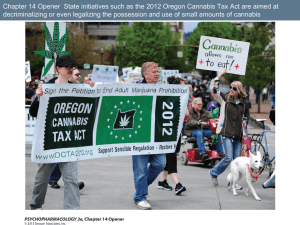

ASAM Medical Marijuana Task Force White Paper

advertisement