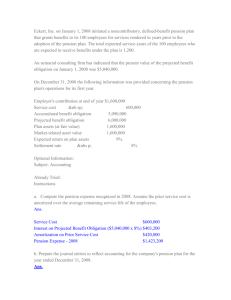

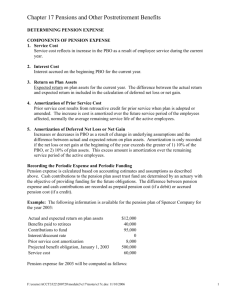

Accounting for Pensions and Postretirement Benefits 20

advertisement