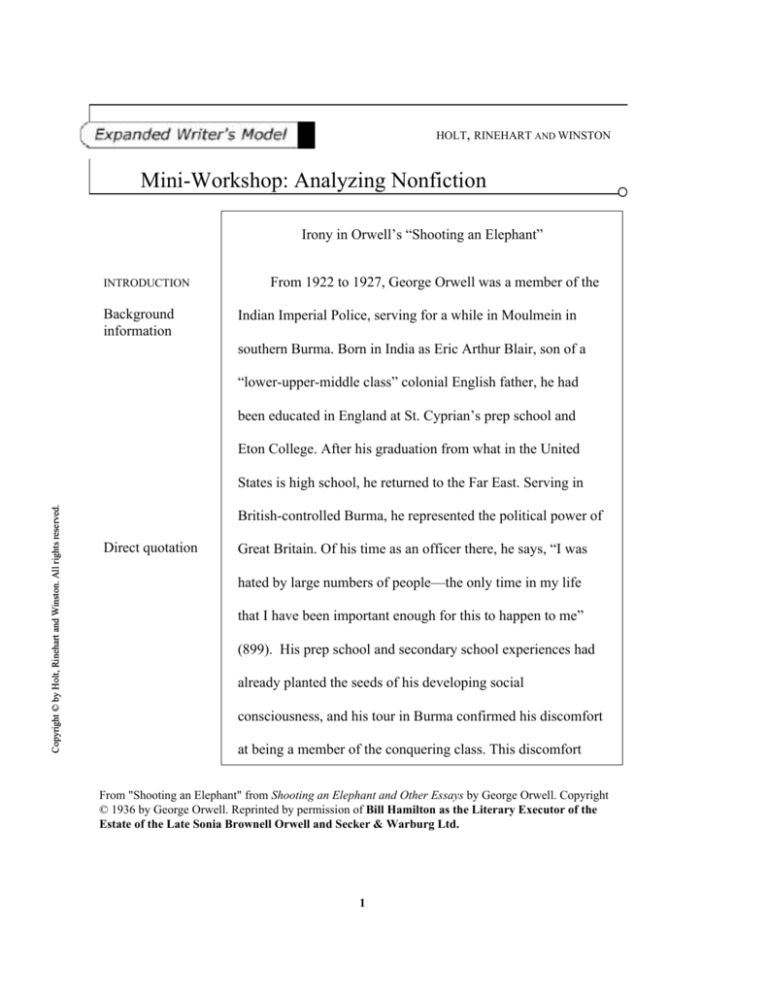

HOLT, RINEHART AND WINSTON

Mini-Workshop: Analyzing Nonfiction

Irony in Orwell’s “Shooting an Elephant”

INTRODUCTION

Background

information

From 1922 to 1927, George Orwell was a member of the

Indian Imperial Police, serving for a while in Moulmein in

southern Burma. Born in India as Eric Arthur Blair, son of a

“lower-upper-middle class” colonial English father, he had

been educated in England at St. Cyprian’s prep school and

Eton College. After his graduation from what in the United

Copyright © by Holt, Rinehart and Winston. All rights reserved.

States is high school, he returned to the Far East. Serving in

British-controlled Burma, he represented the political power of

Direct quotation

Great Britain. Of his time as an officer there, he says, “I was

hated by large numbers of people—the only time in my life

that I have been important enough for this to happen to me”

(899). His prep school and secondary school experiences had

already planted the seeds of his developing social

consciousness, and his tour in Burma confirmed his discomfort

at being a member of the conquering class. This discomfort

From "Shooting an Elephant" from Shooting an Elephant and Other Essays by George Orwell. Copyright

© 1936 by George Orwell. Reprinted by permission of Bill Hamilton as the Literary Executor of the

Estate of the Late Sonia Brownell Orwell and Secker & Warburg Ltd.

1

HOLT, RINEHART AND WINSTON

Mini-Workshop: Analyzing Nonfiction

provides the backdrop for his first published essay, “A

Hanging” (1931), and for his first novel Burmese Days, (1934).

Title of essay

Author

In his much-anthologized essay “Shooting an Elephant,”

George Orwell graphically describes an incident that he

experienced as a young police officer in colonial Burma.

Called to handle an elephant in “must” that is on the rampage

and has killed a native, Orwell realizes too late that he will

Copyright © by Holt, Rinehart and Winston. All rights reserved.

have to shoot the elephant, a valuable piece of property

belonging to its absent Burmese mahout (elephant keeper), not

because of the danger that the elephant poses to the natives, but

to save face, especially because he represents British colonial

power. Orwell’s description of the unfortunate incident reveals

his attitudes toward both himself as a colonial officer and the

Thesis statement

natives he policed. To communicate his theme that tyranny

debases the oppressors as much as the oppressed, Orwell

ironically describes this incident he experienced as a young

police officer in colonial Burma.

Key point 1:

Situational irony

As a subdivisional police officer in Moulmein, Orwell

2

HOLT, RINEHART AND WINSTON

Mini-Workshop: Analyzing Nonfiction

finds himself in several ironic situations. First, he is required to

carry out publicly policy he does not believe in privately. As

Evidence: direct

quotations

representative of the imperialist government, his job allows

him to see “the dirty work of Empire at close quarters” (899).

Much of the work he does fills him with guilt because of the

conditions he must enforce. He finds the scenes of “the

wretched prisoners huddling in the stinking cages of the

lockups, the gray, cowed faces of the long-term convicts” (899)

Copyright © by Holt, Rinehart and Winston. All rights reserved.

to be oppressive. However, privately, he despises the people

who taunt him in public; the natives infuriate him with their

insults and jeers. He is the object of ridicule in public, and he

confesses that he would like nothing better than to “drive a

bayonet” into his taunters (900). He finds himself “stuck

between [his] hatred of the empire [he] serve[s] and [his] rage

against the evil-spirited little beasts who tried to make [his] job

Elaboration

impossible” (900). Orwell finds his situation intolerable but

impossible to escape. He also finds it impossible to escape the

consequences of such a situation.

Key point 2:

Situational irony

His account of his killing an elephant dramatizes one of

3

HOLT, RINEHART AND WINSTON

Mini-Workshop: Analyzing Nonfiction

those consequences of his ironic situation—a second example

Evidence:

Summary

of situational irony. Alerted to the dangers of the elephant,

which has killed a coolie (unskilled worker) in its rampage,

Orwell borrows an elephant gun. Only when the natives think

that he is going to shoot an elephant do they become interested

Elaboration

enough to follow him. Ironically, the natives are not interested

in the elephant as long as it is raging. They become interested

only when they see Orwell’s gun and realize they might

Copyright © by Holt, Rinehart and Winston. All rights reserved.

capitalize on a source of free meat.

Evidence:

Summary

When Orwell sees the elephant, now standing passively

and eating, he realizes that the elephant’s “must” has passed.

Yet because the crowd, swelling to some two thousand people

behind him, expect him to kill the elephant, Orwell feels he

must bend to their will. Because he fears the crowd’s laughter

at his failure to act more than he fears the elephant owner’s

Evidence: Direct

quotation

anger, he proceeds with his task. This situation of doing

something because the crowd of natives wants him to and

expects him to dramatizes “the real nature of imperialism—the

Elaboration

real motives for which despotic governments act” (900). He

4

HOLT, RINEHART AND WINSTON

Mini-Workshop: Analyzing Nonfiction

has acted not out of necessity, not even for a moral reason, but

because his failure to act might make him look foolish in the

Evidence: Direct

quotation

eyes of the natives. After all, “a sahib has got to act like a

sahib; he has got to appear resolute, to know his own mind and

Elaboration

do definite things” (902). The irony is that Orwell is not sure of

his own mind and he does a “definite thing” (killing an

elephant) so poorly that its value was debated afterward.

Key point 3:

Situational irony

A third example of situational irony is the actual

Copyright © by Holt, Rinehart and Winston. All rights reserved.

elephant kill. Orwell finds himself in the ironic position of

being called on to perform a task for which he is ill-suited.

Evidence:

Paraphrase

Orwell admits to the reader that he was not an experienced

marksman, nor did he know then exactly where he should aim

to make the most efficient rifle shot. Moreover, the ground is

soft mud, and he must lie down “on the road to get a better

Elaboration

aim” (903). His lack of preparation for the task he is called on

to perform is thematic in his essay. At that point in its history,

the British Empire, Orwell indicates, was ill-prepared to rule

from halfway around the world a people so different and

resentful of its presence.

5

HOLT, RINEHART AND WINSTON

Mini-Workshop: Analyzing Nonfiction

Key point 4:

Verbal irony

Throughout his essay, Orwell’s tone is straightforward

and unemotional as he reports the details of the incident. The

objectivity of his reporting style sets up his use of verbal irony.

Sometimes the result of his irony is humorous. For example,

when he describes the natives’ glee at seeing him march toward

the paddy fields a few hundred yards away, he comments,

Evidence: Direct

quotation

“They had not shown much interest in the elephant when he

was merely ravaging their homes, but it was different now that

Copyright © by Holt, Rinehart and Winston. All rights reserved.

Elaboration

he was going to be shot” (901). The impact of the sentence’s

verbal irony turns on the word merely. Orwell indicates the

natives are thrill seekers, not caring as much for their own

welfare when it is threatened by the elephant as they do for the

excitement and entertainment of watching a dangerous

confrontation between man and elephant. His use of verbal

irony indicates his contempt for the foolishness of the natives

that value sport over their own safety.

Key point 5:

Verbal irony

Orwell uses verbal irony for serious purposes also. For

example, another effect of his unemotional tone is that it

conveys and intensifies the horror of the elephant-killing

6

HOLT, RINEHART AND WINSTON

Mini-Workshop: Analyzing Nonfiction

Evidence:

Summary

incident. He cites in great detail the various steps he took to

accomplish his task. Misaligning his first rifle shot, he shoots

again and again. When the elephant still continues to breathe,

Orwell fires his final two rifle shots into the animal’s heart.

The elephant continues its tortured breathing, “powerless to

move and yet powerless to die” (904). Retrieving a smaller

rifle, Orwell empties it into the beast’s heart and throat, trying

to stop the unnerving sound of the animal’s dying breaths, but

Copyright © by Holt, Rinehart and Winston. All rights reserved.

to no avail. Walking away in disgust at his own inefficiency,

Orwell learns later that the animal took at least thirty more

minutes to die before its flesh was stripped to the bones by the

Elaboration

knife-wielding crowd of natives. By describing his role in the

death of the elephant in such detail and with such an

unemotional tone, Orwell underscores his use of verbal irony,

since the number of explicit details obviously plays upon the

readers’ feelings.

Key point 6: Final

irony

A final dimension of Orwell’s irony is related to his use

of the details as symbols. Orwell’s perspective—an older man

narrating events of his young adulthood—invites the reader to

7

HOLT, RINEHART AND WINSTON

Mini-Workshop: Analyzing Nonfiction

consider his expanded description of the death of the elephant

as symbolic, especially because of historical changes and

events between the time that Orwell was a youth and an adult.

As Orwell documents the changes in the elephant from living

animal to carcass, he describes the scene so that it almost

seems to happen in slow motion. The animal is stunned, then

Evidence: Direct

quotation

slowly falls to its knees, rises, then falls again after Orwell

shoots for the third time. “But in falling he seemed for a

Copyright © by Holt, Rinehart and Winston. All rights reserved.

moment to rise, for as his hind legs collapsed beneath him he

seemed to tower upward like a huge rock toppling, his trunk

reaching skyward like a tree. He trumpeted, for the first and

only time. And then down he came . . . with a crash that

seemed to shake the ground. . . .” (904). The overall image is of

a huge animal struggling mightily with what has happened to it.

In addition to the slow motion of the description, Orwell

also emphasizes the elephant’s apparent age. In the aftermath

Evidence: Direct

quotation

of his first shot, “a mysterious, terrible change had come over

the elephant. . . . He looked suddenly stricken, shrunken,

immensely old. . . . An enormous senility seemed to have

8

HOLT, RINEHART AND WINSTON

Mini-Workshop: Analyzing Nonfiction

settled upon him. One could have imagined him thousands of

Elaboration

years old” (903–904). Both the slow death and the age of the

elephant suggest a parallel to the slow decline of the British

Empire. Orwell suggests that, like the elephant, the British

Empire was dying a long, slow, messy death. Orwell invites

Evidence: Direct

quotation

that comparison when earlier in his essay he observes, “I did

not even know that the British Empire [was] dying, still less

did I know that it [was] a great deal better than the younger

Copyright © by Holt, Rinehart and Winston. All rights reserved.

Elaboration

empires that [were] going to supplant it” (900). Of course, the

irony underlying his comment is that Orwell uses himself to

represent the agent of death to the British Raj—a young,

inexperienced officer, swayed by the unarmed will of a people,

who abandons the results of his efforts to the natives and their

dahs (sharp, heavy knives).

CONCLUSION

In “Shooting an Elephant,” Orwell crystallizes his

ambivalent feelings about being an officer in Burma. As an

agent of the empire, he was required to enforce a system whose

aims and methods he rejected. He understood and sympathized

with the Burmese people’s anti-European attitude, yet their

9

HOLT, RINEHART AND WINSTON

Mini-Workshop: Analyzing Nonfiction

behavior infuriated him. He reveals himself to the reader as

foolish and inept—characteristics he could not admit to the

thousands of natives who watched him shoot an elephant.

Restatement of

thesis

Orwell’s use of irony in describing the natives’ behavior before

and after the incident, as well as his own, establishes the

Final thought

incident as symbolic. Orwell’s essay indicates that the British

Copyright © by Holt, Rinehart and Winston. All rights reserved

Raj was doomed, but that the countries it left behind perhaps

would fall victim to the practices of scavengers.

10