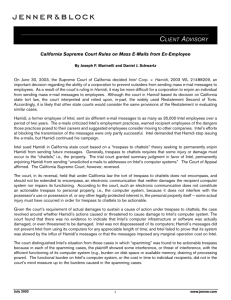

The Trouble With Trespass - Arizona State University

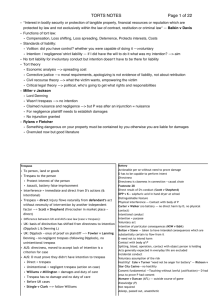

advertisement