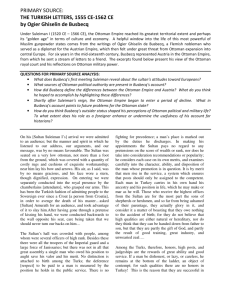

Comparison of Turkish and Christian Soldiers

advertisement

1 Primary Source 4.6 OGIER GHISELIN DE BUSBECQ, TURKISH LETTERS (1581)1 The Turkish Ottoman Empire expanded steadily throughout the Middle East and into southeastern Europe after its founding in 1299 by Osman I (1258–1326). Probably its most important conquest was the capture in 1453 of Constantinople, thanks to diverse military strategies and massive cannon, thus overthrowing the Byzantine Empire. The most important force of the Ottoman military was the Janissary Corps, the Ottoman Sultan’s bodyguards. This force, recruited from children of captured Christian slaves, consisted in infantry (foot soldiers) who bore firearms—a result of the Eurasia-wide Gunpowder Revolution. The Janissaries, as household slaves of the sultan, were utterly beholden (they could not even marry until the law changed in 1572) and therefore completely loyal to him. Despite impressive military successes during several centuries, by the last 1700s the Ottoman Empire fell into decline and was overtaken by the major European nations in military strength. By the late 1500s, the corps numbers roughly 14,000. The following is a description of the Ottoman military forces and a brief comparison of Christian forces. The passage is taken from a lengthy account of the Ottoman Empire, published in the form of letters written by Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq (1522–92), a Flemish author and the ambassador of the Holy Roman Empire to the Ottoman Empire from 1554 to 1562. Busbecq’s ambassadorship coincided with the rule of the greatest Ottoman sultan, Suleiman I the Magnificent (r. 1520–66). This was also the high point of Ottoman power, which gradually encroached on the lands of the Holy Roman Empire and culminated in the first siege of Vienna in 1529 (the second siege, in 1683, probably marked the onset of Ottoman military decline). Busbecq’s depiction of the Janissaries valor—though not of their military equipment—is highly favorable. The excerpt below and volume one of the letters, which remain an important source concerning the Ottoman court during the mid-1500s, can be found here. ... The Turkish monarch going to war takes with him over 40,000 camels and nearly as many baggage mules, of which a great part, when he is invading Persia, are loaded with rice and other kinds of grain. These mules and camels also serve to carry tents and armour, and likewise tools and munitions for the campaign. The territories, which bear the name of Persia, and are ruled by the Sophi, or Kizilbash 2 as the Turks call him, are less fertile than our country, and even such crops as they bear are laid waste by the inhabitants in time of invasion in hopes of starving out the enemy, so that it is very dangerous for an army to invade Persia, if it be not furnished with abundant supplies. The invading army carefully abstains from encroaching on its magazines at the outset; as they are well aware that, when the season for campaigning draws to a close, they will have to retreat over districts wasted by the enemy, or scraped as bare by countless hordes of men and droves of baggage animals, as if they had been devastated by locusts; accordingly they reserve their stores as Charles Foster and F. H. Daniel (eds.), The Life and Letters of Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq, 2 vols. (London: C. Kegan Paul and Co., 1881), 1:219–223. 2 A label given to militant Shiite groups located in regions of the Ottoman Empire. 1 2 much as possible for this emergency. Then the Sultan’s magazines are opened, and a ration just sufficient to sustain life is daily weighed out to the Janissaries and other troops of the royal household. The rest of the army are badly off, unless they have provided some supplies at their own expense. And this is generally the case, for the greater number, and especially the cavalry, having from their long experience in war already felt such inconveniences, lead with them a sumpter3 horse by a halter, on which they carry many of the necessaries of life; namely, a small piece of canvas which they use as a tent, for protection against sun and rain, with the addition of some clothes and bedding; and as provisions for their private use, a leathern bag or two of the finest flour, with a small pot of butter, and some spices and salt, on which they sustain life when they are hard pressed. On such occasions they take out a few spoonfuls of flour and put them into water, adding some butter, and seasoning the mess with salt and spices; these ingredients are boiled, and a large bowl of gruel is thus obtained. Of this they eat once or twice a day, according to the quantity they have, without any bread, unless they have brought some biscuit with them. In this way they are able to support themselves from their own supplies for a month, or if necessary longer. Some fill a bladder with beef, dried and reduced to powder, which forms a highly nutritious food and expands greatly in the cooking, like the flour of which I spoke above. Sometimes too they have recourse to horseflesh; dead horses are of course plentiful in their great hosts, and such beasts as are in good condition when they die furnish a meal not to be despised by famished soldiers, I must not forget to tell you of the men who have lost their horses. When the Sultan moves his camp they stand in a long line by the side of the road with their saddles on their heads, as a sign that they have lost their steeds and need assistance for the purchase of others. An allowance is then made to them by the Sultan at his discretion. From this you will see that it is the patience, self-denial, and thrift of the Turkish soldier that enable him to face the most trying circumstances, and come safely out of the dangers that surround him. What a contrast to our men! Christian soldiers on a campaign refuse to put up with their ordinary food, and call for thrushes, becaficos, 4 and such like dainty dishes! If these are not supplied they grow mutinous and work their own ruin; and, if they are supplied, they are ruined all the same. For each man is his own worst enemy, and has no foe more deadly than his own intemperance, which is sure to kill him, if the enemy be not quick. It makes me shudder to think of what the result of a struggle between such different systems must be; one of us must prevail and the other be destroyed, at any rate we cannot both exist in safety. On their side is the vast wealth of their empire, unimpaired resources, experience and practice in arms, a veteran soldiery, an uninterrupted series of victories, readiness to endure hardships, union, order, discipline, thrift, and watchfulness. On ours are found an empty exchequer, luxurious habits, exhausted resources, broken spirits, a raw and insubordinate soldiery, and greedy generals; there is no regard for discipline, license runs riot, the men indulge in drunkenness and debauchery, and, worst of all, the enemy are accustomed to victory, we, to defeat. Can we doubt what the result must be? The only obstacle is Persia, whose position on his rear forces the invader to take precautions. The fear of Persia gives us a respite, but it is only for a time. When he has secured himself in that quarter, he will fall upon us with all the resources of the East. How 3 4 A pack animal, such as a horse or a mule. A small songbird. 3 ill prepared we are to meet such an attack it is not for me to say. I now return to the point from which I made this digression. I mentioned that baggage animals are used in a campaign for carrying armour and tents. These for the most part belong to the Janissaries. The Turks take great care to have their soldiers in good health and protected against the inclemency of the weather. They must defend themselves from the enemy, for their health the State will undertake to provide. Therefore you may see a Turk better clad than armed. They are especially afraid of cold, and even in summertime wear three garments, of which the innermost one, or shirt, is woven of coarse thread and gives a great deal of warmth. For protection against cold and rain they are furnished with tents, in which each man is given just room enough for his body, so that one tent holds twenty-five or thirty Janissaries. The cloth for the clothes I referred to is supplied by the State, and is distributed after the following fashion. The soldiers at nightfall are summoned by companies to the office for the distribution of such stores, where parcels of cloth are ready in separate packets according to the number of men in each company. They march in, and take their chance in the dark, so that if any soldier’s cloth is of inferior quality to that of his comrades, he has nought to grumble at save his own bad luck. For the same reason their pay is not given them by tale, but by weight, to prevent anyone accusing the paymaster of giving him light or clipped coins. Moreover, their pay is always given them the day before it is actually due. The convoy of armour, of which I spoke, is intended chiefly for the use of the royal horse-guards, as the Janissaries are lightly equipped, and generally do not fight at close quarters, but at a distance with muskets. Well, when the enemy is near, and a battle is expected, the stock of armour is produced, consisting for the most part of antiquated pieces picked up on the fields which have been the scene of Turkish victories; they are distributed to the royal horse guards, who at other times have only their light shield to protect them. Where so little pains is taken to provide each man with a suit that fits him, I need hardly tell you that they are but clumsily equipped. One man’s cuirass is too tight, another’s helmet too big; a third gets a coat of mail too heavy for him to bear; one way or another no one is properly accoutred.5 Yet they never grumble, holding that a man who quarrels with his armour must needs be a cowardly fellow, and are confident that they will make a stout fight of it themselves whatever their equipment may be. This feeling is the result of their great successes and military experience. In the same spirit they do not hesitate to turn their veteran infantry, who never have fought on horseback, into cavalry, for they are firmly convinced that a man who has courage and military experience will do brave service in whatever kind of fighting he may be engaged. ... 5 Provided with equipment or dress.