Distribution versus Delegation: Federal Grants-in

advertisement

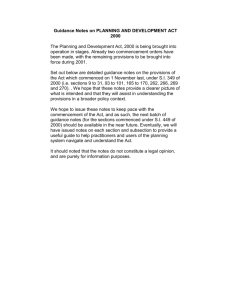

Distribution versus Delegation: Federal Grants-in-Aid, Intergovernmental Policymaking Authority and Congressional Representation Pamela Clouser McCann University of Southern California Anthony M. Bertelli New York University March 22, 2015 DRAFT: PLEASE DO NOT CITE OR QUOTE WITHOUT PERMISSION Abstract: Congress commonly uses grants-in-aid (GIA) to target funds to states for the implementation of significant domestic policies. We argue that individual MCs care about both ex ante and ex post oversight over the spending programs on which they vote, and recognize that agency costs remain insuring that their constituents maintain their distribution of funds. MCs prefer to minimize the time and effort needed to reduce such agency loss ex post, and the decentralization of implementation through GIA has an impact on the costliness of such effort. We employ a unique dataset that captures all grants-in-aid provisions included in all House and Senate bills and public laws during the 93rd-111th congresses and find evidence that: MCs are less likely to support bills as implementation becomes more decentralized when they share partisanship with the president or both political executives; and when members either share party affiliation with only their governors or with neither of these political executives, the likelihood of support rises with decentralization. Paper prepared for the 3rd Annual Southern California Law & Social Science Forum. We thank Nathaniel Beck and George Krause for helpful suggestions. Mistakes remain our own. Congress cannot force the states to implement national policy, but it can provide encouragement. The majority of significant legislation passed by Congress relies on state implementation of national policies (McCann 2015). Whether based on language of federal assistance, relief, or stimulus, money is generally considered an inducement rather than a form of coercion, since participation in grant programs is typically voluntary. Eligibility for these grants often has a statutory basis through formulas based on population or need; explicit rules, such as maintenance of effort requirements, cross-over sanctions, matching funds requirements and other conditions can impact the distribution of grant dollars actually committed to grantees in the individual states. As a result, the design of national-to-state grant programs is manipulable by re-election seeking legislators who calculate the impact of these programs on their electoral constituency (Nathan 1987). This claim is rooted in the logic that legislators’ re-election incentive induces them to prefer to concentrate benefits within their electoral constituencies while spreading costs across the entire nation (Arnold 1990). Distributions of benefits are thus a means of representation (Grose 2011). Grants-in-aid (GIA) provide just such a vehicle of benefits as well as the potential opportunity to stretch federal dollars with matching requirements. Yet, they represent a decentralized mechanism of policy implementation, leaving policy implementation in the hands of state rather than federal administrators. Our focus is on the roll-call voting decision of a member of Congress (MC) and we take a transaction cost politics approach in theorizing about this decision (e.g., Epstein and O’Halloran 1999; Dixit 1996). We claim that the MC wants to minimize the costs of ex post influence and monitoring to maintain the share of federal funds to which she feels her constituents are entitled. The congressional dominance literature asserts that enacting coalitions consider ex ante means 1 for reducing the costs of ex post oversight of the laws they create (e.g., McCubbins and Schwartz 1984; McCubbins, Noll, and Weingast 1989; Macey 1992). Scholars have considered this problem in a variety of ways, for instance, that Congress is an organization with limited resources to allocate to different items on its agenda (cf. Baumgartner and Jones 1993; 2015) and that individual MCs care not only about position taking on proposed legislation, but also about the extent to which they participate in the legislative process on that proposal (Hall 1996). Consistent with these literatures, we argue that individual MCs care about both ex ante and ex post oversight over the spending programs on which they vote. Their ex ante concern surrounds the formula by which funds are allocated, while they recognize that agency costs remain and consider the cost of engaging in ex post oversight mechanisms—the means of monitoring and influence over the distribution of funds—available to them. The crux of our argument is that MCs prefer to minimize the time and effort needed to reduce agency loss ex post. Ex post oversight over funds allocation can be done through both formal and informal mechanisms, and the mechanisms in each category are costly for MC’s to employ. Formal mechanisms available to MCs include committee hearings involving testimony by administrators and congressional appropriations to agencies. Informal mechanisms involve contacts and consultations between congressional and agency staffers and sharing information about agency choices with the media and relevant organized interests. The core of our theory lies in two claims. First, an important element of implementation—whether the funds are distributed by federal administrative agencies or are left to state implementation via GIA—shapes ex post oversight costs in a meaningful way that influences MCs roll-call voting decisions. Second, 2 party ties between the MC and the political executives at each level, namely, the president and his state’s governor, also influence the costs of ex post action regarding funds distribution. Previous studies of GIAs typically utilize annual federal outlays to the states and localities or compilations of appropriations demarcated as earmarks (e.g., Knight 2008; Larcinese, Snyder and Testa 2010). Because we are interested in their impact on roll-call voting, our focus comes earlier in the legislative process. To capture the degree of decentralization in grant administration, we develop a measure of whether provisions in a given bill are delegated via GIAs to the states, to federal agencies, or through other means. Using a dataset of 70,827 coded provisions and associated roll-call votes in the House and Senate from 199 major laws enacted during the 93rd to 111th Congresses, we find that MCs are less likely to support bills as implementation becomes more decentralized when they share partisanship with the president or their governor, but not both political executives. However, when members either share party affiliation with both or neither of these political executives, the likelihood of support rises with decentralization. We begin with our theoretical argument that MCs consider the costs of oversight in their roll-call voting decisions in regard to spending programs. Our discussion then turns to the data, with particular emphasis on the measurement of decentralization in the implementation. We then describe our statistical modeling technique and present our results before concluding with some brief remarks. A Transaction Cost Politics Theory of Roll-Call Voting on Intergovernmental Grants We argue the costs MCs face for exercising formal ex post oversight are reduced when administrators at the federal level allocate funds. Intergovernmental delegations of such 3 authority to state officials resulting from the use of GIA provisions lead to the involvement of constitutionally separated actors in the administrative process. For instance, it is more difficult for an MC to successfully obtain national hearing testimony from the relevant agency in her state; and a request for GAO review of funds administration for a particular program will broadly examine implementation rather than target only the agency in her state. Informal mechanisms are also more challenging to employ when administration is devolved to the states. At the federal level, administrators are more identifiable and MCs have more centrality in relevant policy networks. Each state’s administrators function within issue networks of political institutions, organized interests and media actors, with individual MCs competing with state politicians and colleagues in the House and Senate from their own states for influence in those networks. Overall, implementation via GIA increases ex post oversight costs for MCs. While decentralization is expected to increase ex post oversight costs for individual MCs, we argue that party ties with political executives further shape these costs. First, co-partisanship with the president reduces the costs of employing formal mechanisms when implementation is centralized. The president can also influence the flow of federal funds—through initial budgetary requests and agency review—to particular states; partisan differences between the president and an MC could decrease the flow of national dollars to her electoral constituency. In American politics, partisanship relates to a politician’s preferences for a variety of spending priorities from social welfare programs to tax expenditures benefiting corporations, which makes party a particularly important proxy for policy conflict in regard to federal expenditures. Moreover, the management of such expenditures can impact the re-election chances of MCs, and presidential co-partisans would be expected to benefit from this fact in the form of less costly formal influence over funds administration. The absence of presidential co- 4 partisanship may also make informal influence more costly. Access to staff in federal agencies and their amenability to the MC’s views and concerns about funds administration is less likely if the MC is from the opposite party from the president. Second, we expect that co-partisanship with the governor of the MC’s home state reduces her costs of engaging formal mechanisms of ex post oversight when administration is decentralized. Formal mechanisms are more costly across federal governing levels for the reasons given above, but when the MC and governor share party affiliation, policy conflict is reduced and spending priorities are more similar. Also, federal funds administered in the MC’s home state as a result of GIA provisions are more likely to benefit her constituents to maintain an electoral advantage over the opposing party. Having a co-partisan governor can also reduce the costs of informal mechanisms of ex post enforcement. Although top state agency staff may be outside of the network of the MC and be more difficult to contact, administrative acceptance of and availability to a co-partisan MC is likely once the correct administrators are reached. We test the following hypotheses arising from these claims. Hypothesis 1 (Presidential Co-Partisanship): An MC who shares the president’s party affiliation, but not that of his state’s governor, is less likely to vote in favor of a proposed bill as its implementation becomes more decentralized. Hypothesis 2 (Gubernatorial Co-Partisanship): An MC who shares the party affiliation of his state’s governor, but not that of the president, is more likely to vote in favor of a proposed bill as its implementation becomes more decentralized. Given the lower cost of engaging formal and informal ex post oversight of federally administered grant programs, MCs sharing party affiliation with both the president and the governor of their home states should find centralization to have lower ex post costs than decentralization. 5 Hypothesis 3 (Full Co-Partisanship): An MC who shares the president’s party affiliation as well as that of his state’s governor is less likely to vote in favor of a proposed bill as its implementation becomes more decentralized. When co-partisanship with either executive cannot mitigate ex post oversight costs, ex post oversight technologies are costlier than in any of the foregoing scenarios. Because of the high cost of informal federal mechanisms in this scenario, the MC may prefer simply to give the state more autonomy. Students of pork-barrel politics literature suggests that MCs can still claim credit for a GIA as a federal benefit to constituents even though we argue here that ex post oversight is more difficult (Bickers and Stein 1995). With high cost ex post oversight at either level, an MC will prefer greater decentralization as it provides, at a minimum, a credit claiming opportunity. Hypothesis 4 (No Co-Partisanship): An MC who shares neither the president’s party affiliation nor that of his state’s governor is more likely to vote in favor of a proposed bill as its implementation becomes more decentralized. Data and Methods To evaluate our claims about the influence of decentralization on MCs’ voting decisions, this study uses the bill, or legislative package, as the unit of analysis with the provision as the unit coded for congressional choice. As more provisions in a given bill include grants to the states, more control over the distribution of resources to constituents shifts to state executives, or, put differently, is decentralized. Alternatively, provisions that delegate such authority to federal administrators without including specific state GIAs shift the locus of control to the national level and thus centralize the distribution of funds. Our dataset includes 70,827 coded provisions from 199 enacted laws from Mayhew’s list of major laws from the 93rd to 111th Congresses (Mayhew 2005, with web updates). We focus on significant, enacted legislation since these are 6 the legislative packages MCs are most likely to have scrutinized and collect text from the final law, the House floor-passed bill, and the Senate floor passed bill. Our binary dependent variable captures the vote choice of each legislator—either a “yea” (coded one) or a “nay” (coded zero) as the MCs final floor vote. Using THOMAS, we identified all major actions for the laws in our dataset and extracted specific measures and associated dates for votes on final passage in both the House and Senate. These votes on final passage were then matched to the appropriate roll-call results from Voteview.com, yielding a collection of legislator’s votes on final passage for each law in the dataset. Dependent Variable Given our argument that the decentralization of a legislative package is crucial to vote choice, we measure decentralization through a delegation ratio, namely, the proportion of a bill or law’s provisions that delegate to the states via GIA. Theoretically, this proportion can vary along the unit interval from zero to one, where zero represents complete centralization to a federal agency with no GIA and one for laws that rely on a GIA to implement every provision. To operationalize intergovernmental delegation via GIA, we begin with a dataset of policy authority delegation across federal actors (McCann 2015), which codes the delegation structure for each law’s major provisions as summarized by the Congressional Research Service (CRS). Specifically, McCann (2015) identifies the entity that received responsibility for implementing a provision, including no delegation, delegation to national-level actors (such as federal agencies), state-level actors, jointly to both national and state actors, as well as delegation to other entities such as the judiciary. Delegation to national-level actors includes establishing new federal agencies, directing new agencies, and specific delegations to the president. Direct 7 delegation to the states is rare and typically focuses on two policy areas: elections and abortion (McCann 2015). Joint delegations of authority to both national and state actors are done either by using GIAs or by simply directing the states and national actors to collaborate on implementation without providing monetary encouragement. Given our theoretical focus on GIA, we separate the two types of joint delegations in our coding process. After carefully reviewing each law’s legislative history, including any and all initial bills for the House and Senate and which bills received action on the floor, we collected CRS summaries of all bills that received a floor vote in the House and likewise for the Senate. If no CRS summary could be located for a Senate or House bill, that bill was coded as missing, which was the case for 30 House bills and 50 Senate bills in the dataset. Overall, the 513 measures (199 final laws, 167 House bills, and 147 Senate bills) resulted in a dataset of 43,396 provisions within congressional bills and 27,432 previously coded provisions from enacted national laws. Because the hand-coding process for over 40,000 provisions is extremely laborious, we relied on automated textual classification using multiple supervised learning algorithms (Collingwood and Wilkerson 2012). A selection of 7,400 previously hand-coded provisions provided a training device for our system of classifying the extent of decentralization in delegations. We used the Rtextools package, which relies on nine machine learning algorithms (see Jurka et al., 2013 and Collingwood and Wilkerson 2012 for an overview). These algorithms approached the uncoded set of provisions within these House and Senate bills after being “taught” the textual patterns within the already handed coded set of provisions. FIGURE 1 ABOUT HERE 8 Figure 1 provides a summary of decentralization within provisions in final laws averaged across congresses. As we expect, Congress delegates the implementation of national laws mainly to national-level actors across time. The second-most common delegation strategy of Congress is to implement national laws via GIA. Two examples of these patterns of delegation are the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB, PL 107-110) and the Affordable Care Act (ACA, PL 111-148), where many provisions decentralize implementation to the states. In the NCLB, 132 provisions were summarized as substantively significant by CRS and included national and state delegations. Of these provisions, 14 delegated authority to national agencies such as the Department of Education with no state involvement, 3 delegated directly to the states with no national involvement, 27 provisions relied on both national and state action for implementation (joint delegations) without using the GIA mechanism, and 88 provisions relied exclusively on GIA. The delegation ratio is 0.667 for NCLB (or 88 grant provisions/132 delegating provisions). In comparison, the delegation ratio for the ACA is 0.256, based on 640 CRS provisions of which 438 delegated to national actors such as the Department of Health and Human Services or the Internal Revenue Service, 38 were joint delegations with no GIAs, and 164 provisions included GIAs (or 164/640, given exclusions). Thus, the NCLB is more decentralized than the ACA. The degree to which Congress employs GIA varies considerably over time. The 100th Congress choose to rely on GIA in about 30% of final enactments, while the 96th Congress used GIA less than 7% of the time. Our delegation ratio includes both broad grants provided to all states as well as narrowly targeted grants. An example of a GIA can be found in P.L. 109-059 (SAFETEA-LU, the Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act) where the Secretary of Transportation is directed to “carry out a grant program to provide financial 9 assistance to states for the cost of local rail line relocation and improvement projects” or in the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1981 (P.L. 97-035) which authorized appropriations to “provide grants to States to assist eligible household to meet the costs of home energy.” It is fruitful to consider differences in the average delegation ratio between Senate bills, House bills, and final enactments as shown in Figure 2. House and Senate bills differ in the proportion of provisions that are delegated to the states via GIA in every Congress. The most similar delegation via GIA occurs in the 97th Congress where the Senate chose to delegate 23.5% of all provisions via grants to the states, the House 23.8% of all provisions, and the final laws delegated 22.9% of provisions to the states via grants-in-aid. More striking differences in delegation ratios within House versus Senate bill choices are found in the 99th or 109th Congresses. In the 99th Congress the Senate included GIA in 14.5% of provisions, the House just over 8% of provisions and the final enactment included GIA in 9.6% of provisions. The 109th House, alternatively, included GIA in 21.7% of provisions versus the Senate’s 17.8% reliance on grants. These two chambers resolved their differences in final enactments that included GIA in only 9% of their provisions. Over time, the Senate relied more heavily on GIA than did the House in 10 of 19 Congresses. Across congresses, the final enactment may include more GIA than either chamber’s bill (100th & 105th Congresses), fewer than either bill (102nd, 104th, 107th, 109-111th Congresses), or an average between the two bills (11 remaining congresses). The highest delegation ratio in enacted laws is 0.786 in P.L. 93-503, the 1974 Amendments to the 1964 Urban Mass Transportation Act. FIGURE 2 ABOUT HERE 10 Partisanship Regimes To capture the political party comparisons required to test our hypotheses, we create a variable partisan regime that takes a value of zero when MCs share party label only with their governors, a one when members share a party label only with the president, two when an MC matches the part of both the president and the home state governor, and a three when an MC is of a different party than both the president and governor. We interact our delegation ratio with this categorical variable. We expect that as decentralization increases, the probability of voting in favor of a measure increases for two types of MCs (gubernatorial co-partisans and members without co-partisan executives) and decreases for the remaining types (presidential co-partisans and members sharing party with both executives). Control Variables We also include a number of control variables expected to influence voting choices: gubernatorial spending power, state fiscal health, divided legislature, federal deficit, and whether it is an election year or not. Spending power was coded as a one for those governors who did have the power to spend unanticipated federal funds without legislative approval and zero otherwise (Krupnikov and Shipan 2011). State fiscal health is the proportion of growth in state own-source revenue from one year to the next, lagged by one year. We expect MCs from states with improving fiscal conditions may not need to provide assistance to their states, yielding a negative coefficient. Alternatively, MCs from states with improving fiscal health may be more likely to use GIA in order to claim credit for successful states (Volden 2005), thus a positive coefficient. We include this term and rely on the empirical analyses to provide support for which mechanism is more common on average. Divided legislature is a 11 dummy variable coded as a one for the years in which the House and Senate are controlled by different majority parties and we expect this variable to be associated with a reduced probability of voting for a measure given the increased bargaining costs incurred. The federal deficit or surplus measure was obtained from the Budget of the United States Government, Fiscal Year 2012 Historical Tables. We utilize the current year’s surplus or deficit as a percentage of the gross domestic product measured in constant fiscal year 2000 dollars (Deficit). As the federal deficit increases, resources are more constrained and legislators are expected to be less likely to vote in favor of a measure. Summary statistics for all variables are provided in the Appendix. Estimation Strategy Because individual MCs vote on many bills over time in our sample, we are concerned about unobserved heterogeneity at the legislator level and use a statistical model that allows us to address the problem. We employ correlated random effects probit models (e.g., Mundlak 1978; Chamberlain 1982) to estimate the probability that an MC votes “yea” on a roll-call in our sample. The standard probit model with unobserved effects can be written as 𝑃(𝑦𝑖𝑡 = 1|𝑥𝑖𝑡 , 𝑢𝑖 ) = Φ(𝑥𝑖𝑡 + 𝑢𝑖 ). We follow the Chamberlain-Mundlak procedure in assuming that 𝑢𝑖𝑡 = 𝑥̅𝑖 + 𝑛𝑖 to relax the assumption of the independence of 𝑢𝑖 from 𝑥𝑖𝑡 . Practically speaking, then, we include time-averaged values of our independent variables, 𝑥̅𝑖 , as additional regressors in our models. We estimate these models separately on our samples of roll-call votes in the House and Senate. Our preferred specifications also control for unmodeled differences in legislative design within policy domains, thus we include fixed effects by policy domain. Our policy domain indicators rely on the Policy Agendas Projects coding of major topic of each of the laws and bills 12 included in the dataset. To further control for unobservables at the state level, we include state fixed effects as well. Results Our results regarding the influence of co-partisanship and GIA on the probability of members of Congress voting in favor of a measure on the floor are reported in Table 1.1 We provide a separate model for each chamber and, given the probit estimation and interacted variables, include a column for the marginal effect of increasing the grant ratio on the probability of voting “yea” across categories of co-partisanship to aid in interpretation. As expected, we find a negative marginal effect of increasing grants to the states for members who only match the partisanship of their president (Hypothesis 1) and a positive marginal effect for members who only match their governors (Hypothesis 2), all else in the model constant. Moreover, we also find support for hypotheses 3 and 4: members who match both executives’ party labels are less likely and those who match neither are more likely to vote for passage as the grant ratio increases. Specifically, the probability that a Democratic member of the House facing a Republican president, but with a Democratic governor will vote for passage increases by 35% as the grant ratio moves from zero grants in a legislative proposal up to a law that includes only grants to the states. A more reasonable interpretation would be to consider a measure that increases the ratio by 0.1—a law with 100 provisions would switch 10 provisions from centralizing with a federal agency to delegation to the states with GIA—this change would increase a gubernatorial copartisan’s probability of voting in favor by 3.5%. For presidential co-partisans who only match 1 This table utilizes the grant ratio in the final enactments, although analyses using House and Senate bill ratios are substantively similar. In effect, we are assuming House and Senate members estimate the extent to which the other chamber will influence the final ratio in these analyses. 13 the party of their president, though, this same change would result in an 8% lower probability of voting in favor of the measure. If we consider, instead, Republican members facing a Republican president we find support for our final two hypotheses in the House: members who match both executives (Full Co-Partisans) have a 5.8% lower likelihood and members who match neither (No Co-Partisans) have a 6% higher likelihood of voting “yea” on final passage. These differences in voting probabilities are statistically significant and the same patterns hold in the Senate: Gubernatorial co-partisans are 8.9% more likely, Presidential co-partisans 2.9% less likely, Full Co-partisans 4% less likely, and finally, No Co-partisans are 8.6% more likely to vote in favor of a measure that increases the grant ratio by 10%. In sum, we find support for all four of our hypotheses across both the House and Senate after controlling for individual-level legislator effects (through the Chamberlain-Mundlak mechanism), policy-specific differences (policy fixed effects), state-level differences (state fixed effects), as well as our other controls. The findings with respect to these final control variables also fit with our expectations and, for the most part, are similar across both chambers. For instance, we expected that a governor with the power to spend unanticipated federal funds would be a significant predictor of how national representatives would vote. Previous authors have found that most national laws include state implementation, thus a governor’s power vis-à-vis his legislature likely matters. We find this specific power increases the probability of House members voting in favor of a measure (10.6%), but has no statistically significant effect on Senator’s vote choices. As a state’s fiscal health improves, a member of either the House or the Senate is more likely to vote in favor of passage (6.9% for a 10% improvement in House and 7.2% in Senate), perhaps in order to claim credit for successes during the next election cycle. A divided legislature decreases the probability that a House member votes in favor of a measure 14 (11.1%), but the possibility of a null effect in the Senate cannot be rejected. An increasing federal deficit is associated with an increased likelihood of members in both chambers voting in favor of a measure (although this effect is small: 4.8% and 6% for a 1% increase in the deficit as a percentage of GDP). Finally, electoral cycles seem to matter in the Senate (positive and significant: 5.9%), but not in the House. Conclusion Our analysis is novel in that it relates the roll-call voting decisions of individual MCs to the characteristics of delegations. Specifically, we have examined the way in which the decentralization of implementation authority shapes those choices. Building our theoretical claims on the MCs expectation of oversight costs in maintaining their electoral constituency’s share of grant distributions, we hypothesize and find support for several claims. Ceteris paribus, members are less likely to vote for bills as their implementation becomes more decentralized through the inclusion of GIA provisions when they either share the party affiliation of the president, but not their home state’s governor or share partisan affiliation with both levels. MCs are more likely to vote in favor of bills as their implementation becomes more decentralized when they share partisanship with their home state governors, but not the president, all else equal. Finally, when members share party affiliation with neither of these political executives, the likelihood that they support a bill increases, ceteris paribus, with decentralization. 15 16 Figure 1: Average Congressional Choices by Congress in Final Enactments 1 0.9 0.7 0.6 Joint Ratio 0.5 Grant Ratio 0.4 0.3 State Ratio 0.2 National Ratio 0.1 0 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 Delegation Ratio 0.8 Congress 17 Figure 2: Chamber Differences in Average Grant Ratios by Congress 0.35 0.3 AVerage Grant Ratio 0.25 0.2 0.15 0.1 0.05 0 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 Congress Final Average Grant Ratio Senate Average of Grant Ratio House Average of Grant Ratio 18 Table 1: Congressional Vote Choices & Grants-in-Aid House Passage Variables House Average Marginal Effects Senate Passage Match Governor baseline Match President 0.162 Avg M.E. -0.017 0.419 (0.038)** (0.036) (0.084)** Match Both Match Neither Grant Ratio Match Governor x Grant Ratio baseline Avg M.E. (0.133)** 0.234 (0.084)** 0.230 (0.096)* -0.174 (0.054**) 0.525 (0.078)** baseline M.E. ↑GIA 0.894 0.186 0.039 0.431 (0.036)** (0.034) (0.099)** -0.322 -0.283 -0.167 (0.035)** (0.032)** (0.057)** 0.350 0.128 (0.001) M.E. ↑GIA 0.350 (0.063)** baseline 0.894 (0.063)* Match President x Grant Ratio Match Both x Grant Ratio Match Neither x Grant Ratio Gubernatorial Spending Power State Fiscal Health Divided Legislature Federal Deficit (as % GDP) Election Year Senate Average Marginal Effects (0.133)* -1.147 -0.798 -1.188 -0.294 (0.088)** (0.067)* (0.191)** (0.142)^ -0.934 -0.584 -1.291 -0.397 (0.084)** (0.063)* (0.198)** (0.158)^ 0.248 0.598 -0.039 0.855 (0.078)** (0.058)* (0.153) (0.108)* 0.106 0.106 0.072 0.072 (0.046)* (0.046)* (0.086) (0.086) 0.690 0.690 0.608 0.608 (0.051)** (0.051)** (0.134)** (0.134)** -0.111 -0.111 0.011 0.011 (0.016)** (0.016)** (0.053) (0.053) 0.048 0.048 0.060 0.060 (0.007)** (0.007)** (0.013)** (0.013)** 0.006 0.006 0.059 0.0588 (0.011) (0.011) (0.029)* (0.029)* Grant Ratio 0.114 0.114 0.087 0.087 (averaged, by legislator) (0.407) (0.407) (0.845) (0.845) Match with President -0.405 -0.405 -0.433 -0.433 (averaged, by legislator) (0.039)** (0.039)** (0.104)** (0.104)** Match with Governor -0.103 -0.103 0.091 0.091 (averaged, by legislator) (0.042)* (0.042)* (0.089) (0.089) Gubernatorial Power -0.107 -0.107 -0.145 -0.145 (averaged, by legislator) (0.067) (0.067) (0.142) (0.142) State Fiscal Health 0.358 0.358 -0.079 -0.079 (0.588) (averaged, by legislator) (0.357) (0.357) (0.588) Divided Legislature -0.018 -0.018 0.103 0.103 (averaged, by legislator) (0.078) (0.078) (0.171) (0.171) Federal Deficit (averaged, by legislator) Election Year 0.031 0.031 -0.049 -0.049 (0.014)* (0.014)* (0.030) (0.030) 0.590 0.590 -0.173 -0.173 19 (averaged, by legislator) Policy Area Fixed Effects State Fixed Effects Constant N Wald AIC BIC (0.234)* (0.234)* (0.399) (0.399) Results not shown here, reported in Appendix Results not shown here, reported in Appendix 0.754 0.798 (0.172)** (0.288)** 68,324 3,640.04 68559.63 69372.38 14,299 704.18 12992.52 13666.07 Mundlak-Chamberlain corrected random effects probit, including fixed effects for state and policy area with robust s.e. where ^ p<0.1; * p<0.05; ** p<0.01. 20 References Albouy, David. 2008. “Partisan Representation in Congress and the Geographic Distribution of Federal Funds.” University of Michigan, Department of Economics. Working paper. Aldrich, John H. 1995. Why Parties? The Origin and Transformation of Parties in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Ansolabehere S, Snyder JM, and Ting MM. 2003. “Bargaining in Bicameral Legislatures: When and Why Does Malapportionment Matter?” American Political Science Review, 97(3):471-481. Anton, TJ. 1997. “New Federalism and Intergovernmental Fiscal Relationships: Implications for Health Policy,” Journal of Health Politics, Policy, and Law 22(3):691-720. Arnold R Douglas. 1990. The Logic of Congressional Action. New Haven, Yale University Press. Baron DP and Ferejohn JA. 1989. “Bargaining in Legislatures,” The American Political Science Review, 83(4):1181-1206. Baumgartner, Frank R and Bryan D. Jones. 1993. Agendas and Instability in American Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Baumgartner, Frank R., and Bryan D. Jones. 2015. The Politics of Information. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Berry, Burden and Howell. 2010. “The President and the Distribution of Federal Spending,” APSR. 104(4):783-99. Bertelli, Anthony M., and Grose, Christian R.. 2009. “Secretaries of Pork? A New Theory of Distributive Public Policy.”Journal of Politics. 71: 926–4 Boadway and Shah, 2009. Fiscal Federalism: Principles and Practice of Multiorder Governance. Cambridge University Press. Calvert and Weingast. 1982. “Runaway Bureaucracy and Congressional Oversight: Why Reforms Fail,” Review of Policy Research 1(3):557-564. Chamberlain, Gary. 1982. “Multivariate regression models for panel data.” Journal of Econometrics 18(1): 5-46. Chubb, JE. "The Political Economy of Federalism." APSR 79(4):994-1015, 1985. Collingwood, Loren and John Wilkerson. “Tradeoffs in Accuracy and Efficiency in Supervised Learning Methods.” Journal of Information Technology and Politics, 9:3 (2012). 21 Cox GW and McCubbins MD. 2005. Setting the Agenda: Responsible Party Government in the US House of Representatives. Cambridge University Press, 2005. Crespin, Finocchiaro, and Wanless 2009 “Perception and Reality in Congressional Earmarks,” The Forum 7(2). Dixit, Avinash K. 1998. The making of economic policy: a transaction-cost politics perspective. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Doyle, Richard. 2011. “Real Reform or Change for Chumps: Earmark Policy Developments 2006-2010,” Public Administration Review 71(1). Enns Peter and Julianna Koch. 2013. “Public Opinion in the U.S. States 1956-2010.” State Politics and Policy Quarterly 13(3):349-372. Epstein, David and Sharon O’Halloran. 1999. Delegating Powers: a Transaction Cost Politics Approach to Policy Making Under Separate Powers. Cambridge U.K.: Cambridge University Press. Evans, Diana. 2004. Greasing the Wheels: Using Pork Barrel Projects to Build Majority Coalitions in Congress. New York: Cambridge University Press Gray Virginia & Lowery David. 2000. The population ecology of interest representation: Lobbying communities in the American states. University of Michigan Press. Grogan, Colleen M., and Elizabeth Rigby. 2009. Federalism, partisan politics, and shifting support for state flexibility: The case of the U.S. State Children’s Health Insurance Program.Publius: The Journal of Federalism 39(1): 47-69. Grose, Christian R. 2011. Congress In Black And White: Race And Representation In Washington And At Home. New York: Cambridge University Press. Hall, Richard L. 1996 Connecticut. Particpation in Congress, Yale University Press, New Haven, Holbrook Thomas M and Emily Van dunk. 1993. “Electoral Competition in the American States,” APSR 87(4):955-962. Jurka, Tim, Loren Collingwood, Amber Boydstun, Emiliano Grossman, and Wouter van Atteveldt. 2013. “RTextTools: A Supervised Learning Package for Text Classification in R” The R Journal. 5:1. Inman, Robert P., "Federal Assistance and Local Services in the United States: The Evolution of a New Federalist Fiscal Order" (February 1989). NBER Working Paper No. W2283. Accessed at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=347056 December, 2006. Inman RP and Rubinfeld DL. 1996. "Designing Tax Policies in Federalist Economies: An Overview" Jnl of Public Econ 60:307-34. 22 Johnson Kimberly S. 2007. Governing the American State: Congress and the New Federalism, 1877–1929.(Princeton Studies in American Politics.) Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Koenig, Louis W. 1938. “Federal and State Cooperation under the Constitution,” Michigan Law Review, Vol. 36, No. 5 (Mar., 1938), pp. 752-85. Kiewiet, Roderick, and McCubbins, Matthew. 1988. “Presidential Influence on Congressional Appropriations Decisions.”‘American Journal of Political Science 32: 713–36 Knight Brian. 2008. Legislative Representation and the Distribution of Federal Funds: Evidence form the US Congress. The Economic Journal 118: 1785-1803. Krupnikov, Yanna and Charles Shipan. 2012. “Gubernatorial Budgetary Power Scores: A New Approach” State Politics and Policy Quarterly12(4):438-455. Larcinese, Valentino, Rizzo, Leonzio, and Testa, Cecilia. 2006. “Allocating the U.S. Federal Budget to the States: The Impact of the President.” Journal of Politics 68: 447–56Dixit and Londregan 2006 Lazarus, J. 2010. “Giving the People What They Want? The Distribution of Earmarks in the US House of Representatives,” AJPS 54(2). Lee FE. 2000. “Senate Representation and Coalition Building in Distributive Politics,” American Political Science Review 94(1):59-72. Levitt S. and Poterba, J. (1999). _Congressional distributive politics and state economic performance_, Public Choice, vol. 99 (April), pp. 185–216 Macey, Jonathan R. 1992. “Organizational design and political control of administrative agencies.” Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization 8 (1): 93-. Mayhew, David. 2005. Divided We Govern. New Haven: Yale University Press. Mayhew, David. “Datasets.” govern/, (Sept 6, 2011). http://davidmayhew.commons.yale.edu/datasets-divided-we- McCann, Pamela J. Clouser. 2015a. The Federal Design Dilemma: Congress and Intergovernmental Delegation, manuscript, University of Southern California. McCubbins MD and Schwartz T. 1984. “Congressional Oversight Overlooked: Police Patrols versus Fire Alarms,” American Journal of Political Science, 28:165–179. McCubbins MD, Noll RG, and Weingast BR. 1989. “Structure and Process, Politics and Policy: Administrative Arrangements and the Political Control of Agencies.” Virginia Law Review, 75(March):431–82. Mundlak, Yair. 1978. “On the pooling of time series and cross section data.” Econometrica 46(1): 69-85. 23 Nathan, Richard P and Thomas L Gais. 2001. “Is Devolution Working? Federal and State Roles in Welfare,” Brookings Institute Newsletter Research Article, Summer 2001. Nathan, Richard P. 1987. “The Politics of Printouts: The Use of Official Numbers to Allocate Federal Grants-in Aid,” in William Alonso and Paul Starr’s The Politics of Numbers, Russell Sage Foundation. p 331. Nathan RP. 1983. "State and Local Governments under Federal Grants: Toward a Predictive Theory." Pol Sci Quarterly 98(1):47-57. Nicholson-Crotty, Sean. 2012. “Leaving Money on the Table: Learning from Recent Refusals of Federal Grants in the American States.” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 42: 449-466. Oates, WE. 1999. "An Essay on Fiscal Federalism." Jnl of Econ Lit. 37(3):1120-49. Oates, WE. 2005 “Toward and Second Generation Theory of Fiscal Federalism.” Internat Tax and Pub Fin 12:349-73. Papke LE and Woolridge JM. 1996. “Econometric Methods for Fractional Response Variables With an Application of 401(K) Plan Participation Rates.” Journal of Applied Econometrics 11(6):619-632. Peterson, PE. 1995. The Price of Federalism. Brookings Institution, Washington D.C.. Posner, PL. 1988. The Politics of Unfunded Mandates: Whither Federalism? University Press, Washington D.C. Georgetown Rabe, BG. 1999. "Federalism and Entrepreneurship: Explaining American and Canadian Innovation in Pollution Prevention and Regulatory Integration." Policy Studies Jnl. 27(2):288306. Ranney,Austin. 1976. “Parties in State Politics.” In Politics in the American States, 3rd ed., eds. Herbert Jacob and Kenneth Vines. Boston, MA: Little, Brown. Rodden, Jonathan A. 2006. Hamilton’s Paradox. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, New York. Schattschneider EE. 1975. Semi-sovereign People: A Realist’s View of Democracy in America. Fort Worth, Texas, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers. Sin, G. and A. Lupia. 2008. “How the Senate and President Affect the Balance of Power in the House: A Constitutional Theory of Intra-chamber Bargaining.” Manuscript. Stein, Robert M., and Kenneth N. Bickers. 1994. Congressional Elections and the Pork Barrel. Journal of Politics 56: 377-399 Ting, Michael. 106(2):367-385. 2012 “Legislatures, Bureaucracies, and Distributive Spending,” APSR 24 U.S. Congressional Research Service. "Federal Grants to State and Local Governments: A Brief History" Report for Congress, February, 2003. Accessed at http://usinfo.state.gov/usa/infousa/politics/states/fedgrants.pdf December, 2006. U.S. General Accounting Office. 2006. "Federal Grants: Design Improvements Could Help Federal Resources Go Further" Report to the Chairman, Committee on the Budget, House of Representatives, December, 1996. Accessed at http://www.gao.gov/archive/1997/ai97007.pdf. Volden C. 2005. “Intergovernmental Political Competition in American Federalism.” American Journal of Political Science 49(2): 327-342. Volden C. 2007. “Intergovernmental Grants: A Formal Model of Interrelated National and Subnational Political Decisions,” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 37(2):209-243. Zimmerman, JF. "The Nature and Political Significance of Preemption." PS: Political Science and Politics 38:359-62, 2005. Zipay, Keith P. 2013. “Government Receipts and Expenditures, Third Quarter of 2013” Bureau of Economic Analysis Survey of Current Business. December 2013 pp11-13. http://www.bea.gov/scb/pdf/2012/09%20September/0912_gre.pdf 25 Appendix Table 1A: Summary Statistics Continuous Variables Grant Ratio State Fiscal Health (lag) Federal Deficit as a % of GDP Categorical Variables Votes Copartisan Regime Gubernatorial Power Divided Legislature Election Year Legislator Specific Averages: Gubernatorial Power State Fiscal Health (1 year lag) Divided Legislature Federal Deficit as a % of GDP Election Year Legislator-to-President Distance Legislator-to-Governor Distance Grant Ratio Continuous Variables Grant Ratio State Fiscal Health (1 year lag) Federal Deficit as a % of GDP Categorical Variables Votes Copartisan Regime Gubernatorial Power Divided Legislature Election Year Legislator Specific Averages: Gubernatorial Power State Fiscal Health (1 year lag) Divided Legislature Federal Deficit as a % of GDP Election Year Legislator-to-President Distance Legislator-to-Governor Distance Grant Ratio House Final Enactments N Mean 79002 0.160 79824 0.087 2.131 0.5 69214 79828 79744 79828 79828 N 79824 79824 79828 79828 79828 -2.666 0's 16263 30418 36160 65899 34056 Mean 0.495 0.087 0.174 -2.666 0.573 s.d. 0.411 0.038 0.137 0.990 0.057 min 0.000 -0.617 10.100 1's 52951 11870 35390 13929 45772 min 0.000 -0.332 0.000 -9.775 0.000 79828 0.293 0.357 0.000 1.000 79828 0.526 79828 0.160 Senate Final Enactments N Mean 17381 0.161 17578 0.085 0.315 0.026 0.000 0.026 1.000 0.354 s.d. 0.186 0.133 max 0.786 1.236 17578 0's 2801 6758 5716 14785 7064 N 17532 17578 17578 17578 17578 -2.731 0.5 2430 5486 Mean 0.610 0.085 0.160 -2.731 0.598 2.105 1's 11827 2904 9664 2820 10514 s.d. 0.396 0.041 0.132 0.904 0.055 min 0.000 -0.617 10.100 2's min 0.000 -0.102 0.000 -9.667 0.000 max 1.000 0.283 1.000 0.525 1.000 17578 0.303 0.346 0.000 1.000 17578 17578 0.523 0.161 0.316 0.022 0.000 0.013 1.000 0.321 79828 2043 s.d. 0.188 0.119 8194 max 0.786 1.236 2.400 2's 11538 max 1.000 0.347 1.000 2.400 1.000 2.400 3's 26 Table 2a: Congressional Vote Choices & Grants-in-Aid (State & Policy Fixed Effects Reported) Variables House Passage House Passage Full Senate Passage Senate Passage Full Match Governor Match President baseline 0.176 baseline 0.162 baseline 0.428 baseline 0.419 (0.028)** (0.038)** (0.061)** (0.084)** 0.209 0.186 0.467 0.431 (0.027)** (0.036)** (0.063)** (0.099)** -0.299 -0.322 -0.143 -0.167 (0.020)** (0.035)** (0.044)** (0.057)** 0.127 0.350 0.972 0.894 (0.053)* (0.063)** (0.128)** (0.133)** baseline -1.086 baseline -1.147 baseline -1.138 baseline -1.188 (0.088)** (0.088)** (0.203)** (0.191)** -0.893 -0.934 -1.288 -1.291 (0.088)** (0.084)** (0.214)** (0.198)** 0.224 0.248 -0.104 -0.039 (0.076)** (0.078)** (0.185) (0.153) Match Both Match Neither Grant Ratio Match Governor x Grant Ratio Match President x Grant Ratio Match Both x Grant Ratio Match Neither x Grant Ratio Gubernatorial Spending Power 0.106 0.072 (0.046)* (0.086) 0.690 0.608 (0.051)** (0.134)** -0.111 0.011 (0.016)** (0.053) Federal Deficit 0.048 0.060 (as % GDP) (0.007)** (0.013)** Election Year 0.006 0.059 (0.011) (0.029)* State Fiscal Health Divided Legislature Grant Ratio 0.902 0.114 0.937 0.087 (averaged, by legislator) (0.358)* (0.407) (0.896) (0.845) Match with President -0.399 -0.405 -0.496 -0.433 (averaged, by legislator) (0.035)** (0.039)** (0.078)** (0.104)** Match with Governor -0.120 -0.103 0.005 0.091 (averaged, by legislator) (0.035)** (0.042)* (0.078) (0.089) Gubernatorial Power -0.107 -0.145 (averaged, by legislator) (0.067) (0.142) State Fiscal Health 0.358 -0.079 (averaged, by legislator) (0.357) (0.588) Divided Legislature -0.018 0.103 (averaged, by legislator) (0.078) (0.171) Federal Deficit 0.031 -0.049 (averaged, by legislator) (0.014)* (0.030) Election Year 0.590 -0.173 (averaged, by legislator) (0.234)* (0.399) Macroeconomics baseline baseline 27 Civil Rights Health Agriculture Labor/Employment Education Environment Energy Transportation Law/Crime Social Welfare Community Development/Housing Banking/Finance/Domestic Commerce Defense Space/Science/Technology/Communications Foreign Trade International Affairs/Foreign Aid Government Operations Public Lands/Water Management Connecticut Maine Massachusetts New Hampshire Rhode Island Vermont Delaware New Jersey New York Pennsylvania Illinois Indiana Michigan Ohio 0.404 (0.035)** -0.020 (0.026) -0.126 (0.035)** 0.236 (0.025)** -0.105 (0.023)** 0.896 (0.032)** 0.200 (0.026)** 0.265 (0.032)** 0.574 (0.041)** -0.216 (0.034)** 0.045 (0.028) 0.669 (0.024)** 0.580 (0.023)** 0.016 (0.041) 0.106 (0.043)* -0.405 (0.064)** 0.265 (0.021)** 0.273 (0.038)** baseline -0.120 (0.156) -0.254 (0.106)* -0.172 (0.185) -0.233 (0.137)^ -0.064 (0.352) 0.049 (0.182) -0.049 (0.107) -0.080 (0.095) -0.096 (0.103) -0.198 (0.102)^ -0.056 (0.114) -0.155 (0.107) -0.225 0.437 (0.070)** 0.438 (0.078)** 0.035 (0.096) 0.519 (0.058)** 0.040 (0.057) 0.544 (0.062)** 0.271 (0.055)** 0.283 (0.072)** 0.610 (0.081)** 0.493 (0.086)** 0.417 (0.081)** 0.461 (0.059)** 0.590 (0.070)** 0.260 (0.081)** 1.087 (0.139)** 0.445 (0.124)** 0.269 (0.045)** 0.835 (0.104)** baseline 0.082 (0.133) -0.118 (0.155) -0.368 (0.222)^ -0.050 (0.214) 0.110 (0.263) -0.159 (0.107) -0.186 (0.166) -0.223 (0.197) 0.694 (0.151)** -0.162 (0.169) -0.042 (0.143) -0.076 (0.185) -0.052 28 Wisconsin Iowa Kansas Minnesota Montana Nebraska North Dakota South Dakota Virginia Alabama Arkansas Florida Georgia Louisiana Mississippi North Carolina South Carolina Texas Kentucky Maryland Oklahoma Tennessee West Virginia Arizona Colorado Idaho Montana Nevada New Mexico Utah Wyoming (0.102)* -0.237 (0.114)* 0.032 (0.136) -0.137 (0.125) -0.221 (0.123)^ -0.215 (0.112)^ -0.130 (0.146) -0.207 (0.094)* -0.140 (0.175) -0.322 (0.096)** -0.224 (0.110)* -0.210 (0.118)^ -0.206 (0.098)* -0.298 (0.108)** -0.380 (0.132)** -0.275 (0.121)* -0.073 (0.105) -0.192 (0.103)^ -0.453 (0.095)** -0.146 (0.109) -0.224 (0.111)* -0.373 (0.115)** -0.087 (0.118) -0.149 (0.154) -0.502 (0.141)** -0.404 (0.127)** -0.531 (0.189)** -0.414 (0.188)* -0.023 (0.178) -0.228 (0.160) -0.186 (0.148) -0.435 (0.128) -0.424 (0.187)* -0.007 (0.112) -0.057 (0.130) 0.019 (0.140) 0.251 (0.131)^ -0.415 (0.149)** -0.010 (0.128) -0.204 (0.191) -0.139 (0.246) -0.349 (0.122)** -0.300 (0.148)* -0.311 (0.140)* -0.220 (0.121)^ -0.217 (0.160) -0.440 (0.158)** -0.599 (0.211)** -0.574 (0.186)** -0.341 (0.224) -0.099 (0.094) -0.061 (0.174) -0.587 (0.156)** 0.032 (0.222) -0.161 (0.143) -0.672 (0.182)** -0.224 (0.164) -0.588 (0.188)** -0.189 (0.104)^ -0.305 (0.178)^ -0.089 (0.154) -0.485 (0.200)* -0.329 29 (0.203)* -0.285 (0.098)** -0.231 (0.146) -0.079 (0.107) -0.028 (0.090) -0.036 (0.220) California Oregon Washington Alaska Hawaii Constant N Wald AIC BIC (0.212) -0.128 (0.155) 0.035 (0.236) -0.077 (0.177) 0.105 (0.175) -0.158 (0.132) 0.888 0.754 0.768 0.798 (0.063)** (0.172)** (0.159)** (0.288)** 68,388 759.31 71629.39 71738.99 68,324 3,640.04 68559.63 69372.38 14,431 210.12 13458.55 13549.47 14,299 704.18 12992.52 13666.07 Mundlak-Chamberlain corrected random effects probit, including fixed effects for state and policy area with robust s.e. where ^ p<0.1; * p<0.05; ** p<0.01. 30