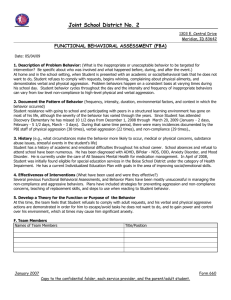

Introduction to Biopsychosocial Approaches to Studying the

advertisement