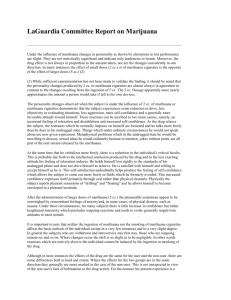

Regina v. Parker - Drug Policy Alliance

advertisement