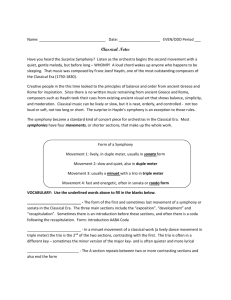

Haydn symph2 - Naur, Peter

advertisement