill NW, Freedman BA, Ross AE,

Javernick MA, Murphy MP. Acetabular labral

tears: diagnostic accuracy of clinical examination by a physical therapist, orthopaedic surgeon, and orthopaedic resident [abstract]. J

Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36:A82.

48. Tarulli AW, Raynor EM. Lumbosacral radiculopathy. Neurol Clin. 2007;25:387-405. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1016/j.ncl.2007.01.008

49. Vath SA, Owens BD, Stoneman P. Insidious onset

of shoulder girdle weakness. J Orthop Sports

Phys Ther. 2007;37:140-147.

50. Vroomen PC, de Krom MC, Wilmink JT, Kester

AD, Knottnerus JA. Diagnostic value of history

and physical examination in patients suspected

of lumbosacral nerve root compression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72:630-634.

51. Weishaar MD, McMillian DM, Moore JH. Identification and management of 2 femoral shaft

stress injuries. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther.

2005;35:665-673. http://dx.doi.org/10.2519/

jospt.2005.2180t

@

CEH;?D<EHC7J?ED

WWW.JOSPT.ORG

CHECK Your References With the JOSPT Reference Library

JOSPT has created an EndNote reference library for authors to use in

conjunction with PubMed/Medline when assembling their manuscript

references. This addition to “INFORMATION FOR AUTHORS” on the JOSPT

website under “Complete Author Instructions” offers a compliation of all

article reference sections published in the Journal from 2006 to date as

well as complete references for all articles published by JOSPT since

1979—a total of nearly 10,000 unique references. Each reference has been

checked for accuracy.

This resource is updated monthly with each new issue of the Journal. The

JOSPT Reference Library can be found at http://www.jospt.org/aboutus/

for_authors.asp.

journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy | volume 39 | number 7 | july 2009 | 549