"Good to Great" Policing: Application of Business Management

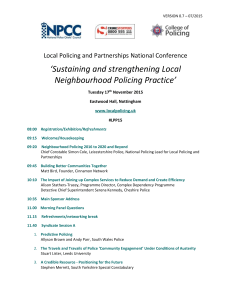

advertisement