1 The FLN's Strategy for Gaining an Independent Algeria, 1954

advertisement

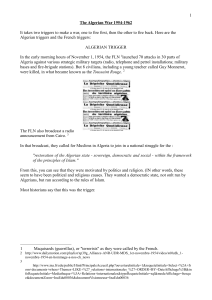

The FLN’s Strategy for Gaining an Independent Algeria, 1954-1962 Mallory Davis University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Ronald E. McNair Program, Summer 2007 Mentor: Dr. Bruce Fetter, Department of History Introduction The Front de Libération Nationale (FLN) of Algeria was formed to obtain complete independence from French colonialism. It became the ruling political party after the Algerian Revolution (1954-1962). This organization was originally composed of both military and political leaders. Members also included Algerian nationalists, recruited Algerians, Algerians living in France, and Europeans sympathetic to the nationalist cause. Under the leadership of the FLN, Algerians waged an eight-year war against their occupiers. This research will analyze the history of this movement during the Algerian Revolution. I will focus on its goals for independence and the strategies used in both the military and political arenas to obtain them. Lastly, I will assess whether or not these goals changed at all throughout the revolution and if the struggle was successful in creating the independent Algeria the FLN hoped for. Methodologies For my research I am analyzing both primary and secondary sources pertaining to the FLN at the time of the revolution. My resources are limited to translations from French and Arabic documents and English language originals. My primary sources, which were written at the time of the war, consist of the Internet database of United States foreign relations documents (FRUS) and two edited volumes. The first of these latter is Ahmed Ben Bella, a biographical work of one of the FLN’s founders and the first president of independent Algeria. The second book, A Dying Colonialism by Frantz Fanon, a psychiatrist from Martinique (West Indies), was written in 1959 while he was aiding the FLN as a physician. I utilized FRUS to determine the political tactics used by the FLN to the US for independence and support. All the documents contained in FRUS were at one time very private or only directed for a specific audience. Until they were made available to the public online, many were scattered around the country in libraries and this information was not available elsewhere. My secondary sources provided me with general background information, which familiarized me with the origins of the war. Historians who analyzed primary sources wrote these works after the war. These sources also analyze military and political tactics used by both sides. Literature Review Ahmed Ben Bella was compiled by Robert Merle and consists of a series of interviews with Ben Bella from just after the war. Ben Bella’s own words describe his hopes for Algeria and his personal reasons for wanting to start a revolution. His details of how the FLN formed and firsthand accounts of conflicts between its leaders are very useful to understand the internal political workings of the organization. He focuses on his duties and contributions to the revolution as well as his opinions on negotiations that took place 1 between France and Algeria. As the leader of independent Algeria’s first government, Ben Bella is a good source to gauge the intentions of the FLN. Frantz Fanon’s book A Dying Colonialism was written in 1959, a time in the war when there was no end in sight. Fanon’s focus was to highlight the importance of the common Algerian to the war effort. He describes the role of sons and fathers who take up arms or produce propaganda in favor of the FLN.11 He explains how an entire family could be recruited to hide or care for FLN members. He also spends a portion of his book explaining the role of women in the FLN; they assisted by participating in guerilla attacks and formed their own cells.2 His accounts were useful when I was researching the strategies used by the military. The US foreign relations database available on the Internet has archived personal memos as well as public documents. These documents reveal the attitudes of the US toward the FLN’s appeals for recognition. The US was caught between staying loyal to the French and believing in independence for the Algerians. Alistair Horne’s A Savage War of Peace is a key secondary source. It details the war from month to month, delving into every important military operation and political strategy on both sides of the war. I read this book first; I needed to familiarize myself with both the French and the Algerian side of the war. I also utilized it to learn about French Algeria before the war to understand the strategies the FLN used throughout the war. Martha Crenshaw Hutchinson’s Revolutionary Terrorism examines the use of terrorism as a military tactic. Hutchinson sees the FLN as an example of revolutionaries who used terrorism as a means to win independence. Hutchinson argues that the FLN did not have a strategic alternative to terrorism.3 She outlines how terrorism was used to gain support from Algerians, as well as against the French.4 She concludes that terrorism helped “to keep the revolution politically alive.”5 This book was beneficial to my understanding of the FLN’s formation during a time when there were various other competing organizations. The FLN in Algeria: Party Development in a Revolutionary Society by Henry F. Jackson focuses on the specific goals and the strategies used to achieve them. Jackson outlines the original decree of the FLN dating from November of 1954. He also details the Soummam Valley Congress of 1956, which was an important meeting of the leaders directing the war from inside Algeria.6 Jackson’s research focused on the FLN as primarily a political party and follows it in the years after the revolution. This book provided me with FLN political strategy and conflict. Lastly, Matthew Connelly wrote two important works on the FLN’s international political strategies. According to his article, “Rethinking the Cold War and Decolonization: The Grand Strategy of the Algerian War for Independence,” the FLN’s main goal in terms of the West was to take advantage of the threat of the East (communism) supporting a nation seeking independence. Connelly also found that the 1 Frantz Fanon, A Dying Colonialism (New York: Grove Press, Inc., 1965), 102-105. Ibid., 108. 3 Martha Crenshaw Hutchinson, Revolutionary Terrorism, (Stanford: Hoover Institution Press, 1978), 23. 4 Ibid., 40, 61. 5 Ibid., 152. 6 Henry F. Jackson, The FLN in Algeria: Party Development in a Revolutionary Society, (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1977), 32- 43. 2 2 FLN used anti-colonialism to rally support of smaller countries.7 Throughout his article and book, A Diplomatic Revolution: Algeria’s Fight for Independence and the Origin of the Post-Cold War Era, Connelly tracks important international meetings and negotiations. Brief History of French Algeria Until 1830, Algeria had been a part of the Ottoman Empire.8 Upon the French conquest, Algeria was not incorporated as a typical colony. France envisioned Algeria as an integral part of the republic; it was referred to as Algérie française (French Algeria). European settlers in Algeria, called pieds noirs, were not limited to Frenchmen.9 At the time of the revolution, these settlers came from such places as Italy, Spain, and Greece as well.10 French became the language of both the settlers and the Algerians.11 Many Algerians traveled to metropolitan France for work opportunities, this group of workers would play a role later in the revolution.12 At the time of the revolution the population of Algeria reached an estimated ten million, the pieds noirs made up one million of this number. The Algerians, though much larger in number, became a minority in their own country. Colons (wealthy settlers) and Algerians sympathetic to France controlled local politics. Algerians were disproportionately represented nationally as well; the Europeans received the same amount of seats as Algerians in the National Assembly.13 In the years leading up to the revolution, most Algerians had experienced near famine conditions. They were living in either rural, infertile areas, as the Europeans claimed the productive land, or in urban slums. With improved medical conditions there came a dramatic population increase, which only compounded poor conditions.14 They felt the French had treated them unfairly and demanded justice. Strong nationalist sentiments had already been brewing among the politically aware, however, a 1945 protest in the northern town of Sétif turned into a massacre when the French murdered 50,000 Algerians (a number estimated by Algerian nationalists).15 Formation of the FLN After the First World War, Algerian nationalists began to form their own political organizations as France lessened restrictions on their formation.16 These groups could often be bitter rivals because of differing ideologies such as the importance of violence or the inclusion of religious reformation. Just before the revolution, there were three main organizations, all of which were being closely watched by the French government. The first was the Mouvement pour le Triomphe des Libertés Démocratiques (MTLD) led by 7 Matthew Connelly, “Rethinking the Cold War and Decolonization: The Grand Strategy of the Algerian War for Independence,” International Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 33, 2 (May, 2001): 223. 8 Alistair Horne, A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954-1962. (Middlesex: Penguin Books, 1977), 28. 9 Ibid., 30. 10 Ibid., 47. 11 Jackson, xiv. 12 Hutchinson, 3. 13 Horne, 33-34. 14 Ibid, 62-64. 15 15 Jackson,15. 16 Ibid.,10. 3 Massali Hadj, who formed the MTLD upon his return from exile for founding two other nationalist political organizations. The MTLD had a secret branch called the Organisation Spéciale (OS), which was disbanded by the French in 1950. Next was the Ulama founded by Sheikh Ben Badis, a religious leader. Lastly was the Union Démocratique du Manifeste Algérien (UDMA), led by Ferhat Abbas. Though differences existed, at the center of all these organizations was the hope of an end to colonialism and an independent Algeria. Because of this, the groups tried to pool their resources and become united.17 Dissenters within the original MTLD and the OS can be attributed as the predecessors of the FLN.The original leaders were divided into those operating from the interior of the country and those working from the exterior in such places as Cairo and Tunis. The original leaders were: Hocine Aït Ahmed, Ahmed Bella, Mostefa Ben Boulaid, Larbi Ben M’hidi, Rabah Bitat, Mohamed Didouche, Mohamed Khider, Ali Mahsas, Omar Ourmrane, Lakhdar Ben Tobbal, and Belkacem Krim.18 Those leading from the exterior included Ben Bella, Aït Ahmed, and Khider. Several of the leaders, such as Ben Bella, Ourmrane, and Krim, received their training from the French military during the Second World War. Within the FLN, there were smaller organizations specifically for the military and politics. The Armée de Libération Nationale (ALN) was the military branch of the FLN. The Comité Révolution d’Unité ed d’Action (CRUA) was created for political purposes. It made the final decisions when it came to the revolution. It consisted of thirty-four members and gave more power to those working in the interior. In 1958 a provisional government, the Gouvernement Provisoire de la République Algérienne (GPRA) was set up to gain recognition from other countries with the goal of illegitimating the current French government. Its headquarters were in Tunis and originally led by Ferhat Abbas.19 The original ideology of the FLN assumed that unity among Algerians was necessary to win the war. The FLN eliminated all other competing organizations and individuals who did not join in the struggle.20 A second tenet of FLN ideology was that violence was necessary.21 There were also underlying tones of an Algerian identity as well as Islamic unity.22 Ahmed Ben Bella suggested that the FLN had no central ideology, which was beneficial in wartime because no one was excluded from joining. Once the war ended, however, there was trouble uniting the country under the new government.23 Martha Crenshaw Hutchinson agrees with this stating: “The FLN did not possess a highly structured or comprehensive ideology; the revolution was simply guided by nationalism”.24 FLN Military The military had several specific goals. The first was to isolate the French army and European settlers and to destroy the administration. The purpose of this goal was to 17 Hutchinson, 3-6. Horne, 75-77. 19 Hutchinson, 7-9. 20 Jackson, 24. 21 Hutchinson, 23. 22 Jackson, 24-25. 23 Robert Merle, Ahmed Ben Bella, (New York: Walker and Company, 1965), 123. 24 Hutchinson, 12 18 4 deter colonialism. Guerilla warfare and terrorism were used to realize these goals. Targets included both pieds noirs and French military personnel.25 The country was separated into five military zones, called wilayas, which were led by colonels of the ALN.26 Soldiers of the ALN were first placed in rural areas.27 Many men were trained outside of Algeria on military bases provided by Tunisia.28 The first attacks of the war took place on November 1, 1954, All Saints Day, where roughly ten French soldiers and two pieds noirs were murdered by members of the FLN. The deaths were a result of dozens of simultaneous bombings and other guerilla tactics throughout the country’s military bases. At this point in the war, the FLN purposely avoided killing European civilians; the first two lost were supposedly accidental.29 Attacks on military personnel were important for acquiring weapons, which were necessary to the FLN. Those leading the FLN from the exterior, primarily Ahmed Ben Bella, were concerned with arming the ALN. Ben Bella accounts how he acquired arms from Tunisia and Egypt and smuggled them into the country. The first arms had come from Libya.30 Arms also came from the Soviet Union and Spain via other Arab countries.31 This type of support concerned the French, who tried to enlist the help of the US to stop these shipments. Ironically, a large portion of the FLN arms was seized from the French.32 Terrorist cells were usually centered in the cities, such as the capital, Algiers, or other metropolitan areas such as Oran or Constantine, which were all along the Mediterranean Coast. The Battle of Algiers, which took place from 1956-1957, was a turning point in the way Algerian terrorists operated. Saadi Yacef was the FLN leader of the city of Algiers and at his orders European civilians became targets.33 Frantz Fanon discusses the use of women in these terrorist cells in his book A Dying Colonialism. The French heavily policed these large cities and women passed through the checkpoints much more easily. It was not uncommon for a woman to leave her family to join the FLN. She would go to the mountains for training and be welcomed back by a proud father. Women of the FLN were very strong and becoming independent, because they believed in nationalism.34 The targets of women bombers were usually civilians, however they did assist in the assassinations French officials. The most common method of bombing by women was to place a bag carrying a timed bomb in a crowded public area. Locations 25 Hutchinson, 61-62. Ibid., 9. 27 Ibid., 12. 28 United States Department of State, John P. Glennon, Editor. Foreign relations of the United States, 19581960. Arab-Israeli dispute; United Arab Republic; North Africa Volume XIII, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1958-1960, http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1711.dl/FRUS.FRUS1958-60v13, 15 July 2007, 820. 29 Horne, 90-93. 30 Merle. 93. 31 United States Department of State, Glenn W. LaFantasie, Editor, Foreign relations of the United States, 1958-1960. Western Europe Volume VII, Part II Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 26 1958-1960, http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1711.dl/FRUS.FRUS1958-60v07p2. 15 July 2007, 756; FRUS, 1958-1960, Vol XIII, 814. 32 FRUS, 1958-60, Vol XIII, 869. 33 Horne, 183-184. 34 Fanon, 107-109. 5 known as popular places for pieds noirs were attacked.35 The second major goal of the military was to gain the support of the Algerian population, which included eliminating any dissenters.36 Terrorism was used as a form of intimidation to gain new recruits and show the power of the FLN. Names of “informers” that had been killed could be found in pamphlets distributed by the FLN. To build loyalty among the people of Algeria, the FLN proved they were actively seeking independence from France. Algerians living in France could also be subject to terrorism, their money and support were important to the war effort in Algeria.37 In response to French counterterrorism, which eventually became torture, the FLN grew in number.38 The French government considered FLN members “captured insurgents” and did not refrain from implementing the death penalty.39 Propaganda was successful in swaying popular opinion, which led to more recruits. As mentioned before, European civilians eventually became targets. The FLN refused to agree to a cease-fire agreement without proof that their independence would follow, as a result, both sides were forced to gain or send more troops and adopt more extreme strategies.40 FLN Politics As outlined by Matthew Connelly, the FLN’s political goals were as follows: “1. Internationalization the Algerian question. 2. Realization of North African unity in its natural Arab-Muslim framework. 3. In the framework of the United Nations charter, affirmation of our sympathy with regard to all nations that support our liberating actions”.41 During the war, the main concern with the politicians of the FLN was to make the problem public. It was not until after the war that Algeria could become an Arab nation like those nearby. Hocine Aït Ahmed was responsible for internationalizing the war from New York City while Mohammed Khider worked from Cairo.42 Propaganda, attendance at international meetings, and direct correspondence with French, as well as US, Arab, and communist governments were all means of internationalizing their problem. Politics within the FLN were often complicated. There were tensions between the leaders of the interior and those of the exterior, and differing viewpoints were commonplace. The leaders of the interior, under extremist Ramdane Abane, held a conference in the Soummam Valley in Algeria and did not include Ben Bella and those of the exterior. This conference created a legislative board, the Conseil National de la Révolution Algérienne (CRNA), which was responsible for making all military and political decisions, and an executive board, the Comité de Coordination et d’exécution (CCE), which was in charge of all the FLN’s other organizations. Every leader on these boards came from the interior of the country.43 Then, just a few months after the 35 Hutchinson, 23. Merle, 94.37 37 Hutchinson, 63. 38 Ibid., 128. 39 Ibid., 106. 40 Jackson, 26. 41 Matthew Connelly, A Diplomatic Revolution: Algeria’s Fight for Independence and the Origin of the Post- Cold War Era (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 74. 42 Ibid, 74. 43 Jackson, 34. 36 6 conference, the French arrested five members of the exterior (including Ben Bella) in Morocco. This worked to the advantage of the FLN as it made political decisions less complex.44 Propaganda was an international and local tool used to familiarize others with the nationalist cause. The FLN began broadcasting over the radio in 1956 in a program called, Voice of Algeria. This program kept Algerians informed of the military’s progress and involved in the revolution.45 Films and newspapers designed to vilify the French were distributed abroad.46 Throughout the war the subject matter of FLN propaganda shifted from military to political, showing that the FLN felt political recognition was more important than proving military strength.47 According to FRUS, the US promised France on several occasions that the government would not support Algerian politicians working in the country, but there was not much they could do to stop any of their activity.48 In the case of the US the FLN used the threat of communism to their advantage. They sought recognition from China and the Soviet Union as fervently as they did from the US. Being aligned with France against communism, the US would have no choice but to join the war if its presence became too strong in Algeria.49 Pleas for recognition of the problem were proved successful when the issue was mentioned by Saudi Arabia to the UN Security Council in December of 1954.50 In 1960 the GPRA was recognized by the Soviet Union.51 During the intense battle of Algiers (1956-57), the FLN organized a general strike to take place in the eight days of the UN assembly. The aim of this strike was to draw favorable attention, not to commit any violent acts. The French army broke the strike within several days, yet, the tactics used were extreme and gave the army a bad reputation.52 Most important to the politicians of the FLN were the final negotiations with France that began in 1960 and were finalized in 1962. They were able to receive their original goal of independence.53 President Charles de Gaulle had tried to appease his country, and especially the pieds noirs by holding on to Algeria as part of the French republic, finally that was no longer and option.54 Near the end of the delegations, the FLN saw the importance of internal organization. The leaders wanted to make sure that once independence was gained, there would not be any policy conflicts between members of the new government. This meeting was conducted in Tripoli and only moderately successful. A lack of strong political ideology during the war left Algerians with a weak government in the end.55 44 Ibid., 47-48. Fanon, 82-85. 46 A Diplomatic, 135, 137. 47 Ibid., 136. 48 FRUS, 1958-1960, Vol XIII, 658. 49 Rethinking, 221. 50 Ibid., 224. 51 Ibid., 221. 52 Horne, 190-191. 53 Hutchinson, 17. 54 Horne, 463. 55 Jackson, 57, 63. 45 7 Conclusion The original goal declared by the FLN in 1954 was reached after eight years. The Algerians made it clear that they would settle for nothing less than complete independence from France. Their military strategies changed throughout the war as the organization grew along with the opposition. Political organizations created by the Soummam conference also changed the ALN’s structure. Though the FLN sought political attention internationally, the final agreements took place solely between the French and the Algerians, as the French had wanted. These international tactics did however place pressure on the French to come to a resolution. For continuing research it will be imperative to learn French and Arabic in order to analyze the wealth of un-translated sources. The Algerian struggle also raises questions of the international scene at the same time. Just before the revolution, France had been defeated at Dien Bien Phu, which shocked many countries. Perhaps the Algerians saw this as a sign of weakness in France and decided their chances of winning a revolution were favorable at that time. Also, during the struggle both Tunisia and Morocco gained their independence from France. Did this give Algerians hope for their independence? Could Algeria have won without the support of these newly independent nations? Lastly, what impact did the revolution have on the rest of the Arab world? BIBLIOGRAPHY Primary Sources Fanon, Frantz. A Dying Colonialism. New York: Grove Press, Inc., 1965. Merle, Robert. Ahmed Ben Bella. New York: Walker and Company, 1965. United States Department of State. Glennon, John P., Editor. Foreign relations of the United States, 1958-1960. Arab-Israeli dispute; United Arab Republic; North Africa Volume XIII. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. 1958-1960. http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1711.dl/FRUS.FRUS195860v13. 15 July 2007. United States Department of State. LaFantasie, Glenn W., Editor. Foreign relations of the United States, 1958-1960. Western Europe Volume VII, Part II. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. 1958-1960. http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1711.dl/FRUS.FRUS1958-60v07p2. 15 July 2007. Secondary Sources Connelly, Matthew. A Diplomatic Revolution: Algeria’s Fight for Independence and the Origin of the Post- Cold War Era. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002. Connelly, Matthew. “Rethinking the Cold War and Decolonization: The Grand Strategy of the Algerian War for Independence.” International Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 33, 2 (May, 2001): 221-245. Horne, Alistair. A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954-1962. Middlesex: Penguin Books, 1977. Hutchinson, Martha Crenshaw. Revolutionary Terrorism. Stanford: Hoover Institution Press, 1978. Jackson, Henry F. The FLN in Algeria: Party Development in a Revolutionary Society. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1977. 8