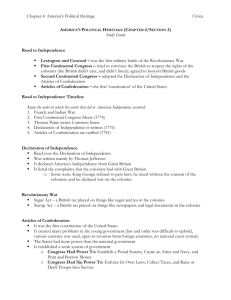

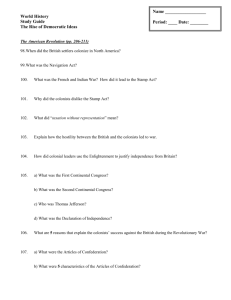

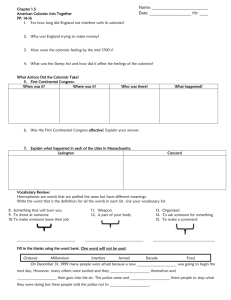

Chapter 3: The American Revolution, 1754-1789

advertisement