Fetal Pig Dissection Manual

advertisement

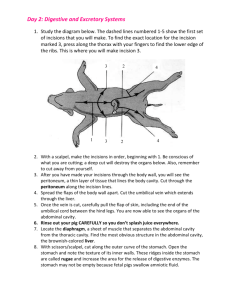

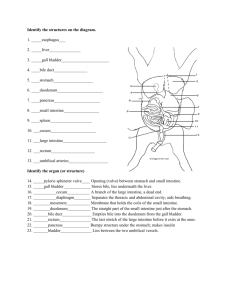

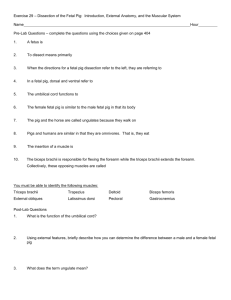

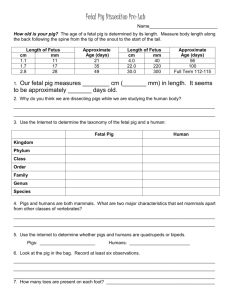

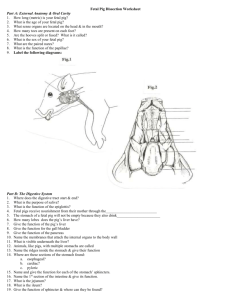

Anatomy and Physiology Fetal Pig Dissection Guide Revised 2010 Objectives: To study the gross internal structure of a representative mammal whose anatomy closely resembles a human. As you proceed through the following exercises, you should ask yourself if the internal anatomy of the pig is identical to or different from your own body. As a second leading theme, pay particular attention to the relationships among organs and groups of organs. Structural parts are not “just there”, in random locations. Their specific layout within the body contributes to making certain functions possible. Therefore, for every structure seen, determine to what organ system it belongs; how it is related to different organ systems; what general function the organ or structure serves; and how its shape, form, and specific position contribute to its general function. Also, pay attention to whether or not there is perfect symmetry in the internal arrangement of organs. Basic Directions: The word, dissect means to “expose to view”. Therefore, never cut more than is absolutely necessary to expose a part. Where cutting cannot be avoided, make sure you have fully identified and studied the structural connections of a part before you cut it. Ask your instructor before cutting anything if you are unsure of the potential damage it may cause to structures yet to be studied. Familiarize yourself with your basic tools of scissors, scalpel and probe. The scissors will give you more control than a scalpel. The blunt probe can be used as an extension of your finger. Take care to clean your tools by dipping them in the disinfectant solution and drying them prior to placing back in their case. Always wear protective goggles and gloves while working. Wear available aprons and lab coats, as desired. Clean your lab table area with disinfectant solution and a sponge at the end of the lab period. Study what you experience in the lab by using lecture notes and packets, your text, study guides and websites you find on the Internet. See the lecture notes and suggested Internet links on the instructor’s webpage. In Summary: 1. Read the directions carefully before you begin to dissect and obey them word for word, unless directed otherwise by your instructor. 2. Identify structures to be cut before cutting them. 3. Cut only what is absolutely necessary. 4. Protect your eyes with goggles. 5. Protect your clothing, as desired. 6. Clean up properly. 7. Spend time outside of class on a regular basis studying what you have seen in the lab. Be sure to answer any questions posed in the guide as you proceed. 8. It is a good idea to take at least one textbook back to the lab to reference diagrams and photos of the anatomical structures you are studying. 9. Remember that direction will be reversed in the pig. Its’ left is your right and vice versa. 1 Dissection Directions for the Fetal Pig External Anatomy 1. Put the pig into a dissecting pan and identify the four divisions of the animal body; a large compact head, a short neck, a roughly cylindrical trunk, with two pairs of appendages and a small short tail. What does the tail correspond to in humans? The trunk of the pig may be divided into the anterior thorax and the posterior abdomen. These two external regions correspond to two internal divisions of the trunk, the thoracic cavity and the abdominal cavity, to be studied below. 2. Measure the length of your pig in centimeters and determine its approximate developmental age using the chart. 2 3. In the head region observe the eyes, ears, nostrils, and mouth. Pry open the mouth and look for the tongue and teeth. Be careful, for the teeth are very sharp. 4. In the posterior region of the trunk, locate the anus. Note the gender of your pig by observing the location of the urogenital orifice. In a female it will be ventral to the anal orifice. In the male it will be just inferior to the umbilical cord. If your pig is a male, note the thin, cord-like, white penis just under the skin, stretching posterior. Be careful not to cut the penis as you begin your dissection. Note the presence of a scrotum on the male pig. It will probably contain testes. 5. On the ventral side locate the pairs of nipples. Since the pig is fetal, some structures are present that are not found in the adult. One such structure is the umbilical cord, extending from the ventral side of the body. Through it pass the vessels which carry nutrients and waste products between the fetus and the mother. Cut across the cord at a distance from the body, and attempt to identify the vessels in the cut end of the cord. There are two small umbilical arteries, which may be injected with red latex. Should they really be symbolized red? These arteries have much thicker walls than the single, large umbilical vein. It may be injected blue. Should it really be symbolized blue? There may be a very tiny, collapsed vessel, the allantoic duct. What was its function early in fetal development? 3 Survey of the Internal Organs 6. Put the animal on its back in the dissecting tray. “Hog tie” your pig by tying two separate strings to each of one front leg and one hind leg, using a tight knot to do so. Then pass the strings under the pan and tie to the other respective limbs, using a type of knot that you will be able to untie and retie tighter, as needed. 7. Using a scalpel, make a mid-ventral incision through the skin and the muscles of the body wall. Cut from the cervical region, proceeding posteriorly, to the region of the umbilicus. Then, cut around the cord on each side, being careful not to complete the circular cut, severing the penis of a male. Gradually deepen the incision you have made. Along your incision in the thorax, probe for the sternum. With scissors, insert the point into the area of the xiphoid process and cut through the length of the sternum up to the cervical region. At the axillary region proceed laterally with your incisions to the area just under the front foreleg. Note that it will be necessary to cut through ribs to do so. Make similar lateral cuts just below the ribs and in the lower abdominal cavity, just above the hind legs. Note that these cuts should be perpendicular to the mid-ventral incision. Left and right flaps of the body wall can now be turned out, exposing the thoracic and abdominal cavities. It will be necessary to crack or break ribs to open the thoracic cavity. In the abdominal region, a strip of skin bearing the umbilical cord will still remain in its original place. You will probably need to retie the strings attached to the limbs to take up any slack that may have developed while cutting the pig open. 4 8. Identify the diaphragm, a thin muscular partition separating the thoracic cavity from the abdominal cavity. In the thorax, examine the rib cage. Along its inner surface note the path of the ribs, each accompanied by a small artery and a thin white nerve. Note the lungs. How many lung lobes are there on each side? Is it symmetrical? How many lung lobes do you have on each side? Identify and feel with your gloved fingers the two pleural membranes. These are the thin, epithelial membranes which cover the lungs and line the inside of the ribs. The ones covering the lungs are called visceral pleura and lining the rib cage, parietal pleura. These membranes secrete a slick liquid. What might be a purpose for that liquid? Identify the heart, situated ventrally along the mid-plane of the thoracic cavity. Note that the heart is enclosed in a membranous sac, the pericardium. You may have partially torn this sack while cutting open the chest. 9. Now turn your attention to the abdominal cavity. Identify the liver, a large brownish organ lying just below the diaphragm on the pig’s right side. Note that the liver is divided into lobes. Notice that a large vein extends from the base of the umbilical cord, in the median strip of the body, going into the liver. This is the umbilical vein, already noted above. It originates in the placenta, passes through the umbilical cord, and leads into the liver. Why might we want blood coming from the placenta to enter the liver prior to going into the fetal heart and normal circulation? At its midpoint, cut through this vein. You should be able to somewhat reflect (pull back) on the median strip of the body wall, pulling it posteriorly. Attached to it on the sides are the two umbilical arteries. These branch off the aorta, taking fetal blood to the placenta. Between these arteries, attached to the median body wall strip, find the urinary bladder, which is banana shaped. Is your bladder shaped like this? 10. Underneath the liver, on the pig’s left and partially hidden by it, is the stomach. This is a large, whitish sac. The spleen is the elongated red body lying along the inferior curvature of the stomach. Is your spleen shaped like this? The small intestine is the long, convoluted tube which leaves the posterior end of the stomach and fills the right side of the posterior part of the abdominal cavity. The small intestine connects posteriorly with the large intestine (colon), a wider, less convoluted tube filling nearly all the remaining space in the abdominal cavity. It will probably be greenish in color. Gently lift up the loops of the intestine and find the kidneys on each side. They are reddish bean-shaped organs partly hidden by a filmy membrane, the periotoneum. This is a shiny, thin membrane which lines the entire abdominal cavity and covers the surfaces of the organs within it. 11. Focus your attention back to the liver. Lift it and look for the gall bladder on the right side. It resembles a deflated balloon and may be greenish in color. Notice that it has a thin, white line traveling down from it. This is the cystic duct. It carries bile which has been stored in the gall bladder. It unites with another duct 5 coming from the liver to form the common bile duct. This leads into the small intestine. These ducts are small, but usually the common bile duct can be seen. Once you are certain you have located the above, remove the liver from the pig, without destroying adjacent structures. To do this, sever the connections to the stomach, small intestine and diaphragm. As you cut between the diaphragm and liver, note the large blue blood vessel. This is the inferior vena cava. Note again that in the fetus the umbilical vein brings blood to the liver from the placenta. This blood is rich in food and possible toxins from the mother. After passing through the liver, the blood enters the inferior vena cava and is taken to the heart. In the adult, an umbilical vein is no longer present. A unique circulatory pattern involving a vein called the hepatic portal vein takes its place functionally. It brings food/toxin laden blood from the digestive organs to the liver. Place the liver in your baggie of pig parts. 12. Again, locate the stomach, immediately below the diaphragm, and find the point where the food tube, the esophagus, enters. At this point there is a donut-shaped ring of muscle called a sphincter muscle. It is known as the esophageal or cardiac sphincter. It has nothing to do with the heart. It is simply named as such due to the fact that it is close to the heart. This area of the stomach is known as the cardiac portion. The next part that bulges upward is the fundic region. The main enlarged stomach area is the body of the stomach. And, the final area that empties into the small intestine is the pyloric region. In this last region, look/feel for the sphincter muscle leading out of the stomach into the small intestine. It is called the pyloric sphincter. It should feel like a hard, roundish structure. Slit the stomach open. Expect some liquid and possibly some brown material to come out. Is this material food? Evert the stomach and look for the sphincter muscles from the inside. What do they resemble? 6 13. Once again, examine the spleen along the wide curvature of the stomach. In the area of the spleen and in the angle between the small intestine and stomach, find the pancreas. It is a not very compact, but rather lumpy looking organ. It somewhat resembles cottage cheese or a cob of corn. It may be possible to trace a small duct leading from the pancreas into the small intestine. It enters at about the same area as the bile duct. What does it release into the small intestine? 14. Examine the small intestine. It will appear as a mass of coiled tubes, mainly on the right side of the pig. It may be divided into three parts. The duodenum is the first portion. It leaves the pylorus and travels a short distance, basically straight, before passing into a highly coiled portion called the jejunum. The third and last portion of the small intestine, the ileum, is the portion where it joins the large intestine. Fan out a portion of the small intestine and look for a thin membrane, the mesentery, which helps hold the loops together. You will probably see faint pink arteries traveling to the intestine in this mesentery. It also contains nerves and veins, which are not easily seen. 15. Examine the large intestine. Find the juncture between the ileum and large intestine. You should find a greenish, blind-ended pouch held in place by mesentery. This is the caecum. This will enlarge as the pig grows and contains special bacteria that help digest cellulose. Do you have a caecum? What is the relationship between your appendix and your caecum? Can you digest cellulose? The large intestine continues as large loops, primarily on the left side of the abdomen. It finally continues dorsally and posteriorly down the pelvic cavity to form the rectum. It opens externally under the tail at the anus (anal orifice), surrounded by an anal sphincter. Once you are certain you have studied and understand the intestinal anatomy, carefully remove both intestines in one piece. Begin at the pylorus, cutting blood vessels and other membranes and connections as needed to do so. Place it in your baggie of pig parts. 16. Using the class torso, your book, etc. determine if your intestinal tract is set up in the same manner as the pig. If not, how is it different? Be sure to pay attention during class when your teacher shows you a length of string that matches the length of the total intestinal tract and try to reason why it has that length. 17. On your own body, can you point to the basic location of the following organs? Liver, gall bladder, stomach, spleen, kidneys, intestines, appendix Mouth, Nose, Pharynx and Neck 18. Cautiously deepen and lengthen the mid-ventral incision in the cervical area. Probe for the larynx or voice box, a white cartilaginous structure. Carefully free the larynx from the overlying skin, muscle and connective tissue to expose it fully. Just posterior to the larynx identify the thyroid gland, a pea-sized reddish body. It lies ventral to the trachea which is a stiff tube with rings of cartilage 7 leading from the larynx toward the lungs. The larynx is actually just a specialized portion of the trachea. What keeps the trachea from collapsing? At the end of class when you have removed your gloves and cleaned up, palpate your own neck to feel these cartilage rings. Carefully loosen the connective tissue and muscle in the neck area to expose the trachea to its full extent and to connect this dissection with the already opened thorax. Do not cut or tear any blood vessels passing through the neck. Lift the trachea with your blunt probe to expose the esophagus, a collapsed tube leading from the pharynx to the stomach. Why are there no cartilage rings in the esophagus like in the trachea? On either side of the trachea and extending down into the thorax and perhaps onto the surface of the heart, find the thymus bodies. They are loose lobes of tissue that somewhat resemble cottage cheese. They are found all along both sides of the neck. What are their function? Would you find thymus bodies like this in your body? In the body of an older adult? 19. Insert the tips of the scissors into the angle between upper and lower lips and cut through the cartilaginous jaw. Repeat on the opposite side. Then, carefully grasp the upper and lower jaw, being careful of the sharp teeth and pull to drastically dislocate the jaw. You will know you have pulled hard enough when a tiny flap of tissue, the epiglottis, pops up in the throat area. The floor of the mouth is occupied by the tongue. Small elevations are scattered over its surface, which contain the taste buds on their sides. In fetuses that are about ready to be born, small teeth are present. The roof of the mouth is formed by the bony hard palate anteriorly and the soft palate posteriorly. The soft palate forms a sort of curtain that separates the mouth or oral cavity from the posterior throat or pharynx. 8 20. A number of channels and passageways lead into or away from the pharynx. One of these can be found by gently probing behind the soft palate. This space is the nasopharynx, a cavity continuous anteriorly with the nasal passages. To examine the latter, cut transversely across the tip of the snout about 1 inch back from the nostrils. This will expose the nasal passages. Notice that they are separated by a sagittal partition of cartilage and bone, the nasal septum. Septum means “wall”. The floor of the passages is the hard palate. Along the lateral walls are large folds, the turbinate cartilages. What might their function be? Insert the scissors into one of the nasal cavities and cut posteriorly through the hard and soft palate. Probe along the length of this cut and examine the continuity between the nasal passage, nasopharynx and pharynx. 21. Depress the tongue down from where it is pressed against the roof of the pharynx. This will more readily expose the epiglottis, a median cartilaginous tissue that acts like a “trap door”. As food glides over it on its way from mouth to esophagus, it pushes down to cover the glottis, the opening into the trachea. This opening leads directly into the larynx. What will the action of this flap help to prevent? Insert your probe under the epiglottis into the glottis. Then, check in the cervical area to see if you are actually in the larynx. Next, insert your probe more dorsally, to just behind the glottis opening and you should be able to enter the esophagus. Once again, check in the neck area to see if you are actually in this food tube. Cut sagitally through the larynx and observe the interior cavity and fold-like vocal cords. The Heart and Blood Vessels A. Fetal Heart 22. Study the orientation of the heart in the thoracic cavity. Note any remnants of the pericardium that were probably cut earlier. If it still encloses the heart, carefully peel it and any needed connective tissue away. Note the auricles, dark flaps shaped like “elephant ears” that are the coverings over the atria. The ventricles form the bulk of the heart below the auricles. Note that the left ventricle forms into a point called the apex. It angles somewhat toward the left. Between the muscle of the ventricles is a groove that angles toward the right. It contains a very small coronary artery and vein complex of blood vessels. What are the functions of these vessels? What might occur if blood clots in these vessels, blocking blood flow? 9 B. Adult Heart 23. You will now complete the dissection of an adult sheep or cow heart. The purpose for this is to be able to see internal structures that are too small to see on the fetal heart. You will be given a separate dissection guide to complete this activity. Do not go on with the fetal pig dissection until you have successfully completed the adult heart dissection. Fetal Circulation and Blood Vessels (Use your textbook and diagrams to help locate the following blood vessels.) 24. Turn your attention once again to your fetal pig. Each of the four chambers of the heart has either a blood vessel entering or leaving it. Entering the right atrium, covered by the right auricle are two large veins that return blood from the body to the heart, the superior and inferior vena cavae. Probe around the top of the heart, more on the right side to find the superior vessel returning blood from the upper body and brain. Again, on the right side, probe more on the lower part of the heart to find the inferior vessel that returns blood from the abdomen and lower body. Both should be quite large and injected blue. Exiting from the right ventricle area and very ventral on the heart’s surface you should find the pulmonary artery. It may appear very white in color externally. This is due to the fact that artery walls are very thick. In an adult, where is this blood headed? Carefully lift the heart and lungs and rotate them gently toward the right. You may need to gently remove connective tissue to expose a thick white blood vessel, the descending aorta, very dorsal, pressed against the rib cage. This is carrying blood to the abdomen and lower body. Note tiny red arteries, the intercostal arteries, branching off this blood vessel. Where are they taking blood? Also note a tiny white structure parallel to each, which is a nerve, taking messages to the intercostal muscles for breathing. (There are actually intercostal veins present also. They will be difficult to see. In fact, all small veins can be hard to see, for veins are thinner walled and do not always inject well. Arteries with their thicker walls generally do inject well. This is true all over the body.) Trace the aorta anteriorly, looking under the pulmonary artery to find the aortic arch as the aorta leaves the left ventricle. Where is the blood in the aorta headed? How many smaller arteries do you see branching from the aortic arch? There should be two. How many branch from the aortic arch in your body? We shall not attempt to locate the pulmonary veins in the fetal pig. They 10 are difficult to find. But, you should review where they are coming from and into what chamber they empty their blood. 25. Remembering that veins are thin-walled, small, tear easily and do not inject well, we shall focus more on finding a few major arteries in the fetal pig. Once again, locate the pulmonary artery. Trace its path to notice that it travels through a thick temporary, fetal vessel, the ductus arteriosus to empty the majority of its blood into the aorta. This vessel is found only in the fetus, in which it bypasses blood around the nonfunctional lungs. Instead of going to the lungs, the bulk of the blood from the right ventricle passes directly into the aorta and then is distributed to the body. What effect does this have on blood gas levels in the fetal body? At birth, the ductus shrivels and seals off. At the same time, the foramen ovale that you learned about opening between the two atria, also seals off. From that time onward, the circulation will become like the adult, with right ventricle blood going to the lungs where it is oxygenated. You should be able to gently remove connective tissue near the ductus to find one of the branches from the pulmonary artery that will carry blood to the lungs in the future. The fetal condition is advantageous because the placenta and umbilical cord, not the lungs, supplies the fetus with oxygen. 26. Now turn your attention once again to the aortic arch and the two arteries branching from it. The one that is on the left is the left subclavian artery. As best as you can, carefully removing connective tissue as needed, trace it as it carries blood to supply the left forelimb (arm). Why is it named the subclavian? The branch on the right is a “combo” artery called the brachiocephalic artery. Why is it named as such? It has three smaller arteries branching off of it. We shall attempt to locate them. It supplies both sides of the brain with two branches off of it, the right and left carotid arteries. To expose these vessels as they leave the brachiocephalic artery, it may be necessary to cut away two veins, the brachiocephalic veins that are draining blood from the head and upper arms. They drain into the superior vena cava. (Note that there is symmetry in terms of the vein arrangement but not in the arteries.) You may or may not have well injected brachiocephalic veins. If they are well injected, see if you can remove connective tissue in the neck and expose the jugular veins that drain into them on each side of the neck. These drain blood from the brain. You should be able to locate the jugular veins even if your brachiocephalic veins are poor quality. All of these veins will be injected blue. Alongside the jugular veins will be the red injected carotid arteries. Gently remove connective tissue tracing these vessels back to the brachiocephalic artery that branches from the aortic arch. Here is where it may be necessary to actually remove the brachiocephalic veins in order to see the carotid arteries branching from the brachiocephalic artery. After you have located the carotid arteries, see if you can locate the third and final branch off the brachiocephalic artery, the right subclavian. Trace it as far as you can to see how it passes under the (broken) clavicle to supply the right forelimb (arm). 11 27. Using your textbook as a reference, in your notebook, make quick sketches of the major arteries learned above. Use red to symbolize their blood. Draw one sketch of a pig and a second to show how it differs in your body, the human. Also, make a quick sketch of the major veins learned above. They are the same for pigs and humans. Use blue to symbolize their blood. 28. After you have cleaned up, gently palpate the sides of your neck, one at a time, to see if you can feel the blood traveling in your carotid arteries to supply your brain. What would happen to the brain if a blood clot ever blocked the flow of blood to the brain? The Thorax 29. Once you are completely certain you can locate all the required cardiovascular structures, you will remove the heart and place it in your pig parts bag. To do so, cautiously cut through the large, major blood vessels near the heart to remove it from the pig. Once again, identify the large aortic arch that continues posteriorly as the descending dorsal aorta. It is the large, median vessel just ventral to the vertebral column. It has two divisions based on location. The part that is in the thorax is called the thoracic portion and the part in the abdomen is the abdominal portion. 12 30. Locate the bottom of the trachea near the top of the lungs. The trachea branches into two smaller tubes, the right and left primary bronchi (bronchus). To locate these use your scapel placed horizontally and flat and begin to very gently scrape away lung tissue. Continue to do so gently until you see where the trachea bifurcates (branches) into the bronchi. Once you find the bronchi, continue to gently scrape to see if you can expose where the primary bronchi continue to branch into secondary bronchi. You will not be able to see it, but these secondary bronchi branch again and again into smaller and smaller tubes, the tertiary and quaternary bronchi. Eventually these branch into bronchioles at ends of which are the air sacs called aveoli (alveolus). These are capable of great distention after birth when the fetal pig begins breathing on its own. They are surrounded by capillary networks (beds) that branch from the pulmonary artery and drain into the pulmonary vein. They are so thin walled, they allow for very easy gas exchange. 31. See if you can locate the esophagus in the thoracic cavity and trace how it pierces through the diaphragm to enter into the stomach via the esophageal sphincter. Where does the esophagus lie in relation to the heart? Why does gastric esophageal reflux disorder (GERD) result in “heart burn”? The Abdomen and Abdominal Arteries and Veins The Excretory System 32. Once again, locate the kidneys. They lie against the dorsal wall of the abdominal cavity. Remember that they are behind the abdominal membrane called the peritoneum. Gently remove this peritoneal covering from the kidneys. Locate the abdominal portion of the descending aorta. It will be slightly to the left of the median plane. It will be thick and white in color. Locate the inferior vena cava. It will be less thick, blue in color and slightly to the right of the median plane. Near the superior surface of the kidneys, try to locate the adrenal glands. They will be small and shaped like half moons. They will press closely to aorta on the left and the inferior vena cava on the right. They look like a little “hat” worn by the kidneys. To what body system do they belong? What is their function? Locate a depressed area, the hilum on each kidney. This is where the blood vessels and tubes carrying urine enter and exit the organ. Identify the urine carrying tube exiting at the hilum called the ureter. Gently remove the peritoneal membrane covering it to fully expose it. Trace it down to where it enters the urinary bladder. In order to see it you may need to gently push aside the umbilical arteries that lie alongside the urinary bladder on their way out of the umbilical cord. 33. In the abdomen, once again locate the abdominal portion of the descending aorta. Carefully remove the peritoneal membrane to see if you can find the red renal artery coming off the aorta, carrying blood to be “cleansed” into the 13 kidney. Parallel to this you should find a blue renal vein bringing “cleansed” blood out of the kidney. This vein should merge into the inferior vena cava. The Excretory and Reproductive System 34. Review step # 3 above as to how to determine the gender of your pig. After you have studied the reproductive system, your teacher will demonstrate prosected (already dissected) male and female reproductive anatomies on pigs. Be sure you observe both genders. 35. If desired, you may attempt to dissect and expose the reproductive system of your pig. The female is easier to do than the male. Proceed to the appropriate directions for your pig below. In all of the following directions, proceed with extreme caution. Most of the structures to be studied are small and delicate and covered by the pelvic pubic symphysis. They are easily destroyed if the dissection is not carried out with careful precision. Do not be upset if you make mistakes. It is easy to do! Female 36. Feel for the pubic symphysis, the mid-ventral juncture of bones of the pelvic girdle between the hind legs. Precisely along the mid-line in this region, cut skin and muscle until the bony pubic symphysis is exposed. With your scissors cut through the pubic symphysis along this mid-line, making sure that underlying structures are not damaged. Carefully chip and pick away small pieces of bone and only bone to the right and left, so that a better view of the underlying parts can be obtained. You may also find it helpful to retighten the string which holds the hind legs apart. 37. Turn your attention once more to the ureters. Trace them once again to where they enter the bladder. Carefully pick away at connective tissue as needed to be able to see them enter the urinary bladder. They will enter near the base of the bladder as it sits naturally in the pelvic cavity. Note how the bladder narrows at the top. This is the area where the embryonic allantoic duct exits to carry urine out of the umibilical cord. Remember that this duct collapses and becomes nonfunctional as the fetus develops. In the embryo urine passes from ureter to bladder to allantoic duct to umbilical cord. As it matures and is born, urine must travel out of its body via the urethra. To find this tube, once again look at the base of the bladder near where the ureters enter. Here the bladder narrows into the tube comprising the urethra. Since your pig is female, the urethra will continue straight posteriorly to exit out of the urogenital orifice under the tail and anus. Where it exits you will find a small pointed structure, the genital papilla. 38. In the pelvic cavity, locate the ovaries. These are very small, egg-shaped bodies. The oviducts or fallopian tubes are very small only about 1mm and very hard to 14 see. These lead into the uterine horns which are highly twisted or convoluted sack-like tubes. These provide the area for development of multiple fetuses. Removing connective tissue delicately, as needed, locate where the two horns fuse. This is the uterine body. The fetuses must pass into here to be born. The uterine body constricts to form a neck or cervix, which leads into the vagina. The vagina can be located by gently lifting the urethra to the side. Note how the urethra and vagina fuse to form one tube, the urogenital sinus which leads to the outside urogenital orifice. As a young female pig matures into an adult, the vagina and urethra gradually form into separate tubes to exit out of the orifice. This resembles human females. Thus, reproductive processes and metabolic wastes travel in separate paths, a condition which differs from that in the adult male of both species. Male 39. This part of the dissection is very complex. Again, do not expect to get it perfect. You will probably make some mistakes. Be sure to see the prosected pig demonstrated by the teacher for help in doing your dissection. Review the location of the penis just under the skin of the abdominal wall. Just inferior to the umbilical cord you will find the urogenital orifice. This is the opening from which the penis can protrude for urination or sexual intercourse. The penis is a thin, white cord, just under the pelvic area skin. It contains the urethra which carries urine from the bladder. The portion of the penis you can see under the skin could be termed its “external” portion. The penis is actually about twice that 15 length. As it travels posteriorly toward the tail, it curves 180 degrees to dive under the pubic symphysis bone of the pelvis. This portion could be termed its “internal” portion. This portion will contain the urethra carrying urine from the bladder and that same urethra will also contain semen with sperm and fluids. However, this never occurs at the same time. 40. Turn your attention once more to the ureters in the abdominal cavity. Trace them once again to where they enter the bladder. Carefully pick away at connective tissue as needed to be able to see them enter the urinary bladder. They will enter near the base of the bladder as it sits naturally in the pelvic cavity. Note how the bladder narrows at the top. This is the area where the embryonic allantoic duct exits to carry urine out of the umibilical cord. Remember that this duct collapses and becomes nonfunctional as the fetus develops. In the embryo urine passes from ureter to bladder to allantoic duct to umbilical cord. As it matures and is born, urine must travel out of its body via the urethra. To find this tube, once again look at the base of the bladder near where the ureters enter. Here the bladder narrows into the tube comprising the urethra. Since your pig is male, the urethra will continue straight posteriorly to enter the penis. Then, as described above, the penis continues under the bony pubic symphysis, then curves 180 degrees to lie just under the skin to exit under the umbilicus via the urogenital orifice. 41. Carefully remove the skin from the “external” penis to expose it as a white cord-like structure. Next turn your attention to the scrotum. Testes begin their development in the pelvic cavity in about the same location as the ovaries, just inferior to the kidneys. Prior to birth they descend into the scrotal sac to be suspended there by a thin cord, the spermatic cord. Why must they descend into the scrotum? Since your pig was close to being born, the testes are most probably already descended into the scrotum. Gently palpate the scrotum to see if they are descended. Turn your attention to the pelvic cavity to see if you can locate the spermatic cord. It will be a very thin, pinkish cord branching from the aorta to travel down toward the testes. It contains an artery, vein and nerve to supply the testes. It may be necessary to carefully extend cuts of the pelvic wall through skin and muscle posteriorly at this time. . 42. Once again at the scrotum, carefully feel for a teste and slice open the scrotum to reveal the teste. It will be a somewhat gelatinous, bulbous structure with a thickened white cord leading upward. On top of it you will find the epididymis, a hardened bean-like structure, where sperm is stored and gains its flagellum for locomotion. Gently tug on the spermatic cord in the pelvic cavity and note the movement of the teste upwards. 43. Leading out of the teste, carrying sperm up and into the body, you will find a somewhat flattened, white tube, the vas deferens. Once again, look in the pelvic cavity and locate the spermatic cord. You will find the vas deferens right next 16 to it, traveling through a hole, the inguinal ring in a thickened, transverse, band of tissue, the inguinal ligament. It is through this hole that the testes, once in the pelvic cavity, must descend in order to be suspended in the scrotum. You should observe that the vas deferens loops over the ureter to enter into the base of the bladder where the urethra exits. It is here that sperm is placed into the urethra which continues into the penis. Carefully lift the bladder at this point, to more fully expose the location where the vas deferen tubes enter. On the dorsal side of the urethra, locate a small, roundish body, the prostate gland. It may be partially concealed by the seminal vesicles, a pair of fairly large, lobulated glandular bodies, one lying along each side of the urethra. Both the prostate and seminal vesicles secrete fluids which contribute to the formation of semen. Try to expose all of this anatomy carefully on one side of the pig’s body. 44. On the other side of the pig’s body, slightly lateral of the medial line of the body, begin to make a deep incision starting in the pelvic cavity, near the inguinal ring. Gradually deepen the incision to actually cut through pubic bone, using forceps to pick out pieces of the bone and tissue. It will be a difficult and complex dissection. Don’t expect to get it perfect. As you deepen the incision, pay attention to the external portion of the penis that you have skinned and attempt to trace it as it dives under the pubic bone. Try not to damage underlying structures. You may find it helpful to retighten the posterior strings holding the pig’s body at this time. If you have been careful, you should be able to locate and trace the penis/urethra under the pubic bone, up to the bladder. In this area, lying alongside it, you will find two banana-shaped structures, the Cowper’s or Bulbourethral glands. These contribute to semen by secreting what is termed the pre-ejaculate. It provides some lubrication for intercourse. Again, see if you can locate the prostate gland and seminal vesicles. 45. It should be clear from your dissection of the male that the urethra serves to conduct both semen and urine, but not both at the same time. Remember that this arrangement differs from the adult female, where separate ducts eventually form for urinary and reproductive purposes. Be sure to observe and study both genders of pigs. 17 46. This completes the fetal pig dissection. To prepare for the exam, spend time as needed reviewing in the lab. Study the different systems by using your text, on-line power points and notes and suggested Internet study links from the instructor’s webpage. Be ready to properly clean up and dispose of your group’s specimen after the exam as directed by the instructor. 18