Adam Smith's Invisible Hands

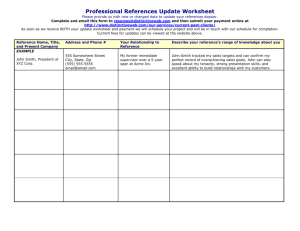

advertisement