Conflicts are based on social divisions

advertisement

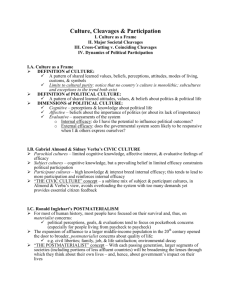

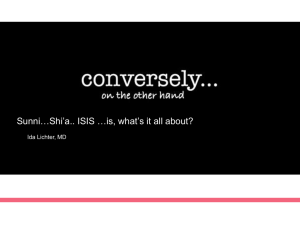

Conflicts are based on social divisions. Slide The conflict state must resolve is sometime a dispute between individuals, but it is often, and perhaps more importantly, about competition between different segments of society. It is a competition for influence over the policies that government delivers. If a social division is significant from a political point of view, if it is salient then we talk about a cleavage. Slide Cleavages are the product of history; other significant changes in the nature of a society (a religious schism, the emergence of a new economic system, the impact of technology, etc.) or wars, conquests, or political union that have put together different peoples into one society. Slide What are some of the more common cleavages within modern societies? 1. Religious: One of the oldest cleavages in most Western democracies. This is also a cleavage that can most seriously threaten the peace and stability of a society. For a variety of historical reasons, countries where there is a strict constitutional separation of church and state as in the US have been rare. In practice the state has tended to favor one religion or another in some of its policies, and this creates resentment or demand for equity from other religious denominations One need only think of the world’s persistent trouble spots to identify clashes which are based, in whole or in part, on religious difference: Northern Ireland, Bosnia, Cyprus, Kashmir, Lebanon. In some European countries (and among some of the Christian right in the US) the religious cleavage is not so much interdenominational, but between those who continue to defend a wholly secular state, and those who would make religious values once again part of official decision-making, or seek to make public policy consistent with church teachings. 2. Etnhno-lingusitic: (racial, ethnic, cultural) There are many societies in which race has been (Uganda) and or remains a significant cleavage (the US, South Africa, Malaysia). Most of these cleavages are the legacy of colonialism and imperialism. In many other cases, political union and conquests or dynastic marriages have joined different ethnic and linguistic communities (which are not so distinct racially) in one society. English and French in Canada; Flemish and Walloon in Belgium; or French, German and Italian in Switzerland are advanced democracies with a significant ethno-lingusitic cleavage. Also; Spain, France, and Britain. It is important to understand that these cleavages are never just about language, but also about cultural differences rooted in or sustained through linguistic difference 3. Center-periphery Virtually all societies –city-states or micro-states excepted – will have a center, and what makes it the center is not its location but the centrality within the society. London, Washington DC, New York, Paris, Rome Sometimes: it is the largest city or most populous region, It may be the political capital, and or the most economically developed and productive region. In most cases, then, this centrality will be a source of resentment to regions or areas that feel disadvantaged or excluded by not being at the center. 4. Urban-rural: In many parts of the world today more that 80% of the population lives in cities. This doesn’t mean that there isn’t a contrast and often a conflict of interest between those who live in the cities and those who still live in the country. Indeed, rural Americans tend to be more socially conservatives that their urban counterparts, and thus appeal by politicians and parties to “family values” tend to resonate more strongly in rural areas. Similarly, opposition to gun control is strongest in rural America. 5. Class: All countries have economic classes. Any society will have a cleavage structure that will reflect some, but probably not all five cleavages. Political parties or interest groups will succeed or fail to obtain policies that respond to the needs of the segments of society they represent. In this way cleavages are accommodated within the polity, or not. When a cleavage is most fully accommodated by responsive policies of the government the division represented by the cleavage ceases to be a basis for political mobilization. But a cleavage that cannot be accommodated leads to civil war (Yugoslavia) or partition (see the former Czechoslovakia) or other forms of extreme conflict. Slide The crucial distinction here is between reinforcing and cross-cutting cleavages. Reinforcing cleavages: one or more bases of identity (or difference) are shared by the same population. This means, in effect, that on virtually every issue, the lines of opposition will separate the same groups from each other. Examples: Northern Ireland: Catholics (underclass) South Africa, Rodhesia (Zimbabwe) In Belgium, the Flemish (Dutch) population is largely Catholic and generally more affluent that the Walloons (francophone), who are more secular. Generally speaking, we would expect reinforcing cleavages to lead to conflict. The situation is easier where cleavages do not overlap so neatly. Consider a situation where there is a strong religious cleavage, and at the same time a strong class cleavage among those who are on either side of the religious divide. Here the cleavages offset each other perfectly: those who are united by religion are divided by economic class, and vice versa. What do you think is better for a democratic society? Reinforcing or cross-cutting cleavages. On different issues the majority and minority groups will not be identical. The more crosscutting cleavages there are, the more political majorities will be shifting temporary, favoring or alienating no particular group on a regular basis. In this way, cross-cutting cleavages can be stabilizing in a pluralistic society. A central task for the political system is to contain or defuse the differences and contests of interest that emerge out of these various identities. This is perhaps the element of politics that is identified as the resolution of conflict, the engineering of consent, or the art of compromise. If one side of any division is always the “winner” in battles over policy, then the losing part will soon feel exploited and alienated. The long-term consequences of such an outcome are not good for a political community. Slide The modern history of Iraq (and the British): Iraq was assembled according to mostly British (and some French) strategic calculations rather that with the idea of creating a state that is likely to last. France and Britain were in control of large portions of former Ottoman territory in the Middle East. The carving started in January 1916 when the French and the British met to divide up the future spoils of war. The resulting Sykes-Picot Agreement provided for French control over Greater Lebanon and Syria, while Britain was to retain control over the former Ottoman provinces of Basra and Baghdad. Territory of the new Iraqi State The incorporation of Mosul. The precise territorial configuration of the new state had yet to be determined. There was no dispute that the provinces of Baghdad and Basra were components in the fledgling Iraqi state. However, the northernmost of the three former Ottoman provinces – Mosul – raised a number of important strategic concerns (large oil reserves). The Treaty of Sevres: concluded in August 1920 between the victorious allies and the defeated Ottoman rules Empire – had envisaged a Separate Kurdish state (Turkish + Iraqi Kurds). The League of Nations granted the area to the United Kingdom as a mandate. A successful nationalist movement in Turkey (Kamal Ataturk) swept away the remnants of the Ottoman rule in Turkey and reestablished Turkish control over Kurdish areas in the southeastern part of Turkey. Ataturk then claimed Mosul as Turkish territory and backed up his claim by an invasion of the province. The British stopped the Turkish advances and drove the Turks back across what will later become the border between Turkey and Iraq. In 1925 the League of Nations formally recognized this border. The British decided to unite the three Ottoman provinces of Baghdad, Mosul, and Basra into one nation-state called Iraq (a name borrowed from the medieval past of the region) despite the significant religious, linguistic, ethnic, and tribal divisions running through Iraqi society. Access to oil was almost certainly the primary motivating factor behind the British decision to incorporate Mosul into the new state of Iraq (will have tragic consequences later because of incorporation of ethnic Kurds) Consequences: The sectarian (religious) divide: The former Ottoman province of Basra was (and still is) populated predominantly by Shi’a Muslims; Baghdad and Mosul, by Sunnis. Under the Ottoman rule, the three provinces of Mosul, Baghdad, and Basra were administered by Sunni Arabs, a tradition that the British intentionally did not disturb. Since the days of the Ottoman Empire, military and political power has been concentrated almost exclusively in the hands of the Sunni Arab minority. Tensions between Sunni and Shi’a were seldom driven by purely sectarian differences. Certainly, the secular Sunni regime viewed the political role played by prominent religious leaders in the south with some concern, but the major problem was the congruence of sectarian divisions with division of wealth and political power. Sunni control over political and economic power effectively relegated the majority of Shi’a to a position of permanent subordination. Sunni control over the levers of power and the distribution of the spoils of office has had predictable consequences – a resentment of the Shi’a that periodically erupts into open and violent rebellion. Favoring Sunni minority at the expense of the more numerous Shi’a Favoring Sunni Arabs over others Sunni Arabs have controlled the levers of economic and political power throughout the history of modern Iraq. Sunni dominant was manifest not only in the form of the Hashemite dynasty but throughout the political elite. Dominance was even more pronounced at the local level. A similar pattern prevailed in the armed forces. Traditional center-periphery cleavage is reinforced by religious and ethnic divisions. Fractures along ethnic lines: The central and southern parts of Iraq are ethnically Arab, while the north-eastern portion of the country is populated by Kurds and smaller populations of Turkomen and Assyrians. Arabs 80% Kurds 15-20% The formal incorporation of Mosul into the Iraqi state in 1925 was intended, in part, at least to help reduce the numerical dominance of the Shi’a. The Kurds never accepted central rule (one of the constants in modern political history) This resistance has often manifested itself in violent uprisings.