The Evolution of the Joint Stock Company to 1800

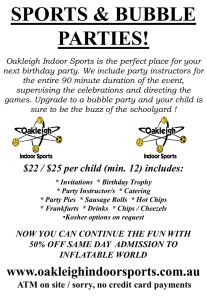

advertisement