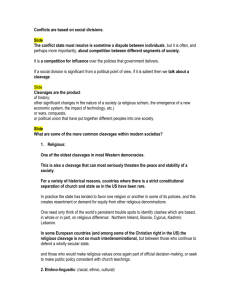

The Impact of Cross-Cutting Cleavages on Citizens' Political

advertisement