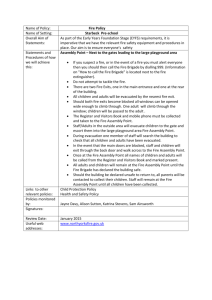

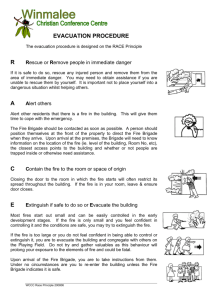

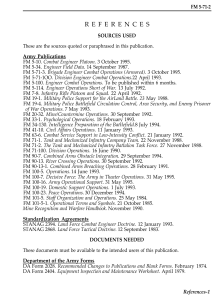

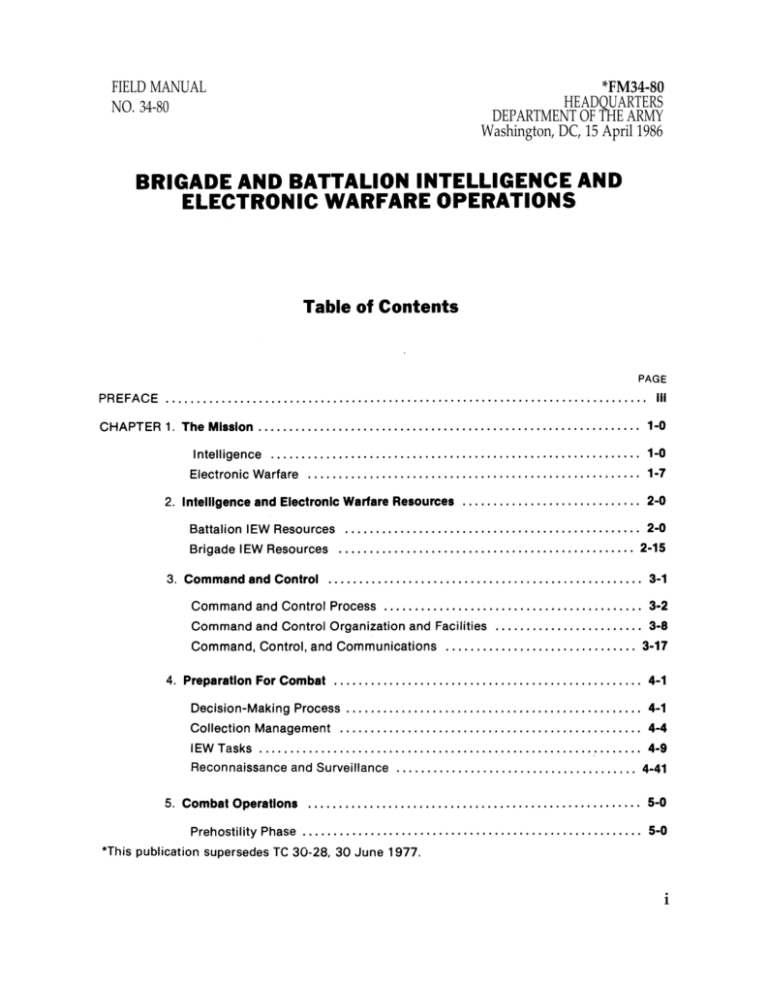

Brigade and Battalion Intelligence and Electronic Warfare

advertisement