one college store's pilot project maps the challenges, risks, and

advertisement

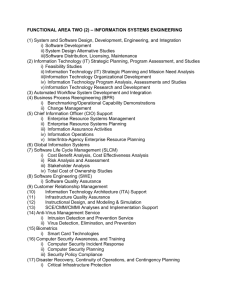

Driving Licensing ONE COLLEGE STORE’S PILOT PROJECT MAPS THE CHALLENGES, RISKS, AND REWARDS OF INTRODUCING ACADEMIC CONTENT LICENSING TO A CAMPUS. by Michael von Glahn I nstitutional licensing, either campuswide or on a by-course basis, is still in its early days, on campuses primarily as pilot projects. But as more studies confirm that up to half of all college students forgo purchasing at least some of their course materials due to cost or other factors, institutions are looking at licensing as a way to ensure all students have the necessary materials to succeed academically. Under this model, the institution and publisher negotiate a set price for the materials, which can be significantly discounted because the publisher is guaranteed a sale to every student enrolled in the course. Students pay a mandatory course materials fee, either separately or bundled into their tuition. Some worry that licensing will cut the college store out of the channel, with publishers getting content to students directly through an institution’s learning management system. But stores can remain part of the process, especially if they move proactively to insert themselves into any discussions about licensing, or even start those talks themselves. Guidance is available from a NACS white paper, released in April, that reflects the work of the NACS Content Licensing Task Force. Academic Content Licensing: Concepts and Considerations for a New Course Content Model and related resources are available for free in the Hub Global Library at: http://thehub.nacs.org (Course Materials folder). SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 Managers and directors need to discover if any stakeholders on their campus are already exploring the licensing option, either independently or after being approached by a publisher, and get themselves a seat at that table. “We found a good place to ask around is where the course material requirements are determined by faculty committee section process, where large classes have potential for sectioning control groups for benchmarking comparisons, and where there is large-volume sales potential to attract vendor participation,” says Chris Tabor, general manager, Queen’s University Campus Bookstore, Kingston, ON, Canada. Tabor notes that at Queen’s, “the faculties with the courses with enrollments over 1,000 students explored the blended options before most others.” Be aware of the politics involved, as many administrators worry that licensing could be seen as a tuition increase, which for many institutions can only be undertaken via legislation. Faculty must be assured that they will retain the freedom to choose their own course materials and that content’s format. “In my own analysis of the different schemes underway,” says Tabor, “it seems to me that the faculty are genuinely interested in superior pedagogy, admin is interested in superior admin, and our students remain interested in what they NACS | The College Store Magazine 61 Driving Licensing continued have always been interested in: a good education at the most reasonable cost.” THE ROADBLOCK THAT WASN’T Inspired by the NACS task force and its white paper, UC Davis Stores, University of California, Davis, adapted ideas from both to fit its campus. Director Jason Lorgan, who sat on the task force, approached the five largest publishers on his campus after making sure they all offered appropriate product. He ended up working with McGraw-Hill, Pearson, and Cengage. The pilot concentrates on large-enrollment undergrad classes ranging from about 300-1,600 students. In all, about 4,500 students will be involved. To find out what policies he’d have to navigate to charge a new fee, Lorgan went to the school’s website and began searching relevant keywords. He very quickly found the pertinent portion of the massive UC Davis policy manual: Chapter 330, Section 86. Two items presented potential problems. One stated, “The fee may not exceed $65 for courses with a maximum actual cost of $160 per student, and may not exceed $80 for courses with an actual cost of $161 or more per student.” Lorgan expected some of the materials would cost more, which he assumed would be an issue. Another Model: E-Texts in Texas In 2011, Texas Gov. Rick Perry challenged Texas universities to develop $10,000 baccalaureate degrees with textbooks included. In January 2014, Texas A&M University-Commerce and South Texas College rolled out their joint response: new bachelor’s of applied science degrees in organizational leadership developed with the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board. The online-only program lets students advance through lower-division coursework as soon as they demonstrate mastery of a concept, even if they’re already at that level on the first day of class. The cost of $750 for each seven-week period includes the cost of e-textbooks. Wit Within that time span, students are allowed to complete as many courses as they can without being subj subject to a change in price. A score of 80 is require to pass each course. required The planners say students entering the program progra without college credit should be able to complete th the degree in about three years for a total cost $13,000-$ of $13,000-$15,000. Someone who enrolled already having 90 credit hours, as an example, could wrap up degree in a year for about $4,500-$6,000. the degre Although the program started with only a handful of students, the partners have stated they expect to have 3,000-5,000 aboard within five years, especially veterans and mid-career professionals. 62 The College Store Magazine | NACS “Our students remain interested in what they have always been interested in: a good education at the most reasonable cost.” —Chris Tabor, general manager, Queen’s University Campus Bookstore The other possible stumbling block was an item declaring that “course textbooks are not included in the course materials and services fee.” Viewing any policy manual as a living document, Lorgan set up a meeting with an associate dean and a representative from the school’s Department of Budget and Institutional Analysis to explain the pilot and argue that the school’s policies needed updating. He assumed changes would be needed to raise the fee limit and move textbooks under the course materials and services fee umbrella. “Boy, was I wrong,” he says. Instead, he was told that the second item applied even to digital textbooks, which meant his project wasn’t subject to the first item. “What we thought was going to be a roadblock for us actually turned out not to be at all,” he says, adding that he encourages other college stores to stop falling back on “Policy forbids me” or “My campus doesn’t allow this” as reasons not to explore new models. “To me, that just sounds like a terrible excuse,” he says. “If you go to people and say, ‘This policy is preventing us from saving our students significant amounts of money,’ usually you get a much different reaction, a very positive reaction.” However, in addition to their positive reaction, the higher-ups had some bad news: “The manual basically says things have to be done a year in advance and you’ve got to get everyone and their mothers’ permission,” Lorgan says. As a public institution, no one at the school can implement mandatory fees without going through a complex, laborious process. But they also suggested the project could skirt the bureaucratic maze if Lorgan could tweak things so the fee wasn’t 100% mandatory. So the opt-out option was born. A WAY OUT AS A WAY AROUND Everyone enrolled in the pilot courses will receive access codes by email about two weeks before the quarter begins, giving them free access to the course content until the add/drop period ends two weeks into the quarter. The materials are adaptive content—technology that’s gotten very positive feedback from students who’ve used it—not SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 REAL PRICE EXAMPLES FROM THE UC DAVIS PILOT National Print Text + Digital Access Price COURSE Management 11A $306.00 Management 11B Human Development 12 UC Davis Digital Price with Print Upgrade Difference Savings $95.00 $211.00 68.95% $463.00 $95.00 $368.00 79.48% $173.65 $127.50 $46.15 26.58% Math 21A $295.65 $95.00 $200.65 67.87% Physics 9A and 9B $267.60 $130.00 $137.60 51.42% Physics 9C $267.60 $75.00 $192.60 71.97% Source: Academic Content Licensing for College Stores, presented at the California Association of College Stores Course Materials Summit 2014 e-textbooks, which have had much poorer reviews. In theory, since the students already possess the materials, they won’t try to find them elsewhere. “We have negotiated really outstanding pricing that we believe they can’t find anywhere else.” Lorgan says. “The publishers have given us prices that’re lower than what’s on their own website and it’s much lower than anything you can find on Amazon or anywhere else.” Once the opt-out was added, Lorgan met with his boss and his boss’s boss, then the vice chancellor of student affairs, to whom the store ultimately reports. Each gave the project a green light. By avoiding the mandatory-fee hurdle, the opt-out was critical for approval. A print option was also built in because Lorgan assumed it would be needed as a bridge until faculty became more comfortable with digital content. However, at the last few meetings with faculty no one mentioned print. “The most difficult part of the program is the print upgrade,” he says, “and it may have been an issue that we created that wasn’t really an issue for others.” Students who opt for print will in most cases get what Lorgan calls “a no-frills, low-cost, black-and-white, threehole, shrinkwrapped kind of thing.” The store’s cost will be $20-$25, and it will sell for $25-$30. On the digital side, the publishers will provide the access codes without charge because, in essence, they have no value until they’re activated, just like a gift card. Once the add/drop period is over and the number of enrolled students is final, the publisher bills the store, which charges the students. The print option presented one potential problem: What if a student bought the $25 book and then opted out of the digital material? The low print pricing is based on the assumption those buying it have already paid for the digital content. Lorgan worried word would spread that if you opted out of the digital you could get a print book dirt-cheap. Store signage and information printed on each book will make clear that anyone who tries that will find an upcharge on their student account. The store’s point-of-sale system will capture the student ID number whenever a print version is sold. That info will be compared to the opt-out list. A spreadsheet listing everyone who opted out will be sent to the publishers so those students’ access codes can be deactivated. “So they’ll never have been charged, but their access will have been turned off,” explains Lorgan. “There’s no savings SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 This flier promoting UC Davis Stores’ licensing pilot helped spread the word across campus that student success and reducing the cost of academic content are the store’s goals. Another Model: Minis at Lynn Lynn University, Boca Raton, FL, launched an initiative in 2013 to provide students with required core curriculum in e-book form to save them money. Students receive an iPad mini they can use to download free faculty-produced iBooks and access other course materials via iTunes U. Lynn claims extravagant savings, citing the example of “an average first-year business student” being able to spend only $29 on materials vs. $938 for new, hardcover textbooks. p in students’ The program’s first year saw about 750 iPads put hands, with that total expected to hit 1,800 in 2014-15. The school says it hopes to reach 100% delivery within one or two years. The program was expanded this fall to include all new freshmen and transfer students, all day undergraduate students, and all new MBA and Ed.D. students. NACS | The College Store Magazine 63 Driving Licensing continued to opt out and get the print book. You will basically pay the same price. If the digital part was $75 and the print part was $25, if the student opts out, if they take the print book for $25, we’re going to do an upcharge of $75.” With no idea how many students might opt for print, the store will start with a low order, probably 25% of enrollment. Lorgan says he’s not worried if print copies take a week to come in, because students will already have digital access to the material. He estimates those in the pilot will save an average of 70%-80% on their materials. Surveys conducted after a spring 2013 Educause/Internet2 licensing pilot at the University of Missouri indicated 42% of students would support paying a required fee only if it saved them 80% or more, so Lorgan’s estimate is in the right ballpark. SURPRISINGLY WILLING PARTNERS Although Lorgan went in expecting perhaps 10% of the faculty he approached to sign on to participate, in the end only one instructor didn’t agree to the proposed model. The sole faculty holdout wanted a different format for the pilot, with students opting in rather than opting out. “There’s a hardcover textbook on the shelf like always,” Lorgan explains, “but if a student wants digital they can opt in and we would give it to them at a really low price.” He doesn’t think that’s the best model for the future, but agreed to test it for that one course. Lorgan notes that in his 21 years in the industry, working most of that time as a textbook manager, he’s never gone into a faculty office with a publisher as part of a sales call. “Now, we’re going in with the publisher and we start on offense with price. We’re so often in defense on price,” he says. “The publishers have given us prices that’re lower than what’s on their own website and it’s much lower than anything you can find on Amazon or anywhere else.” —Jason Lorgan, UC Davis Stores Another change is the switch in focus from by-unit to by-course. “I would say, ‘OK, last quarter I made $1,000 on this course,’ and the publisher would say, ‘I made $2,000 on this course.’ That’s our baseline, so our goal is to make more than that on this course obviously,” he explains. If he wants to make $2,000 instead of $1,000, he takes that $2,000 he wants in margin and divides it by 90% of the enrollment. “That’s the number we’re using,” he says. “We think 10% are going to opt out, we think 90% are going to stay in. That’s a radical sell-through increase where the publisher’s willing to negotiate.” In every case, he adds, the margin the store is adding to the book is “very, very small compared to our traditional 25% margin. Yet we’re making significantly more per course. When you go to a publisher and say, ‘I sold 20 last term, I’m going to sell 20 this term, Please give me a discount,’ that’s a nonstarter conversation. But when you Blow Your Horn John Wierson, textbook buyer, Iowa State University Book Store, Ames, attended the Digital Content Product Institute held last June at NACS headquarters in Oberlin, OH, hoping to gain some insight from representatives of five of the major publishers on whether the steady 3% annual increase in digital textbook sales his store has tracked might accelerate. What struck him at the institute was the evident willingness of retailers and publishers to work together to provide less expensive options, such as licensing pilots. His store is involved in a pilot this fall for three courses. “A few years ago, many were concerned that if digital took off it would happen through the institutional model, where licenses were purchased through the university, leaving the bookstores out,” Wierson says. “Today, it feels like many stakeholders, including publishers, are seeing that the bookstore can be the distributor for digital content.” But to be that distributor you have to promote your mission and your availability to other major players, both on and off campus. Wierson 64 The College Store Magazine | NACS “You are the expert in course materials and you need to make sure everyone knows it.” —John Wierson, textbook buyer, Iowa State University Book Store, Ames suggests arranging meetings with the provost or someone in the provost’s cabinet, as well as with the student body government. Try to make presentations at faculty senate or president’s council meetings, too. “You are the expert in course materials and you need to make sure everyone knows it,” he says. He adds that the academic mission shared by the store and the institution must remain prominent: “Although much of it has to do with price point, we cannot lose sight of the fact that many of the digital products—if utilized by the instructor—can increase the students’ ability to learn.” SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 go and you say, ‘I sold 20 last term, I’m going to sell 90 this term,’ they’re extremely willing to negotiate. To be honest, it kind of shocked me how much they’re willing to go down.” THE THREE YEARS ARE FINALLY UP Lorgan says he’s been “a huge digital skeptic for a really long time, so it’s kind of ironic that I’m charging full force into digital right now.” When he started in collegiate retail, his first boss claimed digital textbooks were three years away from going mainstream. “That was in 1993,” he recalls, “so I used to tell the joke, ‘Digital textbooks have been three years away for the last 20 years.’” In his opinion, academic e-book sales have already peaked. “It’s just a substitution technology,” he says. “It’s really just going from a piece of paper to the screen, but the content isn’t educationally superior in any way. … We’ve heard from students that if that’s how it is, they prefer print, and you’ve got to listen to your customer.” Survey results support him, consistently showing that while students may be fine with e-books for general reading, it’s not a format they like for course content. The University of Missouri tested a pilot of its own in fall 2013, using MBS Direct and several publishers. Even though offered free or reduced-price e-textbooks, many students ended up using print versions found elsewhere. Lorgan has heard from customers and from his own student workers who’ve used adaptive content that they’re disappointed now if they go into a new term and their course materials don’t include it. “We never heard that in the past,” he says. “If there was an access code, it was nothing but complaints.” Now, students look for the codes because the adaptive content has helped them in the past. Lorgan says he believes that means the elusive tipping point for digital has finally been reached. THE COLLEGE STORE ADVANTAGE Another licensing pilot is also underway at UC Davis, spearheaded by the school’s library and academic technology services and using the Courseload platform (www.courseload.com). When he heard about it, Lorgan talked his way onto the project committee. Because the library doesn’t have delegated authority on campus to deal with course materials the way the bookstore does, the project faces many more hoops to jump through before it can charge a fee for content. “That basically means it is bogged down in this massive bureaucracy that is higher education,” says Lorgan. A highly placed administrator told him it would be a miracle if that pilot ever gets out of committee. College stores are compliant with credit-card industry standards, can handle cash transactions, and can often bill students’ accounts and third parties such as Veterans Affairs. Stores need to use the advantages they have over other campus stakeholders that might be looking at licensing. Lorgan says starting the conversation doesn’t need to be as massive an undertaking as even NACS’ white paper makes it seem. SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 “Where it talks about basically every single solitary office on campus is a possible place you have to go, I don’t know a human being who wouldn’t be intimidated by that,” he says. “I’m trying to send the message: Don’t make it more complicated than it needs to be. Involve as few departments on campus as you think is possible.” UC Davis starts school this fall Oct. 2, a week later than normal. “Hopefully it’ll be great news at that point,” Lorgan says. He’ll present a session on his initial outcomes at CAMEX 2015 in Atlanta. Even without results yet, though, the pilot effort has paid dividends. “It has already been a huge success in building our credibility on campus as digital leaders who are challenging the way content has been historically delivered,” Lorgan says. “This may be the perfect opportunity for stores to create a CS win-win for publishers, stores, faculty, and students.” Q Michael von Glahn is editor of The College Store magazine. No Model’s Perfect There are, of course, some caveats regarding licensing academic content, and college stores would do well to be aware of them as objections that might be raised in any stakeholder discussions. Even with the reduced price tag the licensing model offers, some students may believe they can do better on their own by employing lower-cost or free options such as sharing or borrowing a book, or even doing without. In the comments section following one online story about licensing, a student wrote, “Currently, my printed textbooks cost about $140 each. I have several per quarter. At the end of the quarter I can average the resale for the book at around $100 per book. That is great! But e-books for my Kindle for the same book are around $120 per book. That sounds like a savings of $20, but I can’t resell the electronic copy. That is a loss to me.” There is also the specter that once licensing helps publishers minimize the used-book market and remove the incentive for illegally downloading copies, they will be free to start jacking up content prices. “If colleges and universities have been unable to prevent even greater price increases when they switched to a similar publisher digital-subscription model at libraries, what evidence exists that this can succeed here?” asks Rich Hershman, NACS vice president of government relations. He also points out that about half the states that collect sales tax on course material transactions—including California, Texas, Indiana, and Florida—will lose tax revenue that funds colleges and universities if the schools switch to a fee model. “True, that represents savings for students,” Hershman says, “but not without cost to state and county budgets and higher-education funding that must be factored into such programs and state funding.” NACS | The College Store Magazine 65