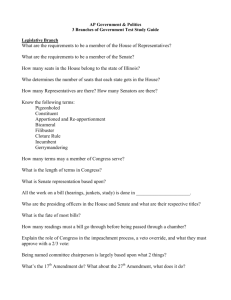

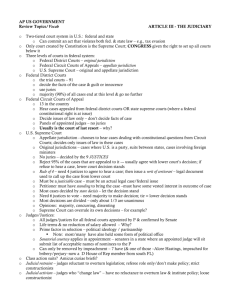

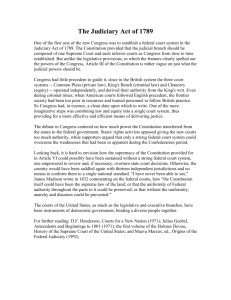

The Federal Courts - Jb-hdnp

advertisement