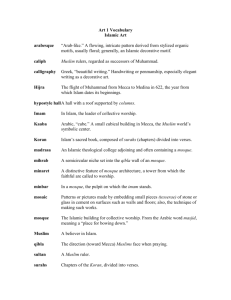

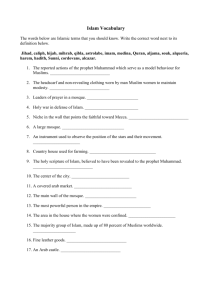

Leading the Community of the Middle Way: A Study of the Muslim

advertisement