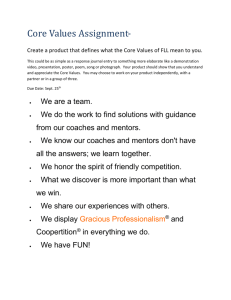

cultural elements community defined evidence

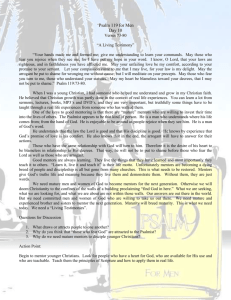

advertisement