Austen on the Screen

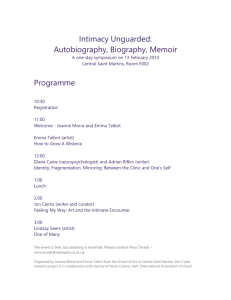

advertisement