The influence of social and physical factors and out-of

The influence of social and physical factors and out-of-home eating on food consumption and nutrient intake in the materially deprived older UK population

Final report to the WRVS

Bridget Holmes and Caireen Roberts

Submitted March 2009

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge WRVS for funding this secondary analysis and the following for their contribution to the report: Ms Sam Clemens and Ms Heather Wardle from the National Centre for Social Research, Dr Lisa Wilson from the Caroline Walker Trust, Mr

Mark Chatfield from the MRC Human Nutrition Research and Professor Judith Buttriss and

Ms Sara Stanner from the British Nutrition Foundation. LIDNS was funded by the Food

Standards Agency and carried out by the National Centre for Social Research, King’s

College London, and the Royal Free and University College London Medical School.

1

Contents

1 BACKGROUND TO THE PROJECT.............................................................................................. 4

1.1

I NTRODUCTION AND AIM ............................................................................................................. 4

1.2

T HE L OW I NCOME D IET AND N UTRITION S URVEY (LIDNS)........................................................... 6

2 BACKGROUND TO THE ANALYSES ........................................................................................... 7

2.1

D IETARY VARIABLES .................................................................................................................. 7

2.2

N ON DIETARY VARIABLES ........................................................................................................... 7

2.3

E ATING AT HOME AND OUT OF HOME .......................................................................................... 7

2.4

D IETARY R EFERENCE V ALUES ................................................................................................... 8

2.5

D ATA ANALYSIS ......................................................................................................................... 9

3 RESULTS...................................................................................................................................... 11

3.1

B ODY M ASS I NDEX .................................................................................................................. 11

3.2

S OCIAL AND PHYSICAL FACTORS AND THEIR INFLUENCE ON FOOD AND NUTRIENT INTAKE ............. 11

3.2.1

Household type and social isolation.................................................................................. 11

3.2.2

Main food shop.................................................................................................................. 12

3.2.3

Cooking skills of the Main Food Provider (MFP)............................................................... 12

3.2.4

Limiting physical factors .................................................................................................... 13

3.2.5

Self-described appetite ..................................................................................................... 13

3.2.6

Self-reported oral health.................................................................................................... 14

3.3

R EGRESSION FOR FOOD AND NUTRIENT INTAKE IN RELATION TO SOCIAL AND PHYSICAL FACTORS . 14

3.4

E ATING AT HOME OR OUT OF HOME .......................................................................................... 16

4 DISCUSSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................................................ 18

REFERENCES...................................................................................................................................... 21

TABLES ................................................................................................................................................ 24

2

Summary

There are many causes of less healthy eating patterns and nutritionally inadequate diets in the older population, particularly among those living in poverty, and this means that preventing, identifying and overcoming risk factors is often a complex issue. The present analysis investigated factors for less healthy eating patterns, sub-optimal nutrient intakes and the influence of the social setting (eating at-home or out-of-home) on diet quality in men and women aged 65 and over from the national survey of low income households in the UK.

The analysis showed substantial evidence of nutritionally inadequate diets in both men and women. Those limited by a long standing illness or disability generally had less healthy eating patterns and lower nutrient intakes and this was most apparent for men aged 75 and over. Men and women reporting a good appetite and no difficulty chewing were more likely to have a healthier diet than those with an average or poor appetite or those who experienced difficulty chewing.

Social isolation proved to be of particular concern with 72% of men and 58% of women reporting that they did not eat out at least once a fortnight. Eating out-of-home appeared to have a positive influence on diet, for men in particular, with higher energy intakes on ‘eating out-of-home’ days compared with ‘eating at home’ days and generally higher nutrient intakes. Men and women who ate alone (as opposed to eating with others) and those who ate on their lap (as opposed to at a table) were more likely to have a nutritionally inadequate diet. Older men living in households where the person responsible for shopping and preparing food had less developed cooking skills, had a less healthy and nutritionally adequate diet. Overall, our results indicated that older men were not only less likely to eat out, but also less likely to cook when at home and would potentially benefit most from support with food and cooking that extends beyond standard meals-on-wheels provision and includes eating out more, ideally with others.

3

1 Background to the project

1.1

Introduction and aim

Recent statistics show that for the first time, a higher proportion of the UK population is aged over 60 than under 16 (ONS 2008). Those of pensionable age constitute nearly 20% of the population, with those aged 80 years and over the fastest growing group. This age group has increased between 1981 and 2007 from 2.8% to 4.5%, mainly as a result of improvements in rates of mortality.

The prevalence of overweight is high in the older UK population, however a major concern is that older people are not eating enough (Caroline Walker Trust 2004). Although as age increases, energy requirements decrease with lessening activity, insufficient food intake invariably results in a low intake of nutrients. It is estimated that 1 in 10 people aged over 65 and living in the community are experiencing some form of malnutrition (European Nutrition for Health Alliance 2006). At its worst, malnutrition results in protein-energy malnutrition which is associated with impaired muscle function, immune dysfunction, and poor wound healing and delayed recovery from surgery (Domini et al 2003). More common in developed countries such as the UK is a sub-optimal micronutrient intake from a nutritionally inadequate diet. The level of risk of nutritional deficiency varies greatly within individuals as the barriers to healthy eating are social, physical and psychological: they include underlying disease, loss of appetite, decreased mobility, limited transport to local shops with healthy affordable food and social isolation. Furthermore, older people are more likely to experience food poverty and suffer the consequences of the widening gap in health inequalities in the

UK.

For many older people the problems of a nutritionally inadequate diet are linked to the ability to shop and cook. The problem is exacerbated by factors which may lead to a lack of interest in food such as bereavement, depression and ill health. Those who have spent their lives cooking for a family or partner may lack the interest in cooking for themselves when alone

(Centre for Policy on Ageing 2002, Age Concern, 2006). Others may not know how to cook: small studies have shown that men often struggle to cook for themselves when widowed

4

(Howarth 1993) and their eating habits are positively influenced by a woman’s presence in the household (Donkin et al . 1998).

Therefore, community meals, including meals delivered to the home and meals served at, for example, day centres, have the potential to contribute greatly to the nutrient intake of individuals who cannot shop, cook or provide a hot main meal for themselves. Home care services including community meals therefore play a vital role in supporting older people to remain in their own home where previously they would have gone into residential care. The

Caroline Walker Trust has issued nutritional guidelines to ensure community meals meet minimum recommendations for older people for energy and other key nutrients (2004).

Additionally, oral heath plays a major part in food choice and diet quality in the older population. Twenty percent of older people reported that poor oral health prevented them from eating foods they would otherwise choose (Locker 1992) and dietary variety (a measure of diet quality), is reportedly lower in subjects with fewer total teeth, fewer functional teeth or ill-fitting dentures (Marshall et al 2002).

A further important factor to consider when looking at barriers to an adequate diet in the older population is the social aspect of eating. A study investigating the nutritional needs of older people living alone identified social and psychological factors that can increase appetite and motivation to eat (Jones et al 2005). These included cooking or eating with others, smelling food as it was being cooked and being involved in conversations around food – activities in which many older people cannot or do not have the chance to participate in. Getting out of the house and being active were also effective in stimulating a poor appetite.

Recently published analysis on men aged 65 and over who participated in a national dietary survey of low income households in the UK (LIDNS) identified those factors with the most striking differences in terms of food consumption and nutrient intake to be level of cooking skills, long standing illness or disability, poor oral health and smoking status (Holmes et al .

2008). The aim of the present analysis was to further investigate risk factors for less healthy eating patterns and sub-optimal nutrient intakes in both men and women aged 65 and over in LIDNS, exploring the influence of the social setting (eating at-home or out-of-home) on diet quality. These results will feed into future primary research needs by identifying where recommendations need to be focused to improve the diet of those at greatest risk.

5

1.2

The Low Income Diet and Nutrition Survey (LIDNS)

The full LIDNS methodology is set out in the Main Report (Nelson et al . 2007). Briefly, an index of material deprivation assessed via a doorstep screening questionnaire was used to establish eligibility of households for inclusion in the survey with the aim of identifying the bottom 15% of the population. In eligible households, up to two respondents were randomly selected to take part; if children were present, one adult and one child were selected; otherwise two adults were selected. The key stages of the survey, administered by trained interviewers and nurses, involved a face-to-face interview and self-completion questionnaire, dietary data collection, anthropometric measurements (which varied by age) and the collection of blood samples (in those 8 years and over) to measure indices of nutritional status.

The LIDNS dataset contained 3728 respondents (unweighted). Of these, 725 were aged 65 or over and living either on their own or with one or more adults, all of retirement age: 119 men and 227 women aged 65-74, and 115 men and 264 women aged 75 and over. This group formed the basis for the analysis presented here. All LIDNS respondents were free living.

6

2 Background to the analyses

Dietary data collection used the 24-hour recall ‘multiple pass’ method repeated on four nonconsecutive days based on the method used in the US (Moshfegh et al. 1999) but modified for use in the Low Income Diet Methods Study (LIDMS) (Nelson et al.

2003) and again for

LIDNS (Nelson et al . 2007). Further details can be found in the Main Report (Nelson et al .

2007). Food consumption and energy and nutrient intakes are reported as measured i.e. no adjustment has been made for physical activity or possible mis-reporting of dietary data.

Results should therefore be considered with this in mind.

2.2

Non-dietary variables

The face-to-face interview was completed with all selected respondents in the household.

Information was obtained on health (including oral health), appetite, smoking and where and with whom respondents usually ate their meals. Additional questions were also asked of the

Main Food Provider (MFP) - the person in the household with the main responsibility for shopping and preparing food if he or she was not one of the selected respondents. These questions covered access to shops and cooking skills. Responses from the MFP interview were applied to all individuals within the household at the analysis stage.

2.3

Eating at-home and out-of-home

For each eating or drinking occasion in the 24-hour recall, the respondent was asked to select the place/source of consumption from a show card. This identified where the item was consumed, for example at home, work or elsewhere and where the food came from, for example home, work, takeaway outlet, or other retail outlet. Table 1 shows the place and source codes used in the 24-hour recall.

At-home eating was defined to include consumption of all foods and drinks consumed at the location coded as A in Table 1. Out-of-home eating was defined to include consumption of all foods and drinks at any of the locations coded as B through to Q (inclusive) in Table 1,

7

irrespective of the place of purchase or preparation. This definition has been used previously

(Orfanos et al.

2007).

Table 1. Place and source codes used in the 24-hour recall

Place

N

O

P

Q

I

J

K

L

M

D

E

F

G

H

A

B

C

Home, own food supply

Home, take-away brought in

Home, other food brought in, paid for

Home, other food brought in, free

Friend's or Relative's house

Restaurant or Cafe

School (bought food or drink)

School (food or drink from home)

School (free/other)

Work (bought food or drink)

Work (food or drink from home)

Work (free/other)

Pub, bar, lounge, hotel, club

Take-away eaten away from home

Other place (bought food or drink)

Other place (food or drink from home)

Other place (free/other)

To identify out-of-home eaters of substantial quantities, any days for which respondents consumed 25% or more of their daily energy intake through eating out were classified as eating out-of-home days (Orfanos et al.

2007). Any days for which respondents consumed

50% or more of their daily energy intake through missing place codes were removed from the subsequent analyses. All remaining days were classified as eating-at-home days.

Mean food and nutrient values were calculated for each respondent according to whether the days were ‘at-home’ or ‘out-of-home’. Only those respondents with days classified as ‘athome’ and ‘out-of-home’ were included in the analysis.

2.4

Dietary Reference Values

Mean nutrient intakes are expressed as a percentage of the relevant Dietary Reference

Value (DRV). DRVs comprise a series of estimates of the amount of energy and nutrients needed by different groups of healthy people in the UK population.

Energy intake is expressed as a percentage of the Estimated Average Requirement (EAR).

For a given population group, it is expected that approximately 50% of each sex and age group will have energy requirements above the EAR and 50% will have requirements below

8

the EAR. The mean energy intake for a given group in which all members were meeting their individual requirements would, therefore, be expected to be equal to the EAR.

Nutrient intakes for protein, total fat, saturated fat, total carbohydrate, non-milk extrinsic sugars and alcohol were expressed as a percentage of energy. Non-milk extrinsic sugars

(NMES) include table sugars and added sugars (e.g. in soft drinks, cakes and confectionery) as well as sugars in fruit juice.

Intakes of all other nutrients are expressed as a percentage of the Reference Nutrient Intake

(RNI). The RNI is the amount of that nutrient that is sufficient, or more than sufficient, for about 97% of the people in the group for whom the RNI is defined. They are not minimum targets. For further information see Department of Health (1991).

Energy intake as a percentage of the EAR and protein, vitamin and mineral intakes as a percentage of the RNI were calculated for each respondent individually, using the EAR or

RNI appropriate for their sex and age.

2.5

Data analysis

Comparisons of food consumption and nutrient intake between subgroups were carried out using the statistical package SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS Inc 2006). Food group analysis is based on all respondents i.e. both consumers and non-consumers of a food. Data presented in the report are based on food only data i.e. not including supplements. All results are based on weighted data so that the reported findings reflect the demographic characteristics of the UK low income population as a whole. Comparisons between groups were made using complex models unpaired t-tests or general linear models (ANOVA) unless otherwise stated.

Multi-variable logistic regression was carried out using STATA/SE9.1 (StataCorp 2007) to examine the non-dietary social and physical factors associated with foods and nutrients of particular interest or policy relevance. The dependent variables investigated were consumption of wholemeal bread, fruit and vegetables and intakes of vitamin C, iron, nonstarch polysaccharide (NSP) (often referred to as dietary fibre) and NMES. Binary variables for wholemeal bread, fruit and vegetables were created according to sex specific weighted median values for those aged 65 and over living alone or with one other retired adult from

LIDNS. The median is the middle of a distribution: half the values are above the median and half are below. For example the median intake for portions of vegetables for men was 1.34.

9

Binary variables for vitamin C and iron were created based on those who met or exceeded the RNI and those who did not. Intakes of NSP were grouped according to whether or not intakes had met the minimum recommended level of 12 grams per day, while intakes of

NMES were grouped according to whether or not more than 11% of food energy had been derived from NMES.

The independent variables included in the models were the social and physical factors: household type, who meals were eaten with at home on a weekday, main food shop, cooking skills of the MFP, limited shopping and/or food preparation, self-described appetite and chewing ability (see Table 3). In addition, age, current smoking status, main type of food shop used, where meals were eaten at home on a weekday and if meals were eaten out at least fortnightly were included. The variables were chosen specifically as they were identified as factors likely to be associated with food consumption and nutrient intakes in people aged

65 and over.

Independent variables were entered into the model based on those most strongly associated with each dependent variable according to Pearson correlation coefficients. Although the models were run separately for men and women, factors of significance in the model for one sex were included in both models.

10

3 Results

3.1 Body Mass Index

Table 2 shows the distribution of the sample by Body Mass Index (BMI) (weight in kilograms divided by height in metres squared). The categorization of BMI for adults used for this report is based on that used in other surveys, such as the National Diet and Nutrition

Surveys (NDNS). Of the 662 respondents where BMI data was available, 71% of men and

74% of women were overweight or obese (BMI >25) and 2% of men and 1% of women were classified as underweight (BMI ≤ 18).

3.2

Social and physical factors and their influence on food and nutrient intake

Table 3 shows the proportion of men and women who lived alone compared with those living with other adults of retirement age. Men and women aged 75 and over were more likely to be living on their own. Living alone was strongly associated with eating alone during the week (chi squared p<0.001). Ninety-four percent of all respondents who lived alone usually ate on their own on weekdays.

Overall those eating alone consumed significantly more fat spreads and less chips, fried and roast potatoes than those who ate with others. Men eating alone consumed more white bread and non diet soft drinks. For both men and women aged 75 and over, eating alone meant a higher consumption of wholemeal bread compared with those eating with others.

There were very few consistent differences in terms of nutrient intakes.

Table 3 shows that 69% of men and 57% of women ate their meals at the table (as opposed to on their lap or on the go) on weekdays. The main differences in food consumption between the two groups indicated that women eating at the table had higher intakes of fruit and vegetables though lower intakes of baked beans. These differences in food consumption may account for the higher intakes of vitamin A, C and potassium. Lower

11

intakes of sugar, preserves and confectionery were also seen in the women who ate their meals at the table. Overall men and women who ate at the table consumed more meat and meat dishes and had higher intakes of protein and iron than those who ate on their lap or on the go.

Respondents were more likely to eat at the table regardless of whether they ate their meals alone or with others: 57% of those who ate alone and 70% of those who ate with others ate at the table (Fisher’s exact test p<0.05).

Respondents were also asked if they ate a meal out at least once a fortnight. Of the 516 who responded, significantly more did not eat out at least once a fortnight (63%). Women were more likely to eat out at least once a fortnight than men (42% compared with 28%). Eating out was associated with a higher proportion of energy from total fat for men and a higher intake of vitamin C for women.

Six percent of respondents consumed food at home that was classed as ‘other food brought in, paid for’ on one or more of the days for which dietary data was collected (see Table 1).

This is likely to compose mainly of food supplied by meals on wheels. Small numbers meant that analysis could not be undertaken separately on this group.

3.2.2 Main food shop

Respondents who lived in households in which the main shop used for purchasing food was a large supermarket were compared with those that relied primarily on small supermarkets, local/corner shops, garage forecourts or street markets. Few differences were seen in food consumption patterns for men or women according to shopping practices. While men who lived in households in which the main shop used for purchasing food was a large supermarket consumed more dairy produce e.g. milk and cream and yoghurt, this pattern was not generally observed in women.

3.2.3 Cooking skills of the Main Food Provider (MFP)

Table 3 shows that 25% of men lived in households where the MFP had ‘less developed’ cooking skills (better developed skills were defined as those able to prepare a main dish from basic ingredients unaided; those unable to do this were defined as having less developed skills) compared with 7% of women. The majority (93%) of men with less developed cooking skills lived on their own.

12

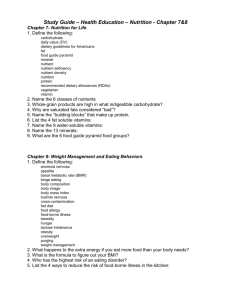

Men aged 75 and over living in households where the MFP had less developed cooking skills consumed significantly lower amounts of vegetables, wholemeal bread, white fish and fish dishes, chips, fried and roast potatoes, and other potatoes, and diet soft drinks than men in households where the MFP had better developed cooking skills. This group of men were particularly at risk of low intakes of energy and other nutrients (Figure 1).

3.2.4 Limiting physical factors

Twenty-seven percent of men and 36% of women reported that their food shopping and /or food preparation was limited by a long standing illness or disability (Table 3). While few significant differences were observed in the food consumption data for women, men aged 65 and over whose food shopping and/or preparation were not limited, consumed significantly greater amounts of wholemeal bread, milk and cream and fruit. More differences and differences of a greater magnitude were generally observed in men aged 75 and over.

While mean nutrient intakes were generally higher in men and women whose food shopping and/or food preparation was not limited, very few of the differences were significant for women. Table 4 presents the mean daily intake of nutrients as a percentage of the DRV and as a percentage of energy from macronutrients for men aged 65-74 and 75 and over, by whether or not their food shopping and/or preparation were limited. While differences for men aged 65 and over were apparent (see Holmes et al, 2008), when this analysis was split by age, it was the men aged 75 and over for whom the differences were significant. Men aged 75 and over whose food shopping and/or food preparation was not limited had significantly higher intakes for the majority of nutrients, and a lower percentage of their food energy from NMES compared with those whose food shopping and/or food preparation was limited. Very few differences in nutrient intake remained significant for men aged 65-74.

3.2.5 Self-described appetite

Respondents were asked to rate their appetite as good, average or poor for someone of their age (see Table 3). Men and women with a good appetite (57% and 50% respectively) were compared with those who reported having an average or poor appetite (42% and 50% respectively). Men aged 65 and over with an average or poor appetite consumed more alcoholic drinks compared with those with a good appetite. While men aged 65-74 with a good appetite consumed significantly more vegetables than other men, men aged 75 and over with a good appetite consumed significantly more fruit juice. A higher mean intake of

13

vitamin C as a percentage of the RNI was observed in men aged 75 and over with a good appetite.

Women aged 65 and over with a good appetite consumed significantly more meat and meat dishes, vegetables and other potatoes (not chips, fried or roast) compared with those with an average or poor appetite. These differences were observed in younger and older women but differences were more apparent in the older group. Figure 2 presents intakes of selected nutrients as a percentage of the DRV for women aged 65 and over, by appetite level.

Women with a good appetite had higher intakes for all nutrients compared with those with an average or poor appetite. Additionally, women with an average or poor appetite derived a higher percentage of their food energy from NMES and saturated fat and a lower percentage from protein compared with those with a good appetite.

3.2.6 Self-reported oral health

Respondents were categorised into two groups – those who experienced no difficulty chewing (70%) and those who experienced difficulty, either a little, some or a great amount

(30%) (Table 3). Chewing ability had an effect on consumption of vegetables for men and women in both age groups, with those who had difficulty chewing consuming significantly lower amounts. They also consumed less meat and meat dishes. Those aged 75 and over with difficulty chewing consumed less wholemeal bread. The differences observed in food consumption were reflected in generally lower nutrient intakes for those who experienced difficulty chewing including protein, folate and potassium. This group also obtained higher percent food energy from NMES and saturated fat.

3.3

Regression for food and nutrient intake in relation to social and physical factors

Six separate logistic regression models are presented. For all models, the independent variable is significantly associated with the outcome variable if p<0.05. Only variables that were significant in the final model are presented in the table (although in some instances results are presented for men or women where one or the other was significant). The odds associated with the outcome variable are presented for each category of the independent variable. Odds are expressed relative to a reference category, which is given the value of 1.

References groups were determined based on those most likely to have a positive outcome in relation to food or nutrient intake. An odds ratio greater than 1 indicates higher odds, while

14

an odds ratio lower than 1 indicates lower odds. 95% confidence intervals are also shown for each odds ratio. In some of the models, the number of available cases to analyse was small and as a result the confidence intervals surrounding the odds ratios presented for some subgroups and categories are large.

Table 5 presents a model of the non-dietary factors associated with consuming the median or above in number of portions of fruit for women. Women who did not eat out at least once a fortnight were less likely to consume the median number of portions of fruit or above compared with women who did eat out (odds ratio 0.4). Women who were current smokers were less likely to consume the median number of portions of fruit or above compared to those who did not smoke (odds ratio 0.5). No significant differences were observed for men.

Table 6 presents a model of the non-dietary factors associated with consuming the median or above the median number of portions of vegetables. Women aged 75 and over, women who had an average or poor appetite and women who experienced difficulty chewing were less likely to consume the median number of portions of vegetables or above. For men, ability to chew was the only significant predictor of a higher vegetable consumption. Men who experienced difficulty chewing were more likely to consume above the median number of portions of vegetables compared with men who had no difficulty but this result is most likely due to very small numbers in one or more of the sub-groups.

Table 7 presents a model of the non-dietary factors associated with consuming the median or above the median intake of wholemeal bread. For both men and women, those who reported that their food shopping and /or preparation was limited by a long standing illness or disability were less likely to be consuming the median intake or over for wholemeal bread compared with those that reported no limitations (odds ratios 0.4 for men and 0.6 for women). Also, men who experienced difficulty chewing were less likely to be consuming the median intake or over the median intake of wholemeal bread compared with those who had no difficulty (odds ratio 0.4).

Table 8 presents a model of the non-dietary factors associated with a vitamin C intake that met or exceeded the RNI. Men living in households where the MFP had less developed cooking skills were less likely to have a vitamin C intake that met the RNI compared to men living in households where the MFP had better developed cooking skills. Women who were current smokers were less likely to meet the RNI for vitamin C, a reflection of their consumption of fewer portions of fruit, than women who were not current smokers. For both

15

men and women, those who reported having an average or poor appetite were less likely to be meeting the RNI for vitamin C compared with those who reported having a good appetite.

Table 9 presents the only significantly associated non-dietary factor for deriving no more than 11% of food energy from non-milk extrinsic sugars (NMES), by sex. Men and women aged 75 years and over were more likely than those aged 65-74 years to derive more than

11% of food energy from NMES (odds ratios 0.5 for both men and women).

Table 10 presents a model of the non-dietary factors associated with consuming 12g or more per day of NSP for women. Women aged 75 years and over, those who were current smokers and those who ate their meals on their lap or on the go were less likely to consume

12g or more of NSP (age odds ratios 0.6, current smoker odds ratio 0.2, where eats odds ratio 0.5). None of the non-dietary factors were significantly associated with NSP intake in men.

3.4

Eating at-home or out-of-home

As described in the methods section, days of data were classified as either ‘eating at-home’ or ‘eating out-of-home’. Results presented within this section are separate to those describing whether or not respondents ate out at least fortnightly. Table 11 shows the mean daily consumption of foods by eating at-home or out-of-home. Consumption of biscuits, fruit pies, buns, cakes and pastries, white fish and fish dishes, chips, fried and roast potatoes and fried potato products was higher on days when men and women ate out-of-home (not always significant). This was also the case for fruit juice (significant for women only, 42g vs 27g), and alcoholic drinks, for which intake on out-of-home days was over double that on eating at-home days (men 512g vs 216g, women 54g vs 17g).

Consumption of fat spreads and other potatoes (not chips, fried or roast) was lower on eating out-of-home days in men and women. A lower consumption of fruit was also observed on these days in both men (61g vs 77g) and women (74g vs 115g). Consumption of yoghurt, fromage frais and dairy desserts was lower on eating out-of-home days but only for women.

Table 12 shows the mean nutrient intake as a percentage of the DRV by eating at-home or out-of home. Generally higher nutrient intakes were seen on eating out-of-home days for men, while the reverse was seen for women.

16

Higher energy intakes as a percentage of the EAR were observed in men and women on eating out-of-home days (significant for men only). On eating out-of-home days, intakes of vitamin B6, folate, magnesium and iodine were significantly higher in men and the percentage of food energy from saturated fat was lower.

For women, significantly lower intakes of protein, riboflavin and vitamin B6 were seen on eating out-of-home days. They also had a lower percentage of food energy from protein and a higher percentage from NMES and total fat on eating out-of-home days.

For both men and women, alcohol contributed twice as much to their energy intake on eating out-of-home days.

Days for which respondents consumed 25% or more of their daily energy intake through eating out were classified as eating out-of-home days, in line with the literature (Orfanos et al

2007). This classification system is arbitrary to some extent and it is assumed that eating out-of-home days are correlated with eating out-of-home in general. Additionally, out-ofhome eating was defined according to the place of consumption, irrespective of the place of purchase or preparation, and therefore some misclassification may have resulted.

Our analysis included only those respondents who had days classified as ‘at-home’ and ‘outof-home’ so therefore in some cases data may be based on only one day for any one individual. Mean values are not likely to be affected although corresponding standard deviations will tend to increase (Willet, 1998).

17

4 Discussion and Recommendations

In the older population there are many causes of less healthy eating patterns and nutritionally inadequate diets, particularly among those living in poverty, and this means that preventing, identifying and overcoming risk factors is often complex.

Results from this analysis show that levels of underweight in the low income older population who live at home are low, with 2% of men and 1% of women classified as underweight.

Equivalent figures reported in the National Diet and Nutrition Survey of people aged 65 years and over were 3% for men and 6% for women, while figures for those in residential care were higher, 16% and 15% respectively (Finch et al 1998). Our results showed large proportions of the group were classified as overweight or obese (71% of men and 74% of women) and there was substantial evidence of nutritionally inadequate diets.

Social isolation proved to be of particular concern in our sample, with low levels of eating out recorded, particularly for men: 72% of men and 58% of women reported that they did not eat out at least once a fortnight. The positive contribution eating out makes to overall diet is shown by the higher energy intakes on ‘eating out-of-home’ days compared with ‘eating at home’ days for men and women, and generally higher nutrient intakes as a percentage of the DRV for men. Eating out of home has previously been linked to a sedentary lifestyle and higher energy intakes in adults aged 35 – 74 years (Orfanos et al 2007). Our results suggest that eating out generally had a positive influence on nutritional intake in older people, especially in men who are less likely to cook meals at home, but that healthy food choices and advice on healthy eating should be made available to consumers.

In terms of the eating environment at home, the food consumption data suggested that those who ate alone may be substituting a cooked meal or hot meal for food that can be easily prepared such as sandwiches. Those who ate alone and those who ate on their lap (as opposed to at a table) appeared to be most likely to have a nutritionally inadequate diet.

Older people living in households where the MFP had less developed cooking skills generally had a less healthy and nutritionally adequate diet and this was particularly noticeable in the older men. Overall, our results indicated that older men were not only less likely to eat out, but also less likely to cook when at home.

18

While the type of shop that men and women used to purchase their food didn’t seem to influence food and nutrient intake, how easy it was for a person to get to the shop to purchase food did. Older people who were limited by a long standing illness or disability generally had less healthy eating patterns and lower nutrient intakes. Again this result was most apparent for men, but particularly so for men aged 75 and over. These results are in line with those reported elsewhere which suggest that older people who experience the greatest difficulties in food shopping are considered to be at the greatest nutritional risk

(Herne 1995; McKie 1999).

Nutritional adequacy of older people’s diet according to level of appetite indicated that men and women reporting a good appetite were more likely to have a healthier diet than those with an average or poor appetite. Interpretation of appetite as an influencing factor on dietary intake is problematic since it is linked to other factors such as long standing illness or disability limiting food preparation, poor oral heath and ability to chew, social isolation and current smoking status. Additionally appetite is difficult to measure and self-reporting may introduce bias into the results. Oral health played an important role in food consumption and nutrient intake with those older people who had poor chewing ability generally consuming lower amounts of vegetables and having lower nutrient intakes, with higher intakes of NMES.

The Caroline Walker Trust (2004) stresses that it is not just a case of improving what older people eat but also how much they eat. It suggests the importance of stimulating appetite in older people and suggests that snacks should be provided in between more formal mealtimes or, in the case of community meals, be delivered with the main meal, thereby ensuring that, if they wish, older people can eat a little at a time, but more frequently.

Relationships between intakes in terms of our cut-offs i.e. intakes at or above the median

(for foods) or DRVs (for nutrients) and our social and physical factors varied for men and women. Associations were generally in the direction that would be expected, for example, those with average or poor chewing ability were less likely to consume the median intake of vegetables. It should be noted that often median intakes were still very low, for example median intakes of fruit and vegetables were still well below the Department of Health’s recommendation of at least five portions per day. Social and physical factors that appeared to be consistently linked to less healthy food consumption patterns and lower nutrient intakes were having an average or poor appetite, poor chewing ability, shopping and/or food preparation being limited by long standing illness or disability, and factors relating to social isolation including eating out at least once a fortnight, eating alone and eating on one’s lap.

19

These results reinforce the importance of the social aspects of eating for older people. Men seem to be at particular risk and would benefit from learning how to eat better at home but also to eat more meals with others outside the home. Projects such as ‘Recipe for Life’ aim to help older people who live alone to eat well by developing innovative ways of providing support with food and eating that maintain the positive social and psychological benefits associated with food that may be lost with conventional community meals (Jones et al 2005).

Eating with familiar others has been shown to increase food intake by 60% in healthy older adults (McAlpine et al 2003) so advantage should be taken of any opportunities for social eating. The Caroline Walker Trust Expert Working Group has recommended that lunch clubs should be developed for older people in any setting where it is already the custom for older people to gather (Caroline Walker Trust, 2004). In addition, research in the US has shown that by expanding community meals-on-wheels to include breakfast, energy and nutrient intakes could be improved and depressive symptoms reduced. The researchers recommended that the addition of a breakfast service to traditional home delivered meals services could be of great benefit to the older population living at home (Gollub et al 2004).

We suggest that this should be done in conjunction with other measures that support social eating.

20

References

Age Concern England & National Consumer Council (2006) ‘Fit as Butcher’s Dogs? A report on healthy lifestyle choice and older people’, Age Concern Reports.

Caroline Walker Trust (2004). Eating well for older people. Practical and nutritional guidelines for food in residential and nursing homes and for community meals. 2 nd ed. CWT:

Herts.

Centre for Policy on Ageing (2002) ‘Hard Times – A Study of Pensioner Poverty, CPA &

Nestle Family Monitor.

Department of Health (1991) Report on Health and Social Subjects, No 41. Dietary

Reference Values for Food Energy and Nutrients for the United Kingdom. Report of the

Committee on Medical Aspects of Food Policy

. HMSO: London.

Domini LM, Savina C, Cannella C. (2003) Eating habits and appetite control in the elderly: the anorexia of ageing. International Psychogeriatrics, 15: 73-87.

Donkin AJW, Johnson AE, Lilley JM et al . (1998) Gender and living alone as determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption among elderly living at home in Nottingham. Appetite , 30 :

39-51.

European Nutrition for Health Alliance (2006) Malnutrition among Older People in the

Community: Policy Recommendations for Change . European Nutrition for Health Alliance:

London

Finch S, Doyle W, Lowe C et al

. (1998)

National Diet and Nutrition Survey: people aged 65 years and over. Volume 1: Report of the diet and nutrition survey . TSO: London.

Gollub EA, Weddle DO (2004) Improvements in nutritional intake and quality of life among frail homebound older adults receiving home delivered breakfast and lunch . J Am Diet

Assoc, 104 : 1227-1235.

Herne S. (1995) Research on food choice and nutritional status in elderly people: a review.

British Food Journal , 97 (9): 12-29.

21

Holmes B, Roberts C, Nelson M. (2008) How access, isolation and other factors may influence food consumption and nutrient intake in materially deprived older men in the UK.

Nutrition Bulletin, 33 : 212–220.

Howarth G (1993) Food consumption, social roles and personal identity. In : Ageing, independence and life (eds S Arber & M Evandrou). Jessica Kingsley: London

Jones C, Dewar B, Donaldson C. (2005) Recipe for life: helping older people eat well . Queen

Margaret University College: Edinburgh.

Locker D. (1992) The burden of oral disorder in a population of older adults. Community

Dent Health; 9 (2): 109-24

Marshall TA, Warren JJ, Hand JS et al. (2002) Oral health, nutrient intake and dietary quality in the very old. J Am Dent Assoc , 133 : 1369–79

McAlpine S J, Harper J, McMurdo M E et al.

(2003) Nutritional supplementation in older adults: pleasantness, preference and selection of sipfeeds. British Journal of Health

Psychology, 8 : 57–66.

McKee L. (1999) Older people and food: Independence, locality and diet. British Food

Journal , 101 (7): 528-537.

Moshfegh AJ, Borrud LG, Perloff BP et al

. (1999) Improved method for the 24-hour dietary recall for use in national surveys [abstract]. Journal of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology,

13(4): A603. http://www.statistics.gov.uk/cci/nugget.asp?ID=949 Internet source produced by National

Statistics Online, UK. [Electronically accessed 12 th Dec 2008]

Nelson M, Dick K, Holmes B et al. (2003) Low Income Diet Methods Study. Food Standards

Agency: London.

Nelson M, Erens B, Bates B et al . (2007) Low Income Diet and Nutrition Survey. TSO:

London. Available from: http://www.food.gov.uk

22

Orfanos P, Naska A, Trichopoulos D et al.

(2007) Eating out of home and its correlates in 10

European countries. The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition

(EPIC) study. Public Health Nutrition, 10(12): 1515-1525.

SPSS Inc. SPSS for Windows: Release 15.0, Chicago, Illinois: SPSS Inc. 2006.

StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 9. College Station, Texas: Stata Corporation.

2007.

Willet WC (1998) Nutritional epidemiology, 2 nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

23

Table 2. Distribution of sample, by sex, age and body mass index (BMI (kg/m 2 ))

BMI

65-74 years 75+ years 65+ years 65-74 years 75+ years 65+ years 65+ years

% % % % % % %

Underweight ( ≤ 18.5) - 3 2 1 2 1 1

Normal weight (>18.5, ≤ 25) 27 29 28 20 28 24 26

Overweight (>25, ≤ 30)

Obese (>30, ≤ 40)

43 41 42 32 41 37 39

27 26 27 41 29 34 32

2 1 2 6 0 3 2

114 108 222 212 228 440 662

- No observations

24

Table 3. Distribution of sample, by sex, age and social and physical factors

Social and physical factor Men Women Total

Household

65-74 years 75+ years 65+ years 65-74 years 75+ years 65+ years 65+ years

% % % % % % %

Who meals are eaten with at home on a weekday

Living with other(s) 54 30 41 25 16 20 26

Alone 51 62 58 72 82 78 71

49 38 42 28 18 22 29

Where meals are eaten at home on a weekday

On lap or on the go 42 23 31 43 42 43 39 food

Small developed 84 68 75 96 92 93 87

16 32 25 4 8 7 13

No 74 72 73 66 63 64 67 Long standing illness or disability limiting shopping and/or food preparation

26 28 27 34 37 36 33

Good 54 60 57 55 46 50 52

Average or poor 46 40 42 45 54 50 48 ability

Difficulty

119 115 234 227 264 491 725

MFP, Main Food Provider - the person in the household with the main responsibility for shopping and preparing food.

* Bases apply to household type, main food shopping, limited shopping and/or food preparation and chewing ability and vary slightly for all other characteristics.

25

Figure 1. Mean daily intake of nutrients as a percentage of the Dietary Reference Value (DRV)

(Estimated Average Requirement or Reference Nutrient Intake) for men aged 75 and over, by cooking skills of main food provider (selected significant differences) (n=115)

160

140

Better cooking skills

Less cooking skills

120

100

80

60

40

20

0

En erg y

Pr ote in

Fo lat e

Po tassi um

Ma gn es ium

Co pp er

Zin c

Iro n

Io din e

26

Table 4. Mean daily intake of nutrients as a percentage of the Dietary Reference Value (DRV) and as a percentage of energy from macronutrients, by sex and whether or not shopping, food preparation or both are limited by a long standing illness or disability

Nutrient Men 65-74 years Men 75 years and over

Not limited Limited

P

Not limited Limited

P Mean

Percentage of DRV

Energy (% EAR)

Protein (% RNI)

81

139

74

128

88

134

79 *

114 **

Vitamin A (% RNI)

Vitamin D (% RNI)

Thiamin (% RNI)

Riboflavin (% RNI)

Niacin equivalent (% RNI)

Vitamin C (% RNI)

Vitamin B6 (% RNI)

Vitamin B12 (% RNI)

Folate (% RNI)

Potassium (% RNI)

Calcium (% RNI)

Magnesium (% RNI)

(%

Iron (% RNI)

152

34

171

137

215

166

157

404

135

79

126

31

160

118

196

143

137

378

117

72

*

129

81

113

72

226 202

119 115

Copper (% RNI)

Zinc (% RNI)

Iodine (% RNI)

% food energy from non-milk extrinsic sugars

% food energy from protein fat fat

94

92

140

Percentage of energy

47.5

11.5

75 **

85

130

13.2

17.0 16.7

36.5 35.7

14.3 14.5

% energy from alcohol 4.4 3.3

157

455

137

78

126

80

191

36

185

146

216

165

150

38

141 **

111 **

179 **

134

122 **

337

102 **

62 **

98 **

64 **

127

100

91

140

101

82

**

70 **

47.3

106 **

48.8

13.2 16.1 *

16.5 15.8

36.2 35.4

14.7 14.2

4.0 5.4

* P <0.05, ** P <0.01

EAR Estimated Average Requirement

RNI Reference Nutrient Intake

27

Figure 2. Mean daily intake of nutrients as a percentage of the Dietary Reference Value (DRV) for women aged 65 and over, by appetite level (selected significant differences) (n=491)

250

Good appetite

Average or poor appetite

200

150

100

50

0

Pro te in

Vi ta mi n

C

Vi ta mi n

D

Fo lat e

Po ta ss ium

Ma gn esi um

Pho sph or us

Iro n

Zinc

28

Table 5. Estimated odds ratios for consuming above the median daily intake for fruit (portions) a women, by associated non-dietary factors

for

P

Eats out fortnightly

Eats out at least fortnightly

(unweighted)

Odds ratio 95% CI

130 1

Does not eat out at least fortnightly

Question not answered

Yes

Question not answered/never smoked

208

153

0.4

0.9

0.26 - 0.74

0.49 - 1.67

0.002

Current smoker

No 188 1

87

216

0.5

0.9

0.25 - 0.93

0.56 - 1.60

0.029

491 a Median portions of fruit (this includes a maximum of one portion fruit juice) per day was 1.1 for women.

29

Table 6. Estimated odds ratios for consuming above the median daily intake for vegetables (portions) a , by associated non-dietary factors and sex

Men

Age

65 - 74 years

(unweighted)

Odds ratio 95% CI

119 1

P

Women

Age

65 - 74 years

(unweighted)

227 1

95% CI P

75 years and over

Appetite

A good appetite

An average or poor appetite for someone their age

Question not answered

Ability to chew

No difficulty

Difficulty experienced (little, fair or great)

115

128

105

1

168

66

1.2

1

0.6

-

1

0.3

0.65 - 2.38 0.515

Appetite

A good appetite

0.28 - 1.18 0.131

75 years and over

-

0.14 - 0.77 0.011

An average or poor appetite for someone their age

Ability to chew

No difficulty

Difficulty experienced (little, fair or great)

Question not answered

234 a Median portions of vegetables (this includes a maximum of one portion of beans and pulses) per day was 1.3 for men and 1.4 for women

264

243

248

334

156

1

0.5

0.5

1

0.3

0.33 - 0.87 0.011

0.19 - 0.50 0.000

0.33 - 0.79 0.003

1 - -

491

30

Table 7. Estimated odds ratios for consuming above the median daily intake for wholemeal bread (grams) a , by associated non-dietary factors and sex

Men

Limited shopping and/or food preparation limited

(unweighted)

Odds ratio 95% CI P

Women

1 preparation limited

(unweighted)

P

317

Limited

Ability to chew difficulty

Difficulty experienced (little, fair or great)

63

168 1

66

0.4

0.4 a Median daily intake of wholemeal bread was 0.0g for men and women

234

0.14 - 0.91 0.030

0.17 - 0.95 0.037

Limited

Ability to chew difficulty

Difficulty experienced (little, fair or great)

174 0.6 0.37 - 0.95 0.030

334 1

156 1.03 0.67 - 1.59 0.879

491

31

Table 8. Estimated odds ratios for meeting or exceeding the Dietary Reference Value (DRV) for vitamin C intake, by associated non-dietary factors and sex

Men

Cooking skills

Better developed

(unweighted)

Odds ratio 95% CI

183 1

P

Women

Cooking skills

Better

(unweighted)

454 1

P

Less developed 51 0.4 0.18 - 0.91 0.029 Less developed

Question

35

2

0.4

0.3

0.14 - 1.27 0.129

0.01 - 8.72

Appetite

A good appetite

An average or poor appetite for someone their age

Question

Eats out fortnightly

Eats out at least fortnightly

Does not eat out at least fortnightly

Question not answered

Current smoker

No

Yes

Question not answered/never smoked

128

105

50

128

56

1

0.3

5.3

Appetite

0.17 - 0.64 0.001

A good appetite

An average or poor appetite for

1 someone their age

- -

Eats out fortnightly

1

1.8 0.74 - 4.33 0.193

1.85 - 15.15

Eats out at least fortnightly

Does not eat out at least fortnightly

Question not answered

Current

54

52

0.4

0.9

234

0.18 - 1.10 0.079

0.41 - 2.16

Yes

Question not answered/never smoked

243

248

130

208

153

87

216

1

0.6

1

0.6

1.3

0.4

1.0

491

0.34 - 0.92 0.022

0.35 - 1.07 0.082

0.65 - 2.47

0.22 - 0.84 0.014

0.59 - 1.78

32

Table 9. Estimated odds ratios for deriving no more than 11% of food energy from Non-milk extrinsic sugars (NMES), by associated non-dietary factors and sex

Men

Age

65 - 74 years

(unweighted)

Odds ratio 95% CI

119 1

P

Women

Age

65 - 74 years

(unweighted)

227

P

1

75 years and over 115 0.5

234

0.26 - 0.91 0.024 75 years and over 264 0.5

491

0.34 - 0.84 0.007

33

Table 10. Estimated odds ratios for consuming 12g or more per day a of non-starch polysaccharides (NSPs) for women, by associated non-dietary factors

P

Age

65 - 74 years

(unweighted)

227 1

75 years and over 264 0.6 0.37 - 0.96 0.035

Current smoker

No

Yes

Question not answered/never smoked

0.9

0.11 - 0.53

0.53 - 1.46

0.000

188 1

87

216

0.2

Where eats on a weekday the

On lap or on the go

279 1

209 0.5 0.28 - 0.73 0.001

Question not answered 3 -159.89

491 a 12grams is the minimum recommended daily intake of NSP.

34

Table 11. Mean daily consumption of food (grams) (including non-consumers), by sex and eating at-home or out-of-home

Food group

Pasta, rice, pizza and other cereals

White and other bread bread

Men

Athome

Outof-

Women All

P Athome

Outof-

P Athome

Mean (g)

Mean (g)

Wholegrain and high fibre cereals

Other breakfast cereals

Mean (g)

Mean (g) consumer

Biscuits, fruit pies, buns, cakes and pastries Mean (g)

Puddings including ice cream

Milk and cream

Cheese

Yoghurt, fromage frais and dairy desserts

Mean (g) consumer

Mean (g) consumer

Mean (g) consumer

Mean (g) consumer

Eggs and egg dishes

Fat

Meats and meat dishes, excluding processed meat

Processed meat including sausages,

8

17

90 home

19

20

85

88

19

23

44

44

6

23

36

70

44

39

203

93

10

31

10

13

29

48

82

18

21

34

40

8

24

45

68

*

37

32

200

94

7

22

11

8

19

35

94 91

140 120

88

34

86

37

19

28

52 home

19

25

50

87

16

29

27

49

6

26

38

83

75

14

24

29

43

6

21

45

75

31

39

42

43

225 213

100 100

*

9

41

27

28

14

37

9

29

13 **

14

13

27

94

111

89

23

84

92

78

21

16

25

63

Outofhome

19

P

24

60

88

17

28

32

47

6

25

38

80

35

39

219

98

9

38

23

24

18

40

94 86

119 100 *

89

27

81

26

77

15

23

30

42

6

22

45

73

*

41

39

209

98

9

27

12 **

12

15

29 burgers, coated chicken

White fish and fish dishes Mean (g) consumer

Oily fish and dishes Mean (g) consumer

Vegetables exc potatoes and baked beans Mean

Baked

Chips, fried and roast potatoes and fried potato products

Other potatoes, potato salads and dishes, potato products cooked without fat

Crisps and savoury snacks

Fruit, excluding fruit juice

Sugar, preserves and confectionery juice

Soft drinks, not diet

Soft drinks, diet

Mean (g)

Mean (g)

Mean (g)

Mean (g)

Alcoholic drinks, including low alcohol

Tea, coffee and water

Mean (g)

Mean (g) consumer

(g)

53

17

20

35

42

36

*

10

22

4

8

118 110

84 76

17

15

6

6

40

17

30

28

36 **

31

8

19

3

6

*

114 106

87 80

6

10

6

5

29 53

92 55

31 51

* 78 55

66

6

22

77

38

3

14

61

68

2

12

115

49

2

10

74 **

56

30

45

33

72

22

57

23

83 83

13 18

70 67

27 42

13

53

26

22

10

216

38

1068

12

83

27

14

8

512

50

1120

**

21

49

29

37

15

17

18

1162

22

56

25

37

14

54 **

25

1154

100 100

58 54

100 100

72 45

64 70 79 68

44

17

27

30

38 **

32

8

20

3 **

6

115 108

86 79

9

11

6

6

31 52

**

68

3

15

104

46

2

11

70 **

67

24

54

26

74 72

*

19

50

29

33

13

74

23

1135

19

64

26

30

13

186 **

32

1144

100 100

*

75 69

Base (unweighted) † 100 100 248 248 348 348

*

†

P <0.05, ** P <0.01

Only those respondents with days classified as ‘at-home’ and ‘out-of-home’ were included in the analysis.

35

Table 12. Mean daily intake of nutrients as a percentage of the Dietary Reference Value (DRV) and as a percentage of energy from macronutrients, by sex and eating at-home or out-of-home

Nutrient

Percentage of DRV

Vitamin A (% RNI)

Vitamin

Niacin equivalent (% RNI)

Vitamin C (% RNI)

Men Women

Athome

Outofhome

P Athome

Outofhome

P Athome

Outofhome

P

Mean Mean Mean Mean Mean Mean

** 79 82 81 84

133 135 131 125 * 132 128

*

128 135

39 35

201 188

28 24

180 173

**

177 171

129 136

180 166

148 138 * 143 138

205

153

221

150

241

181

227

163

231

173

225

159

387 374 341 319

126 143 * 116 115

354 335

119 123

74 78 68 67

107 106

70 70

109 109

* 72 71

211 223 185 182

73 75

121 117 107 104

82 91 ** 73 74

111 108

75 79

(%

Iodine

Percentage of energy

% food energy from total carbohydrate

% food energy from non-milk extrinsic sugars

132 154 * 116 116

47.2 47.4

12.8 13.6

47.6 47.2

121 127

47.5 47.2

11.6 12.6 * 12.0 12.9 *

% food energy from protein

% food energy from total fat

16.5 16.7

36.4 35.8

17.2 16.1

35.2 36.7 * 35.5 36.5

% food energy from saturated fat

% energy from alcohol

14.4 13.3

3.6 ** 0.9 2.0

14.4 14.3

**

Base (unweighted) †

*

†

P <0.05, ** P <0.01

Only those respondents with days classified as ‘at-home’ and ‘out-of-home’ were included in the analysis.

EAR Estimated Average Requirement

RNI Reference Nutrient Intake

100 100 248 248 348 348

36

Contacts

Dr Bridget Holmes

Nutritional Sciences Division

King’s College London

150 Stamford Street

London

SE1 9NH

United Kingdom

Tel: + 44 (0)20 7848 3360

Email: bridget.holmes@kcl.ac.uk

Ms Caireen Roberts

National Centre for Social Research

35 Northampton Square

London

EC1V 0AX

United Kingdom

Tel: + 44 (0)20 7549 7063

Email: caireen.roberts@natcen.ac.uk

WRVS

Garden House

Milton Hill

Steventon

Abingdon

OX13 6AD

United Kingdom

Email: enquiries@wrvs.org.uk

37

38