Supplement

advertisement

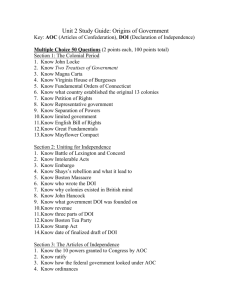

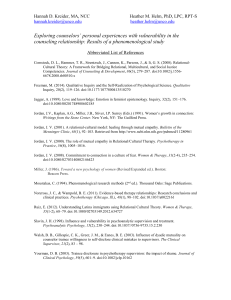

www.sciencemag.org/content/345/6192/1236828/suppl/DC1 Supplementary Materials for Evolution of Early Homo: An Integrated Biological Perspective Susan C. Antón, Richard Potts, Leslie C. Aiello E-mail: susan.anton@nyu.edu (S.C.A.); pottsr@si.edu (R.P.); laiello@wennergren.org (L.C.A.) Published 4 July 2014, Science 345, 1236828 (2014) DOI: 10.1126/science.1236828 This PDF file includes: Supplementary Text Tables S1 and S2 References Supplementary Text Early Homo Groups: Anatomy and Constituents The main specimens we include in each early Homo group are listed in Table S1. Group characteristics and ranges of body, brain and dental size can be found in text Table 1 and Box 1. Here we provide additional detail on the specific features used to recognize and affiliate key fossils to particular groups or to differentiate among groups. For the purposes of this review we focus on the fossil record from about 2.5 to about 1.5 million years ago. Earliest fossil Homo: Earliest fossil Homo is identified relative to late Australopithecus by reduced tooth and jaw size and shape and reorganization of the palate. Later early Homo groups reveal that there are a variety of ways in which this reorganization takes place. In the case of the early (~2.33 Ma) palate A.L. 666-1 from Hadar, molar size reduction, small canine root size, a relatively deep palate and posterior dental arches that are broad, parabolic and not parallel are key features (33). Time based on East African remains: >2.1 million years ago 1470 group: Affiliations to the 1470 group start with the face of KNM-ER 1470, which is anatomically similar to but much larger than the partial face, KNM-ER 62000. The shape of the palate and arcade of KNM-ER 1470 and KNM-ER 62000 link them to mandible KNM-ER 60000. Mandibular features and dental proportions link KNM-ER 60000 with KNM-ER 1482. Arcade shape definitively excludes KNM-ER 1802 and the morphologically similar Uraha 501, from Malawi, from this group (5). Facial Shape: The facial skeleton is fairly derived but not specifically in the direction of later Homo. The anterior face is flat, a feature that is independent of hafting. Contributing to this flatness, the incisor and canine row is flat/squared-off and the zygomatic processes arise relatively far forward on the face. The nasals are peaked. The face is relatively tall, and related to this, the broad mandibular ramus (as represented by KNM-ER 60000) sits quite high above the tooth row. The mandibular corpus is relatively tall compared to width and the posterior mandible is much broader (bigonial/bicondylar) than the anterior in part as a result of diverging posterior tooth rows. As a result, the extramolar sulcus is broad. Dentition: Lower incisor crowns are narrow with relatively short roots and the canine root is also reduced in size compared to Australopithecus. The posterior tooth row is relatively short due to premolar foreshortening not to molar reduction. Premolars are relatively mesiodistally compressed and are not unduly molarized, but molars are large. There is no third molar reduction. While Table 1 may suggest that the 1470 group has larger molar occlusal areas than the 1813 group, dental size is not absolutely large in the 1470 group with respect to other non-erectus Homo. Apparent difference in molar size is most likely an artifact of excluding specimens such as KNM-ER 1802, KNM-ER 1590 and OH 16 from both groups in favor of putting them in an unaffiliated non-erectus category. However, KNM-ER 1802 cannot be placed with the 1470 group and we 2 suspect belongs to the 1813 group (see below). Such placement would obviate most molar size differences. Vault: Vault anatomy is preserved only in the largest specimen, KNM-ER 1470 (41). The vault is relatively rounded in sagittal view with a steeply rising frontal lacking a supratoral gutter. There is moderate postorbital constriction. No sagittal or nuchal cresting is apparent. Greatest breadth is at the supramastoid crest region, but the vault walls rise nearly vertical from supramastoid gutter rather than angling medially and thus greatest parietal breadth is only a bit smaller than greatest breadth. Size: Both body and brain size estimates in Table 1 are skewed to the larger end of the assemblage because only the largest specimen, KNM-ER 1470, preserves cranial capacity and orbit size (from which body mass may be estimated). However, the fragmentary remains affiliated with one another based on palate shape display a range of size variation in which KNM-ER 1470 is the largest and KNM-ER 62000 the smallest (at only about 75-80% of KNM-ER 1470’s size). Estimates of the body and brain size range of this group suggested by these fragments is, therefore, extensive and overlaps substantially with the 1813 group (see details in Box 1). Postcrania: Postcranial traits and proportions are unknown given the current lack of affiliated postcranial remains. Time based on East African remains: 2.09-1.78 million years ago The 1813 group Affiliations start from the face of 1813, which is anatomically similar to that of OH 13 and KNM-ER 1805, both of which also retain a mandible. The anterior palate of 1813 also links to the OH 65 palate – however, the latter specimen is substantially larger with some shape differences and scaling studies may indicate whether these are of importance when additional specimens are available. Unlike the 1470 group, mandibular/arcade shape is consistent with that of KNM-ER 1802 and UR 501; however, because this shape is relatively primitive this consistency does not dictate identity. Nonetheless, the most parsimonious explanation would be that there are two groups of non-erectus early Homo and that KNM-ER 1802 and Uraha 501 affiliate with the 1813 group. Facial Shape: The facial skeleton is fairly primitive and relatively prognathic compared to the 1470 group. The anterior palate is rounded and more projecting (the incisors and canines do not form a flat row across the front of the palate) and the posterior tooth rows are more parallel (less diverging) and relatively narrow (5). However, the face lacks features seen in the face of Australopithecus including facial pillars and a glabellar prominence and while more prognathic than the 1470 group is less so than Australopithecus (41). Additionally, the nasals are more peaked. The mandibles of the 1813 group also tend to have corpora that are more similar in their height and width than the 1470 group, which tends to have fairly tall corpus heights for width. While no complete rami are present, the partial rami would suggest that the extramolar sulcus is not as broad and probably that the bicondylar/bicoronoid breadths are not as great compared to arcade breadth as in the 1470 group, which would also partly follow from the more parallel and narrow posterior arcades. Dentition: Anterior dental size is somewhat more primitive than the 1470 group with larger lower incisor crowns and canine roots. There is no third molar occlusal area 3 reduction. Although Tables 1 and S2 show that some specimens have smaller M1s than KNM-62000 of the 1470 group, the apparent differences in group means/ranges are likely an artifact of specimen inclusion (see discussion of KNM-ER 1802 above). Molar and premolar size is reduced relative to the condition in Australopithecus. Vault and Base: The vault is rounded in sagittal view with a frontal that shows a continuous posttoral sulcus. There is moderate postorbital constriction. Cresting is apparent in some individuals. Greatest breadth is low in the supramastoid region, but the greatest breadth at the parietals is only marginally smaller. The cranial base is shorter than in Australopithecus and the mandibular fossa is more derived than that genus, but both lack the specific traits of H. erectus. Size: Both body and brain size estimates in Table 1 are skewed to the smaller end of the assemblage because only the smallest specimens, KNM-ER 1813 and 1805, preserve capacity and orbit size (from which body mass may be estimated), and because the associated postcranial remains, OH 62, are also from a small individual. However, the fragmentary remains affiliated with one another based on extrapolation from KNMER 1813’s anatomy display a range of size variation. OH 65 is the largest and about 15% larger than the next largest, OH 13. The body and brain size range of this group as suggested by these fragments should have a larger maximum size than exhibited by the more complete specimens and overlap substantially with the 1470 group (see details in Box 1). Postcrania: Evidence of relatively strong humeral to femoral cross-sectional properties in OH 62 have been used to argue for a substantial arboreal component to the locomotor repertoire of this group (134). Time based on East African remains: 2.09-1.44 million years ago H. habilis: Currently, only the type specimen is affiliated with this nomen. On the basis of dental anatomy, OH 7 can be excluded from H. erectus. However, taphonomic damage to the mandible renders its arcade shape unknown. As a result, the crushed and distorted OH 7 mandible cannot be definitively affiliated with either group of early Homo. Parsimony would suggest that its reconstruction will yield a match to one of the previously described early Homo groups and that the name, H. habilis, would then apply to either the 1470 group or the 1813 group. Size and Postcrania: OH 7 preserves two parietals from which a loose estimate of cranial capacity is 680 cc, which is consistent with any of the early Homo groups. The specimen also retains hand elements that cannot be presently compared with either group but which have been used to infer that the individual retained a significant amount of arboreal behavior in its locomotor repertoire. These inferences differ from those for H. erectus and are consistent with those made for the 1813 group (134), although they may also be consistent with the 1470 group, for which we lack positively affiliated postcranial remains. Time based on OH 7: 1.84 million years ago. Unaffiliated non-erectus early Homo: A number of specimens that can be assigned to Homo on the basis of various craniodental features, lack the specific arcade anatomy to be definitively assigned to one 4 or the other non-erectus Homo group. As noted above, these include some specimens that we consider likely to be affiliated with the 1813 group, such as KNM-ER 1802 and Uraha 501. These also include specimens for which we make no prediction due to missing anatomy, such as OH 16 (which has relatively narrow lower incisors but does not retain palatal or mandibular structures and has a relatively large canine root) and KNMER 1590 and 3732 – both of which have relatively large vaults (and in the case of 1590 also maxillary teeth), but which lack palatal or other facial anatomy to affiliate them definitively. It should be noted that the inferior face of KNM-ER 3732 may be plastically distorted. The exclusion of these three from both groups substantially influences our understanding of molar size in the groups as well as cranial capacity. Postcrania: A number of isolated postcranial limb elements cannot be affiliated with any certainty to either of the non-erectus Homo groups. In the past the large size of some of these has been used to argue for their inclusion with the large cranium KNM-ER 1470 – however, this seems unwarranted given the great size overlap present in the facial remains of both groups. Early H. erectus: Affiliations start from the type specimen for the species, Trinil 2, and work outward from this to other Asian and African specimens, including the Dmanisi remains. Substantial size variation exists within and across regions, with Dmanisi being the smallest population known to date. Given the time period of interest to this review, we have focused on the early African and Georgian remains, as detailed in the text and tables. Face: The face lacks the derived anatomy of the 1470 group being less tall and lacking the squared off anterior palate. The rounded anterior palate and large incisors are more similar to the 1813 group; however, H. erectus has a more derived, broader and parabolic arcade. Bigonial/bicondylar breadth, is not as great as in the 1470 group. The mandible is more gracile than in the 1813 group and has a narrow extramolar sulcus unlike the 1470 group. The ramus is probably not as tall as in the 1470 group. Dentition: Canines are more reduced than in Australopithecus or the 1813 group as are the premolars (but the premolars are not narrow as in the 1470 group), and unlike both groups of non-erectus Homo, H. erectus shows third molar occlusal area reduction. Molar cusp apex position is also placed closer to the outer margin of the tooth. Vault and Base: The vault is more angular in sagittal and posterior view than nonerectus Homo due in part to a series of variably expressed cranial superstructures (e.g., bregmatic and sagittal keeling, angular and occipital tori, and supraorbital tori). Some of these scale with overall cranial size (as proxied by endocranial volume). A continuous supraorbital torus and posttoral sulcus are present or incipient and a frontal trigone is often present. There is moderate postorbital constriction. Greatest breadth is low in the supramastoid region, and the posterior view is heptangular rather than rounded. The mandibular fossa is relatively less mediolaterally elongated, the cranial base is more flexed, and there is angulation between the petrous temporal and tympanic not currently known in early non-erectus Homo. Postcrania: Substantial portions of the postcranial skeleton are known for two African individuals with cranial affiliations to H. erectus, the subadult KNM-WT 15000 and the adult KNM-ER 1808. Both are relatively large individuals. Postcranial remains 5 of non-african H. erectus are known from Java, China and Georgia. These reveal regional variation is size and perhaps body proportions that follow general ecogeographic patterns. They also suggest a unique antero-posterior flattening and mediolateral broadening of the proximal femora, which may relate to use. Cross-sectional proportions suggest that H. erectus humeri are relatively less strong compared to their femora than is the case in the 1813 group (133), perhaps reflecting the loss of a substantial arboreal locomotor component to their behavior. Time based on East African remains: 1.89-0.90 million years ago 6 Table S1: Main fossil specimens attributed to earliest or early Homo by species group in this paper. Most isolated teeth, mandible fragments, postcranial fragments and specimens younger than 1.5 Ma are omitted. > 2.1 Ma Non-erectus Homo UR-501a A.L. 666-1 KNM-WT 42718 1470 Group Craniodental KNM-ER 1470 KNM-ER 1482 KNM-ER 1801 KNM-ER 60000 KNM-ER 62000 KNM-ER 62003 Postcranial None East Africa Equivocal KNM-BC 1 1813 Group East Africa H. habilis South Africa Equivocal Sts 19 Stw 151 2.1 to 1.5 Ma Unattributed Nonerectus Homo H. erectus South Africa Non-erectus Homo aff. H. erectus KNM-ER 1501 KNM-ER 1813 KNM-ER 1805 KNM-ER 3735 KNM-ER 42703b OH 13 OH 24 OH 62 OH 65 OH 7 KNM-ER 1590 KNM-ER 3732 KNM-ER 3891 KNM-ER 819 KNM-ER 1483 KNM-ER 1802 OH 16 KNM-ER 730 KNM-ER 820 KNM-ER 992 KNM-ER 1808 KNM-ER 3733 KNM-ER 3883 KNM-ER 42700 KNM-WT 15000 OH 9 b OH 12b Daka b KGA 10-1 b ?Stw-53c Stw-80 SK 27 SK-847 SK-15b SK-45 OH 62 KNM-ER 3735 OH 7 OH 8 KNM-ER 1472 KNM-ER 1481 KNM-ER 3228 KNM-WT 15000 KNM-ER 1808 None None a – may be younger than 2.0 Ma b – is or may be younger than 1.5 Ma c – may be older than 2.0 Ma 7 Table S2: Details of comparative brain, tooth, and body size of Australopithecus and Homo. These data are the basis for text Table 1. A. sediba (S. Africa) A. africanus (S. Africa) A. afarensisa (E. Africa) 1470 groupb (E. Africa) 1813 groupb (E. Africa) 420 (MH 1) 571 (Stw 505) 485 (Sts 5) 443 (MLD 37/38) 385 (Sts 60) 410 (Sts 71) 550 (444-2) 485 (333-45) 400 (162-28) 750 (1470) 510 (1813) 580 (1805) 595 (OH 24) 660 (OH 13) 420 454-461 (15.9) 478 (15.7) -- 6.9 (MH1) 8.7 (MLD 43) 6.5 (MLD 6+23) 8.4 (Sts 24) 8.16 (Sts 52) Mean (CV) -- 8.0 (12.5) 7.1 (198-17ab) 8.4 (200-1a) 8.1 (293-3) 8.6 (333x-20) 8.6 (333x-4) 9.7 (444-2) 8.4 (486-1) 8.4 (LH3) 8.4 (8.5) I1 labio-lingual, Wood # -- 6.9 (MLD 18) 5.9 (Sts 24) 6.6 (Sts 52b) -5.1 (MH1) 6.5 (8.1) 7.1 (MLD 11) 7.0 (MLD 23) 6.4 (Sts 24) 7.2 (Sts 52) 7.7 (LH2) 7.6 (333w-58) 7.3 (333w9a,b) 7.5 (4001a) 7.2 (444-2) 6.9 (582-1) 7.4 (4) 7.6 (486-1) 6.7 (198-17ab) 7.3 (200-1a) 8.1 (249-26) 8.2 (333x-2) 6.6 (417-1d) 7.6 (481-1) 7.8 (LH 3) Brain size cc (specimen #)c Mean (CV) Dental size (specimen #)d I1 labio-ling, Wood #186 248 Mean (CV) I2 labio-lingual, Wood #189 Unattributedb non-erectus Homo including H. habilis (E. Africa) 630 (OH 16) 680 (OH 7) 1470 group & 1813 group & unattributedb (E. Africa) Previous 3 columns combined H. aff. erectus (S. Africa) Early H. erectusb (E. Africa/ Dmanisi) - 586 (10.5) 655 (5.4) 629 (12.2) - 546 (D4500) 638 (D3444) 655 (D2282) 690 (42700) 727 (OH 12) 775 (D2280) 804 (3883) 848 (3733) 909 (WT 15000) 995 (Daka) 1067 (OH 9) -- 8 (OH 65) 8.2 (OH 16) 7.2 (OH 39) 7.7 (1590) Previous 3 columns combined 9.4 (15k) 8.2 (OH 29) 7.6 (D2700) -- -- 7.7 (6.5) 7.78 (5.6) 5.4 (60000) -- 6.6 (OH 7) 7.0 (OH 16) Previous 3 columns combined All = 8.4 (10.9) E. Africa = 8.8 (9.6) --- -6.1 (1813) 7.3 (OH 65) 6.8 (4.2) 7.0 (A.L. 666-1) 8.2 (808) 8.0 (OH16) 5.8 (OH 6) 6.3 (13.1) Previous 3 columns combined All = 787 (20.2) E. Africa = 863 (15.9) 6.0 (820) 6.9 (992) E. Africa = 6.45 (9.9) 8.5 (15k) 8.1 (OH 29) 6.9 (D2700) 8 7.8 (LH 6) Mean (CV) -- 6.9 (4.9) 7.5 (7.5) -- 6.7 (12.7) 7.2 (15.2) 7.1 (13.8) I2 labio-lingual, Wood -- 8.2 (MLD 18) 6.9 (Sts 24) 7.9 (Sts 52b) 6.7 (LH2) 8.2 (333w-58) 7.7 (4001a) 8.8 (444-2) 8.7 (437-2) 8.0 (MAK VP ½) 6.6 (60000) -- 7.4 (OH 7) 7.6 (OH 16) Previous 3 columns combined 7.0 (820) 7.0 (992) 8.3 (WT 15000) 7.4 (D2738) Mean (CV) -- 7.7 (8.6) 8.0 (9.6) -- -- 7.5 (1.9) 7.2 (7.3) 1548 (MH1) 1620 (MLD 6+) 1750 (Sts 1) 1690 (Sts 17) 1920 (Sts 21) 1760 (Sts 24) 2030 (Sts 28) Areas not provided as the published values are taken differently than those for other taxa 1850 (62000) 1560 (1813) 1770 (1805) 1790 (oh 24) 1640 (oh 13) 1675 (42703) 2010 (OH 16) 2090 (1590) Previous 3 columns combined All = 7.4 (8.2) E. Africa = 7.4 (10.1) 1560 (D2282) 1700 (D2700) 1490 (WT 15000) 1770 (807) -- 1795 (8.5) -- 1850 1687 (5.6) 2050 (2.8) 1798 (10.1) 1450 (MH1) 1310 (MH2) 1650 (MLD 18) 2070 (MLD 2) 1620 (MLD 40) 1470 (Sts 24) 1666 (Sts 52) 1950 (Sts 9) 1690 (Stw 1) Areas not provided as the published values are taken differently than those for other taxa 1460 (60000) 1755 (1482) 1835 (1801) 1500 (OH13) 1880 (OH 16) 1820 (OH 7) 1950 (1802) 1830 (1801) 1920 (UR 501) 1590 (1502) 1410 (OH 37) 1440 (3734) 1610 (1508) 1470 (1507) 1740 (1506A) 1590 (WT 42718) Previous 3 columns combined All = 1630 (7.8) E. Africa = 1630 (12.1) 1380 (7.2) 1731 (11.9) -- 1683 (11.7) -- 1630 (14.2) 1631 (13.2) 1767 (MH1) 2040 (MLD 6+) 2260 (MLD 9) 2180 (Sts 12) 1960 (Sts 17) 2170 (Sts 22) 2700 (Sts 28) Areas not provided as the published values are taken differently than those for other taxa 2016 (62000) 2020 (OH16) 2570 (1590) [1940] (A.L. 666-1) Previous 3 columns combined -- 2218 (11.7) -- -- 1640 (1813) 1730 (1805) 1890(OH24) 1810(OH13) 1833 (42703) 1880 (OH 65) 1797 (5.3) 2177 (15.8) 1933 (13.1) Areas not provided as the published values are taken differently 1790 (60000) 2100 (1482) 1680(OH13) 1840 (1805) 2460 (OH16) 2110 (OH7) Previous 3 columns #251 1 M area, Wood #213 Mean (CV) M1 area, Wood #289 Mean (CV) 2 M area, Wood #225 Mean (CV) M2 area, Wood #317 1858 (MH1) 1720 (MH2) All = 7.83 (10.6) E. Africa = 8.3 (3.4) 1560 (D211) 1500 (D2738) 1390 (WT 15000) 1370 (992) 1330 (820) 1450 (730) 1780 (806) 1610 (OH 22) 1810 (OH 51) All = 1533 (11.3) E. Africa = 1534 (13) 1560 (D2282) 1860 (3733) 1500 (WT 15000) 1560 (1808) 1630 (D2700) All = 1622 (8.7) E. Africa = 1640 (11.8) 1420 (D211) 1510(WT 15000) 9 than those for other taxa Mean (CV) 1789 (5.5) 2390 (1802) 2730 (UR 501) 2000 (OH 37) 1650 (3734) 2130 (2597) 1900 (1506) 1790 (1507) combined 1380 (D2738) 1630 (992) 1510 (730) 1990 (806) All = 1573 (14.1) E. Africa = 1660 (13.7) 1945 (11.3) 1760 (6.4) 2128 (16.2) 2043 (15.8) Previous 3 columns combined Previous 3 columns combined -- Body Mass orbit estimates -- 27/29 (Sts 71) 28/22 (Sts 5) -- 46/51 (1470) 35/31 (1813) 30/36 (OH 24) -- 95% CI Range Kappelman/Aiello -- 18-38/26-36 (Sts 71) 19-40/19-27 (Sts 5) -- 34-70/43-63 24-50/ 22-31(1813) 21-43/ 29-42 (OH 24) -- predicted value by specimen in kg from Kappelman/Aiello (specimen #) Mean of Predicted values Kappelman/Aiello RMA Body Size Body Mass kg /Femur length (specimen #)e (1470) -- 57/58 (3883) 59/65 (3733) 59/-- (WT 15000) 40-58/48-72 (3883) 41–85/54-82 (3733) -- --/25 -- -- 33/34 -- 37/36 -- 36 (MH 2) 32 (MH 1) 45/434 (Stw 99) 41 (Stw 443) 41 (Stw 311) 38 (Sts 34) 38 (Stw 389) 34 (Stw 25) 33 (Stw 392) 33 (TM 1513) 30 (Stw 102) 30/276 (Sts 13, 34) 28 (Stw 347) 23 (Stw 358) 34 (19)/-- 50/382 (333-3) 48 (333x-26) 46/375 (827-1) 45 (KSD-VP-1/1) 43 (333-7) 41 (333-4) 40 (333-w-56) 34 (333-8) 28/281 (288-1) 27 (129a) -- --/315 (OH 62) 64 (3228) 50/401 (1472) 57/396 (1481) 32 (OH 35) 31 (OH 8) Previous 3 columns combined 57 (SK-1896) 53-58(SK 2045) [30](SKX 10924) Mean of 33 (9)/-40 (20)/ --44 (31)/ 44 (32)/ [43](32) body mass (CV)/ 346 (16) 398 (1) 371 (13) femur length (CV) a A. afarensis specimen numbers are Afar Locality (A.L.) numbers unless otherwise indicated. b Numbers without a prefix are KNM-ER numbers. WT numbers are KNM-WT. OH are Olduvai Hominid. D are Dmanisi. c Endocranial capacity for: A. sediba (4); A. africanus (121); A. afarensis (122); and individually for Homo following primarily (38) as well as (6, 29, 44, 49). d Dental measurement definitions indicated by (41) and these and most data from (38); A. afarensis from (132); A. sediba as above; Newer Homo data not in (41) follow (3, 29, 133). e Body mass estimates follow data sources in (8, 21, 58). Femur length CVs are raw values not corrected for dimensionality. 41.5-86/-- (15k) 58/86 68 (736) 63/485 (1808) 54/456 (OH 28) 51/429 (WT 15000) 51/432 (OH 34) 49 (Dmanisi large) 41 (Dmanisi small) 40 (Gona) All = 52 (20)/450 (9) E. Africa = 55 (19)/ 450 (9) 10 References and Notes 1. T. E. Cerling, Development of grasslands and savannas in East Africa during the Neogene. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 97, 241–247 (1992). doi:10.1016/0031-0182(92)90211-M 2. T. E. Cerling, J. G. Wynn, S. A. Andanje, M. I. Bird, D. K. Korir, N. E. Levin, W. Mace, A. N. Macharia, J. Quade, C. H. Remien, Woody cover and hominin environments in the past 6 million years. Nature 476, 51–56 (2011). Medline doi:10.1038/nature10306 3. L. C. Aiello, S. C. Antón, Human biology and the origins of Homo: An introduction to Supplement 6. Curr. Anthropol. 53 (suppl. 6), S269–S277 (2012). doi:10.1086/667693 4. R. Potts, Environmental and behavioral evidence pertaining to the evolution of early Homo. Curr. Anthropol. 53 (suppl. 6), S299–S317 (2012). doi:10.1086/667704 5. M. G. Leakey, F. Spoor, M. C. Dean, C. S. Feibel, S. C. Antón, C. Kiarie, L. N. Leakey, New fossils from Koobi Fora in northern Kenya confirm taxonomic diversity in early Homo. Nature 488, 201–204 (2012). Medline doi:10.1038/nature11322 6. L. R. Berger, D. J. de Ruiter, S. E. Churchill, P. Schmid, K. J. Carlson, P. H. Dirks, J. M. Kibii, Australopithecus sediba: A new species of Homo-like australopith from South Africa. Science 328, 195–204 (2010). Medline doi:10.1126/science.1184944 7. R. Pickering, P. H. G. M. Dirks, Z. Jinnah, D. J. de Ruiter, S. E. Churchil, A. I. Herries, J. D. Woodhead, J. C. Hellstrom, L. R. Berger, Australopithecus sediba at 1.977 Ma and implications for the origins of the genus Homo. Science 333, 1421–1423 (2011). Medline doi:10.1126/science.1203697 8. D. Lordkipanidze, M. S. Ponce de León, A. Margvelashvili, Y. Rak, G. P. Rightmire, A. Vekua, C. P. Zollikofer, A complete skull from Dmanisi, Georgia, and the evolutionary biology of early Homo. Science 342, 326–331 (2013). Medline doi:10.1126/science.1238484 9. D. J. de Ruiter, T. J. DeWitt, K. B. Carlson, J. K. Brophy, L. Schroeder, R. R. Ackermann, S. E. Churchill, L. R. Berger, Mandibular remains support taxonomic validity of Australopithecus sediba. Science 340, 1232997 (2013). 10.1126/science.1232997 Medline doi:10.1126/science.1232997 10. S. C. Antón, Early Homo: Who, when, and where. Curr. Anthropol. 53 (suppl. 6), S278–S298 (2012). doi:10.1086/667695 11. P. N. Gathogo, F. H. Brown, Revised stratigraphy of Area 123, Koobi Fora, Kenya, and new age estimates of its fossil mammals, including hominins. J. Hum. Evol. 51, 471–479 (2006). Medline doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2006.05.005 12. C. S. Feibel, C. J. Lepre, R. L. Quinn, Stratigraphy, correlation, and age estimates for fossils from Area 123, Koobi Fora. J. Hum. Evol. 57, 112–122 (2009). Medline doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2009.05.007 13. P. Schmid, S. E. Churchill, S. Nalla, E. Weissen, K. J. Carlson, D. J. de Ruiter, L. R. Berger, Mosaic morphology in the thorax of Australopithecus sediba. Science 340, 1234598 (2013). 10.1126/science.1234598 Medline doi:10.1126/science.1234598 14. E. Mayr, On the concepts and terminology of vertical subspecies and species. Natl. Res. Counc. Comm. Common Probl. Genet. Paleontol. Syst. Bull. 2, 11–16 (1944). 15. L. S. B. Leakey, P. V. Tobias, J. R. Napier, A new species of the genus Homo from Olduvai Gorge. Nature 202, 7–9 (1964). Medline doi:10.1038/202007a0 16. V. Alexeev, The Origin of the Human Race (Progress, Moscow, 1986). 17. B. Wood, ‘Homo rudolfensis’ Alexeev, 1986-fact or phantom? J. Hum. Evol. 36, 115–118 (1999). Medline doi:10.1006/jhev.1998.0246 18. B. Wood, M. Collard, The human genus. Science 284, 65–71 (1999). Medline doi:10.1126/science.284.5411.65 19. B. Wood, J. Baker, Evolution in the genus Homo. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 42, 47– 69 (2011). 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-102209-144653 doi:10.1146/annurevecolsys-102209-144653 20. B. Wood, Human evolution: Fifty years after Homo habilis. Nature 508, 31–33 (2014). Medline doi:10.1038/508031a 21. T. E. Cerling, F. K. Manthi, E. N. Mbua, L. N. Leakey, M. G. Leakey, R. E. Leakey, F. H. Brown, F. E. Grine, J. A. Hart, P. Kaleme, H. Roche, K. T. Uno, B. A. Wood, Stable isotope-based diet reconstructions of Turkana Basin hominins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 10501–10506 (2013). Medline doi:10.1073/pnas.1222568110 22. M. Sponheimer, Z. Alemseged, T. E. Cerling, F. E. Grine, W. H. Kimbel, M. G. Leakey, J. A. Lee-Thorp, F. K. Manthi, K. E. Reed, B. A. Wood, J. G. Wynn, Isotopic evidence of early hominin diets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 10513–10518 (2013). doi:10.1073/pnas.1222579110 23. Y. Haile-Selassie, B. M. Latimer, M. Alene, A. L. Deino, L. Gibert, S. M. Melillo, B. Z. Saylor, G. R. Scott, C. O. Lovejoy, An early Australopithecus afarensis postcranium from Woranso-Mille, Ethiopia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 12121–12126 (2010). Medline doi:10.1073/pnas.1004527107 24. H. Pontzer, Ecological energetics in early Homo. Curr. Anthropol. 53 (suppl. 6), S346–S358 (2012). doi:10.1086/667402 25. C. V. Ward, W. H. Kimbel, D. C. Johanson, Complete fourth metatarsal and arches in the foot of Australopithecus afarensis. Science 331, 750–753 (2011). Medline doi:10.1126/science.1201463 26. C. V. Ward, W. H. Kimbel, E. H. Harmon, D. C. Johanson, New postcranial fossils of Australopithecus afarensis from Hadar, Ethiopia (1990-2007). J. Hum. Evol. 63, 1–51 (2012). Medline doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.11.012 27. A. Hill, S. Ward, A. Deino, G. Curtis, R. Drake, Earliest Homo. Nature 355, 719–722 (1992). Medline doi:10.1038/355719a0 28. G. Suwa, T. D. White, F. C. Howell, Mandibular postcanine dentition from the Shungura Formation, Ethiopia: Crown morphology, taxonomic allocations, and Plio-Pleistocene hominid evolution. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 101, 247–282 (1996). Medline doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199610)101:2<247::AIDAJPA9>3.0.CO;2-Z 29. W. H. Kimbel, in The First Humans: Origin and Early Evolution of the Genus Homo, F. E. Grine, J. G. Fleagle, R. E. Leakey, Eds. (Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology Series, Springer, Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2009), pp. 31–38. 30. G. P. Rightmire, D. Lordkipanidze, in The First Humans: Origin and Early Evolution of the Genus Homo, F. E. Grine, J. G. Fleagle, R. E. Leakey, Eds. (Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology Series, Springer, Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2009), pp. 39–48. 31. B. Wood, in The First Humans: Origin and Early Evolution of the Genus Homo, F. E. Grine, J. G. Fleagle, R. E. Leakey, Eds. (Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology Series, Springer, Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2009), pp. 17–28. 32. F. Spoor, M. G. Leakey, P. N. Gathogo, F. H. Brown, S. C. Antón, I. McDougall, C. Kiarie, F. K. Manthi, L. N. Leakey, Implications of new early Homo fossils from Ileret, east of Lake Turkana, Kenya. Nature 448, 688–691 (2007). Medline doi:10.1038/nature05986 33. W. H. Kimbel, R. C. Walter, D. C. Johanson, K. E. Reed, J. L. Aronson, Z. Assefa, C. W. Marean, G. G. Eck, R. Bobe, E. Hovers, Y. Rak, C. Vondra, T. Yemane, D. York, Y. Chen, N. M. Evensen, P. E. Smith, Late Pliocene Homo and Oldowan tools from the Hadar Formation (Kada Hadar Member), Ethiopia. J. Hum. Evol. 31, 549–561 (1996). doi:10.1006/jhev.1996.0079 34. T. G. Bromage, F. Schrenk, F. W. Zonneveld, Paleoanthropology of the Malawi Rift: An early hominid mandible from the Chiwondo Beds, northern Malawi. J. Hum. Evol. 28, 71–108 (1995). doi:10.1006/jhev.1995.1007 35. D. Curnoe, A review of early Homo in southern Africa focusing on cranial, mandibular and dental remains, with the description of a new species (Homo gautengensis sp. nov.). Homo 61, 151–177 (2010). Medline doi:10.1016/j.jchb.2010.04.002 36. M. C. Dean, B. A. Wood, Basicranial anatomy of Plio-Pleistocene hominids from East and South Africa. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 59, 157–174 (1982). Medline doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330590206 37. W. H. Kimbel, D. C. Johanson, Y. Rak, Systematic assessment of a maxilla of Homo from Hadar, Ethiopia. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 103, 235–262 (1997). Medline doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(199706)103:2<235::AID-AJPA8>3.0.CO;2-S 38. J. Moggi-Cecchi, P. V. Tobias, A. D. Beynon, The mixed dentition and associated skull fragments of a juvenile fossil hominid from Sterkfontein, South Africa. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 106, 425–465 (1998). Medline doi:10.1002/(SICI)10968644(199808)106:4<425::AID-AJPA2>3.0.CO;2-I 39. F. E. Grine, H. F. Smith, C. P. Heesy, E. J. Smith, in The First Humans: Origin and Early Evolution of the Genus Homo, F. E. Grine, J. G. Fleagle, R. E. Leakey, Eds. (Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology Series, Springer, Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2009), pp. 49–62. 40. C. B. Stringer, in Topics in Primate and Human Evolution, B. A. Wood, L. B. Martin, P. Andrews, Eds. (Alan R. Liss, New York, 1986), pp. 266–294. 41. B. A. Wood, Koobi Fora Research Project Volume 4, Hominid Cranial Remains (Clarendon, Oxford, 1991). 42. G. P. Rightmire, The Evolution of Homo erectus (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 1990). 43. P. Shipman, A. Walker, The costs of becoming a predator. J. Hum. Evol. 18, 373–392 (1989). doi:10.1016/0047-2484(89)90037-7 44. R. Potts, A. K. Behrensmeyer, A. Deino, P. Ditchfield, J. Clark, Small midPleistocene hominin associated with East African Acheulean technology. Science 305, 75–78 (2004). Medline doi:10.1126/science.1097661 45. S. W. Simpson, J. Quade, N. E. Levin, R. Butler, G. Dupont-Nivet, M. Everett, S. Semaw, A female Homo erectus pelvis from Gona, Ethiopia. Science 322, 1089– 1092 (2008). Medline doi:10.1126/science.1163592 46. R. R. Graves, A. C. Lupo, R. C. McCarthy, D. J. Wescott, D. L. Cunningham, Just how strapping was KNM-WT 15000? J. Hum. Evol. 59, 542–554 (2010). Medline doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2010.06.007 47. B. Asfaw, W. H. Gilbert, Y. Beyene, W. K. Hart, P. R. Renne, G. WoldeGabriel, E. S. Vrba, T. D. White, Remains of Homo erectus from Bouri, Middle Awash, Ethiopia. Nature 416, 317–320 (2002). Medline doi:10.1038/416317a 48. C. S. Feibel, F. H. Brown, I. McDougall, Stratigraphic context of fossil hominids from the Omo group deposits: Northern Turkana Basin, Kenya and Ethiopia. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 78, 595–622 (1989). Medline doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330780412 49. R. Broom, J. T. Robinson, A new type of fossil man. Nature 164, 322–323 (1949). Medline doi:10.1038/164322a0 50. J. T. Robinson, The australopithecines and their bearing on the origin of man and of stone tool-making. S. Afr. J. Sci. 57, 3–13 (1961). 51. F. E. Grine, in Humanity from African Naissance to Coming Millennia - Colloquia in Human Biology and Palaeoanthropology, P. V. Tobias, M. A. Raath, J. MoggiCecchi, G. A. Doyle, Eds. (Florence Univ. Press, Florence, Italy, 2001), pp. 107– 115. 52. L. Gabunia, A. Vekua, D. Lordkipanidze, C. C. Swisher 3rd, R. Ferring, A. Justus, M. Nioradze, M. Tvalchrelidze, S. C. Antón, G. Bosinski, O. Jöris, M. A. Lumley, G. Majsuradze, A. Mouskhelishvili, Earliest Pleistocene hominid cranial remains from Dmanisi, Republic of Georgia: Taxonomy, geological setting, and age. Science 288, 1019–1025 (2000). Medline doi:10.1126/science.288.5468.1019 53. C. C. Swisher 3rd, G. H. Curtis, T. Jacob, A. G. Getty, A. Suprijo, Widiasmoro, Age of the earliest known hominids in Java, Indonesia. Science 263, 1118–1121 (1994). Medline doi:10.1126/science.8108729 54. R. Larick, R. L. Ciochon, Y. Zaim, Sudijono, Y. Suminto, F. Rizal, M. Aziz, M. Reagan, M. Heizler, Early Pleistocene 40Ar/39Ar ages for Bapang Formation hominins, Central Jawa, Indonesia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 4866–4871 (2001). Medline doi:10.1073/pnas.081077298 55. R. X. Zhu, R. Potts, Y. X. Pan, H. T. Yao, L. Q. Lü, X. Zhao, X. Gao, L. W. Chen, F. Gao, C. L. Deng, Early evidence of the genus Homo in East Asia. J. Hum. Evol. 55, 1075–1085 (2008). Medline doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.08.005 56. D. Lordkipanidze, T. Jashashvili, A. Vekua, M. S. Ponce de León, C. P. E. Zollikofer, G. P. Rightmire, H. Pontzer, R. Ferring, O. Oms, M. Tappen, M. Bukhsianidze, J. Agusti, R. Kahlke, G. Kiladze, B. Martinez-Navarro, A. Mouskhelishvili, M. Nioradze, L. Rook, Postcranial evidence from early Homo from Dmanisi, Georgia. Nature 449, 305–310 (2007). Medline doi:10.1038/nature06134 57. S. C. Antón, Natural history of Homo erectus. Yearb. Phys. Anthropol. 46 (suppl. 37), 126–170 (2003). Medline doi:10.1002/ajpa.10399 58. K. L. Baab, The taxonomic implications of cranial shape variation in Homo erectus. J. Hum. Evol. 54, 827–847 (2008). Medline doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.11.003 59. F. Spoor, Palaeoanthropology: Small-brained and big-mouthed. Nature 502, 452–453 (2013). Medline doi:10.1038/502452a 60. T. Holliday, Body size, body shape, and the circumscription of the genus Homo. Curr. Anthropol. 53 (suppl. 6), S330–S345 (2012). doi:10.1086/667360 61. S. C. Antón, J. J. Snodgrass, Origins and evolution of genus Homo: New perspectives. Curr. Anthropol. 53 (suppl. 6), S479–S496 (2012). doi:10.1086/667692 62. J. M. Plavcan, Body size, size variation, and sexual size dimorphism in early Homo. Curr. Anthropol. 53 (suppl. 6), S409–S423 (2012). doi:10.1086/667605 63. E. S. Vrba, “On the connections between paleoclimate and evolution,” in Paleoclimate and Evolution with Emphasis on Human Origins, E. S. Vrba, G. H. Denton, T. C. Partridge, L. H. Burckle, Eds. (Yale Univ. Press, New Haven, CT, 1995), pp. 24–45. 64. P. B. deMenocal, Plio-Pleistocene African climate. Science 270, 53–59 (1995). Medline doi:10.1126/science.270.5233.53 65. J. G. Wynn, Influence of Plio-Pleistocene aridification on human evolution: Evidence from paleosols of the Turkana Basin, Kenya. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 123, 106– 118 (2004). Medline doi:10.1002/ajpa.10317 66. K. E. Reed, Early hominid evolution and ecological change through the African PlioPleistocene. J. Hum. Evol. 32, 289–322 (1997). Medline doi:10.1006/jhev.1996.0106 67. R. Potts, Hominin evolution in settings of strong environmental variability. Quat. Sci. Rev. 73, 1–13 (2013). doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2013.04.003 68. M. H. Trauth, M. A. Maslin, A. L. Deino, M. R. Strecker, A. G. Bergner, M. Dühnforth, High- and low-latitude forcing of Plio-Pleistocene East African climate and human evolution. J. Hum. Evol. 53, 475–486 (2007). Medline doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2006.12.009 69. P. B. deMenocal, African climate change and faunal evolution during the PliocenePleistocene. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 220, 3–24 (2004). doi:10.1016/S0012821X(04)00003-2 70. R. Bobe, A. K. Beherensmeyer, The expansion of grassland ecosystems in Africa in relation to mammalian evolution and origin of the genus Homo. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 207, 399–420 (2004). doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2003.09.033 71. R. Potts, Evolution and climate variability. Science 273, 922–923 (1996). doi:10.1126/science.273.5277.922 72. P. B. deMenocal, Climate and human evolution. Science 331, 540–542 (2011). Medline doi:10.1126/science.1190683 73. J. D. Kingston, Shifting adaptive landscapes: Progress and challenges in reconstructing early hominid environments. Yearb. Phys. Anthropol. 134 (suppl. 45), 20–58 (2007). Medline doi:10.1002/ajpa.20733 74. N. E. Levin, Compilation of East Africa soil carbonate stable isotope data, Integrated Earth Data Applications 10.1594/IEDA/100231 (2013). 75. N. E. Levin, F. H. Brown, A. K. Behrensmeyer, R. Bobe, T. E. Cerling, Paleosol carbonates from the Omo Group: Isotopic records of local and regional environmental change in East Africa. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 307, 75–89 (2011). doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2011.04.026 76. A. L. Deino, J. D. Kingston, J. M. Glen, R. K. Edgar, A. Hill, Precessional forcing of lacustrine sedimentation in the late Cenozoic Chemeron Basin, Central Kenya Rift. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 247, 41–60 (2006). doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2006.04.009 77. M. H. Trauth, M. A. Maslin, A. L. Deino, A. Junginger, M. Lesoloyia, E. O. Odada, D. O. Olago, L. A. Olaka, M. R. Strecker, R. Tiedemann, Human evolution in a variable environment: The amplifier lakes of Eastern Africa. Quat. Sci. Rev. 29, 2981–2988 (2010). doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.07.007 78. M. Grove, Speciation, diversity, and Mode 1 technologies: The impact of variability selection. J. Hum. Evol. 61, 306–319 (2011). Medline doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.04.005 79. M. H. Trauth, M. A. Maslin, A. Deino, M. R. Strecker, Late Cenozoic moisture history of East Africa. Science 309, 2051–2053 (2005). Medline doi:10.1126/science.1112964 80. M. A. Maslin, B. Christensen, Tectonics, orbital forcing, global climate change, and human evolution in Africa: Introduction to the African paleoclimate special volume. J. Hum. Evol. 53, 443–464 (2007). Medline doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.06.005 81. C. S. Feibel, Debating the environmental factors in hominid evolution. GSA Today 7 (no. 3), 1–7 (1997). Medline 82. C. S. Feibel, J. M. Harris, F. H. Brown, in Koobi Fora Research Project, Vol. 3: The Fossil Ungulates: Geology, Fossil Artiodactyls, and Palaeoenvironments, J. M. Harris, Ed. (Clarendon, Oxford, 1991), pp. 321–370. 83. G. M. Ashley, Orbital rhythms, monsoons, and playa lake response, Olduvai Basin, equatorial East Africa (ca. 1.85–1.74 Ma). Geology 35, 1091–1094 (2007). doi:10.1130/G24163A.1 84. C. J. Lepre, R. L. Quinn, J. C. A. Joordens, C. C. Swisher 3rd, C. S. Feibel, PlioPleistocene facies environments from the KBS Member, Koobi Fora Formation: Implications for climate controls on the development of lake-margin hominin habitats in the northeast Turkana Basin (northwest Kenya). J. Hum. Evol. 53, 504–514 (2007). Medline doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.01.015 85. A. L. Deino, (40)Ar/(39)Ar dating of Bed I, Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, and the chronology of early Pleistocene climate change. J. Hum. Evol. 63, 251–273 (2012). Medline doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2012.05.004 86. P. S. Ungar, Dental evidence for the reconstruction of diet in African early Homo. Curr. Anthropol. 53 (suppl. 6), S318–S329 (2012). doi:10.1086/666700 87. M. Domínguez-Rodrigo, T. R. Pickering, S. Semaw, M. J. Rogers, Cutmarked bones from Pliocene archaeological sites at Gona, Afar, Ethiopia: Implications for the function of the world’s oldest stone tools. J. Hum. Evol. 48, 109–121 (2005). Medline doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.09.004 88. S. P. McPherron, Z. Alemseged, C. W. Marean, J. G. Wynn, D. Reed, D. Geraads, R. Bobe, H. A. Béarat, Evidence for stone-tool-assisted consumption of animal tissues before 3.39 million years ago at Dikika, Ethiopia. Nature 466, 857–860 (2010). Medline doi:10.1038/nature09248 89. M. T. Domínguez-Rodrigo, R. Barba, C. P. Egeland, Deconstructing Olduvai: A Taphonomic Study of the Bed I Sites (Springer, Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2007). 90. J. V. Ferraro, T. W. Plummer, B. L. Pobiner, J. S. Oliver, L. C. Bishop, D. R. Braun, P. W. Ditchfield, J. W. Seaman 3rd, K. M. Binetti, J. W. Seaman Jr., F. Hertel, R. Potts, Earliest archaeological evidence of persistent hominin carnivory. PLOS ONE 8, e62174 (2013). Medline doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062174 91. D. R. Braun, J. W. Harris, N. E. Levin, J. T. McCoy, A. I. Herries, M. K. Bamford, L. C. Bishop, B. G. Richmond, M. Kibunjia, Early hominin diet included diverse terrestrial and aquatic animals 1.95 Ma in East Turkana, Kenya. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 10002–10007 (2010). Medline doi:10.1073/pnas.1002181107 92. C. Lemorini, T. W. Plummer, D. R. Braun, A. N. Crittenden, P. W. Ditchfield, L. C. Bishop, F. Hertel, J. S. Oliver, F. W. Marlowe, M. J. Schoeninger, R. Potts, Old stones’ song: Use-wear experiments and analysis of the Oldowan quartz and quartzite assemblage from Kanjera South (Kenya). J. Hum. Evol. 72, 10–25 (2014). Medline doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2014.03.002 93. D. R. Braun, T. Plummer, P. Ditchfield, J. V. Ferraro, D. Maina, L. C. Bishop, R. Potts, Oldowan behavior and raw material transport: Perspectives from the Kanjera Formation. J. Archaeol. Sci. 35, 2329–2345 (2008). doi:10.1016/j.jas.2008.03.004 94. C. J. Lepre, H. Roche, D. V. Kent, S. Harmand, R. L. Quinn, J. P. Brugal, P. J. Texier, A. Lenoble, C. S. Feibel, An earlier origin for the Acheulian. Nature 477, 82–85 (2011). Medline doi:10.1038/nature10372 95. C. W. Kuzawa, J. M. Bragg, Plasticity and human life history strategy: Implications for contemporary human variation and the evolution of genus Homo. Curr. Anthropol. 53 (suppl. 6), S369–S382 (2012). doi:10.1086/667410 96. A. B. Migliano, M. Guillon, The effects of mortality, subsistence, and ecology on human adult height and implications for Homo evolution. Curr. Anthropol. 53 (suppl. 6), S359–S368 (2012). doi:10.1086/667694 97. C. Dean, M. G. Leakey, D. Reid, F. Schrenk, G. T. Schwartz, C. Stringer, A. Walker, Growth processes in teeth distinguish modern humans from Homo erectus and earlier hominins. Nature 414, 628–631 (2001). Medline doi:10.1038/414628a 98. M. C. Dean, B. H. Smith, in The First Humans: Origin and Early Evolution of the Genus Homo, F. E. Grine, J. G. Fleagle, R. E. Leakey, Eds. (Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology Series, Springer, Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2009), pp. 101–120. 99. T. R. Turner, F. Anapol, C. J. Jolly, Growth, development, and sexual dimorphism in vervet monkeys (Cercopithecus aethiops) at four sites in Kenya. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 103, 19–35 (1997). Medline doi:10.1002/(SICI)10968644(199705)103:1<19::AID-AJPA3>3.0.CO;2-8 100. S. M. Lehman, Ecological and phylogenetic correlates to body size in the Indriidae. Int. J. Primatol. 28, 183–210 (2007). doi:10.1007/s10764-006-9114-4 101. A. D. Gordon, S. E. Johnson, E. E. Louis Jr., Females are the ecological sex: Sexspecific body mass ecogeography in wild Sifaka populations (Propithecus spp.). Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 151, 77–87 (2013). Medline doi:10.1002/ajpa.22259 102. S. C. Antón, W. R. Leonard, M. L. Robertson, An ecomorphological model of the initial hominid dispersal from Africa. J. Hum. Evol. 43, 773–785 (2002). Medline doi:10.1006/jhev.2002.0602 103. H. Pontzer, J. M. Kamilar, Great ranging associated with greater reproductive investment in mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 192–196 (2009). Medline doi:10.1073/pnas.0806105106 104. L. C. Aiello, P. Wheeler, The expensive tissue hypothesis: The brain and digestive system in human and primate evolution. Curr. Anthropol. 36, 199–221 (1995). doi:10.1086/204350 105. K. Isler, C. P. van Schaik, How our ancestors broke through the gray ceiling: Comparative evidence for cooperative breeding in early Homo. Curr. Anthropol. 53 (suppl. 6), S453–S465 (2012). doi:10.1086/667623 106. K. Isler, C. P. van Schaik, Allomaternal care, life history and brain size evolution in mammals. J. Hum. Evol. 63, 52–63 (2012). Medline doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2012.03.009 107. K. Isler, C. P. van Schaik, The expensive Brain: A framework for explaining evolutionary changes in brain size. J. Hum. Evol. 57, 392–400 (2009). Medline doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2009.04.009 108. W. R. Leonard, M. L. Robertson, J. J. Snodgrass, C. W. Kuzawa, Metabolic correlates of hominid brain evolution. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 136, 5–15 (2003). Medline doi:10.1016/S1095-6433(03)00132-6 109. A. Navarrete, C. P. van Schaik, K. Isler, Energetics and the evolution of human brain size. Nature 480, 91–93 (2011). Medline doi:10.1038/nature10629 110. J. J. Snodgrass, W. R. Leonard, M. L. Robertson, in Evolution of Hominid Diets: Integrating Approaches to the Study of Palaeolithic Subsistence, J.-J. Hublin, M. Richards, Eds. (Springer, Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2009), pp. 15–29. 111. J. E. Smith, E. M. Swanson, E. Reed, K. E. Holekamp, Evolution of cooperation among mammalian carnivores and its relevance to hominin evolution. Curr. Anthropol. 53 (suppl. 6), S436–S452 (2012). doi:10.1086/667653 112. J. C. K. Wells, The capital economy in hominin evolution: How adipose tissue and social relationships confer phenotypic flexibility and resilience in stochastic environments. Curr. Anthropol. 53 (suppl. 6), S466–S478 (2012). doi:10.1086/667606 113. K. Laland, J. Odling-Smee, L. Feldman, Cultural niche construction and human evolution. J. Evol. Biol. 14, 22–33 (2001). doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.2001.00262.x 114. F. J. Odling-Smee, K. Laland, M. Feldman, Niche Construction: The Neglected Process in Evolution (Monographs in Population Biology No. 37, Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton, NJ, 2003). 115. R. Ferring, O. Oms, J. Agustí, F. Berna, M. Nioradze, T. Shelia, M. Tappen, A. Vekua, D. Zhvania, D. Lordkipanidze, Earliest human occupations at Dmanisi (Georgian Caucasus) dated to 1.85-1.78 Ma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 10432–10436 (2011). Medline doi:10.1073/pnas.1106638108 116. S. C. Antón, C. C. Swisher III, Early dispersals of Homo from Africa. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 33, 271–296 (2004). doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.33.070203.144024 117. L. C. Aiello, Five years of Homo floresiensis. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 142, 167–179 (2010). Medline 118. K. L. Baab, K. P. McNulty, Size, shape, and asymmetry in fossil hominins: The status of the LB1 cranium based on 3D morphometric analyses. J. Hum. Evol. 57, 608–622 (2009). Medline doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.08.011 119. K. L. Baab, K. P. McNulty, K. Harvati, Homo floresiensis contextualized: A geometric morphometric comparative analysis of fossil and pathological human samples. PLOS ONE 8, e69119 (2013). Medline doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0069119 120. D. Kubo, R. T. Kono, Y. Kaifu, Brain size of Homo floresiensis and its evolutionary implications. Proc. Biol. Sci. 280, 20130338 (2013). Medline doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.0338 121. H. J. M. Meijer, L. W. van den Hoek Ostende, G. D. van den Bergh, J. de Vos, The fellowship of the hobbit: The fauna surrounding Homo floresiensis. J. Biogeogr. 37, 995–1006 (2010). doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2010.02308.x 122. R. L. Holloway Jr., Culture: A human domain. Curr. Anthropol. 10 (suppl. 4), 395– 412 (1969). doi:10.1086/201036 123. G. Isaac, The diet of early man: Aspects of archaeological evidence from Lower and Middle Pleistocene Sites in Africa. World Archaeol. 2, 278–299 (1971). Medline doi:10.1080/00438243.1971.9979481 124. G. Isaac, The food-sharing behavior of protohuman hominids. Sci. Am. 238, 90–108 (1978). Medline doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0478-90 125. A. Walker, R. Leakey, Eds., The Nariokotome Homo erectus Skeleton (Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, MA, 1993). 126. R. Levins, Evolution in Changing Environments (Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton, NJ, 1968). 127. S. Neubauer, P. Gunz, G. W. Weber, J.-J. Hublin, Endocranial volume of Australopithecus africanus: New CT-based estimates and the effects of missing data and small sample size. J. Hum. Evol. 62, 498–510 (2012). Medline doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2012.01.005 128. R. L. Holloway, M. S. Yuan, in The Skull of Australopithecus afarensis, W. H. Kimbel, Y. Rak, D. C. Johanson, Eds. (Oxford Univ. Press, New York, 2004), pp. 123–135. 129. W. H. Kimbel, Y. Rak, D. C. Johanson, Eds., The Skull of Australopithecus afarensis (Oxford Univ. Press, New York, 2004). 130. G. P. Rightmire, D. Lordkipanidze, A. Vekua, Anatomical descriptions, comparative studies and evolutionary significance of the hominin skulls from Dmanisi, Republic of Georgia. J. Hum. Evol. 50, 115–141 (2006). Medline doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2005.07.009 131. J. Kappelman, The evolution of body mass and relative brain size in fossil hominids. J. Hum. Evol. 30, 243–276 (1996). doi:10.1006/jhev.1996.0021 132. L. C. Aiello, B. A. Wood, Cranial variables as predictors of hominine body mass. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 95, 409–426 (1994). Medline doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330950405 133. C. Ruff, Femoral/humeral strength in early African Homo erectus. J. Hum. Evol. 54, 383–390 (2008). Medline doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.09.001 134. C. Ruff, Relative limb strength and locomotion in Homo habilis. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 138, 90–100 (2009). Medline doi:10.1002/ajpa.20907 135. G. T. Schwartz, Growth, development, and life history throughout the evolution of Homo. Curr. Anthropol. 53 (suppl. 6), S395–S408 (2012). doi:10.1086/667591 136. S. Semaw, M. J. Rogers, J. Quade, P. R. Renne, R. F. Butler, M. DominguezRodrigo, D. Stout, W. S. Hart, T. Pickering, S. W. Simpson, 2.6-Million-year-old stone tools and associated bones from OGS-6 and OGS-7, Gona, Afar, Ethiopia. J. Hum. Evol. 45, 169–177 (2003). Medline doi:10.1016/S0047-2484(03)00093-9 137. H. Pontzer, D. A. Raichlen, R. W. Shumaker, C. Ocobock, S. A. Wich, Metabolic adaptation for low energy throughput in orangutans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 14048–14052 (2010). Medline doi:10.1073/pnas.1001031107 138. J. J. Snodgrass, in Human Biology: An Evolutionary and Biocultural Approach, S. Stinson, B. Bogin, D. O’Rourke, Eds. (Wiley, New York, ed. 2, 2012), pp. 327– 386. 139. K. K. Schroepfer, B. Hare, H. Pontzer, Energy expenditure in semi free-ranging chimpanzees measured using doubly labeled water. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. S54, 263 (2012). 140. A. Hrdlička, The Neanderthal phase of man. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. 57, 249–274 (1927). 141. C. L. Brace, The Stages of Human Evolution (Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1967). 142. M. H. Wolpoff, Competitive exclusion among Lower Pleistocene hominids: The single species hypothesis. Man (Lond) 6, 601–614 (1971). doi:10.2307/2799185 143. Y. Kimura, L. L. Jacobs, T. E. Cerling, K. T. Uno, K. M. Ferguson, L. J. Flynn, R. Patnaik, Fossil mice and rats show isotopic evidence of niche partitioning and change in dental ecomorphology related to dietary shift in Late Miocene of Pakistan. PLOS ONE 8, e69308 (2013). Medline doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0069308 144. V. M. Oelze, J. S. Head, M. M. Robbins, M. Richards, C. Boesch, Niche differentiation and dietary seasonality among sympatric gorillas and chimpanzees in Loango National Park (Gabon) revealed by stable isotope analysis. J. Hum. Evol. 66, 95–106 (2014). Medline doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2013.10.003 145. H. A. Thomassen, A. H. Freedman, D. M. Brown, W. Buermann, D. K. Jacobs, Regional differences in seasonal timing of rainfall discriminate between genetically distinct East African giraffe taxa. PLOS ONE 8, e77191 (2013). Medline doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0077191 146. C. Groves, P. Grubb, Ungulate Taxonomy (Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, Baltimore, 2011). 147. R. S. Seymour, thesis, University of Kent at Canterbury, UK (2001). 148. D. M. Brown, R. A. Brenneman, K. P. Koepfli, J. P. Pollinger, B. Milá, N. J. Georgiadis, E. E. Louis Jr., G. F. Grether, D. K. Jacobs, R. K. Wayne, Extensive population genetic structure in the giraffe. BMC Biol. 5, 57 (2007). Medline doi:10.1186/1741-7007-5-57 149. I. J. Gordon, A. W. Illius, Resource partitioning by ungulates on the Isle of Rhum. Oecologia 79, 383–389 (1989). Medline doi:10.1007/BF00384318 150. S. W. Wang, D. W. Macdonald, Feeding habits and niche partitioning in a predator guild composed of tigers, leopards and dholes in a temperate ecosystem in central Bhutan. J. Zool. 277, 275–283 (2009). doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2008.00537.x 151. J. C. A. Joordens, H. B. Vonhof, C. S. Feibel, L. J. Lourens, G. Dupont-Nivet, J. H. J. L. van der Lubbe, M. J. Sier, G. R. Davies, D. Kroon, An astronomically-tuned climate framework for hominins in the Turkana basin. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 307, 1–8 (2011). doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2011.05.005 152. T. W. Plummer, P. W. Ditchfield, L. C. Bishop, J. D. Kingston, J. V. Ferraro, D. R. Braun, F. Hertel, R. Potts, Oldest evidence of tool making hominins in a grassland-dominated ecosystem. PLOS ONE 4, e7199 (2009). Medline doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007199