Astro 160: The Physics of Stars

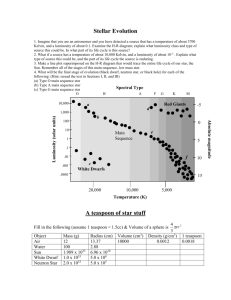

advertisement