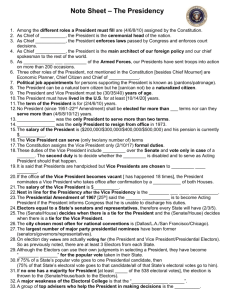

a constitutional chameleon: the vice president's place within the

advertisement