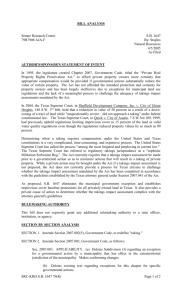

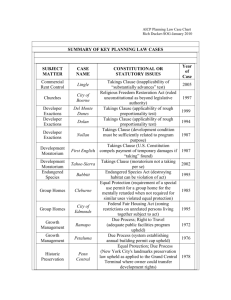

Full Text - Stanford Law School Student Journals

advertisement