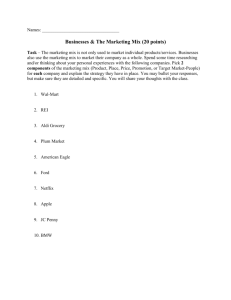

The Impact of Big Box Grocers on Southern California

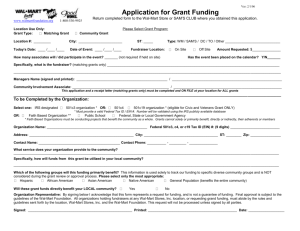

advertisement