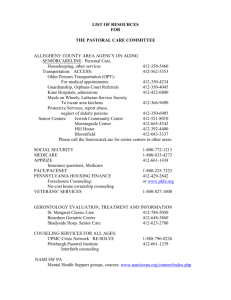

allegheny county health black and white - UCSUR

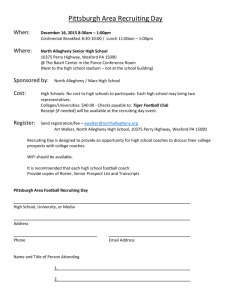

advertisement