MMA II 2012 - Alger County Courthouse.

advertisement

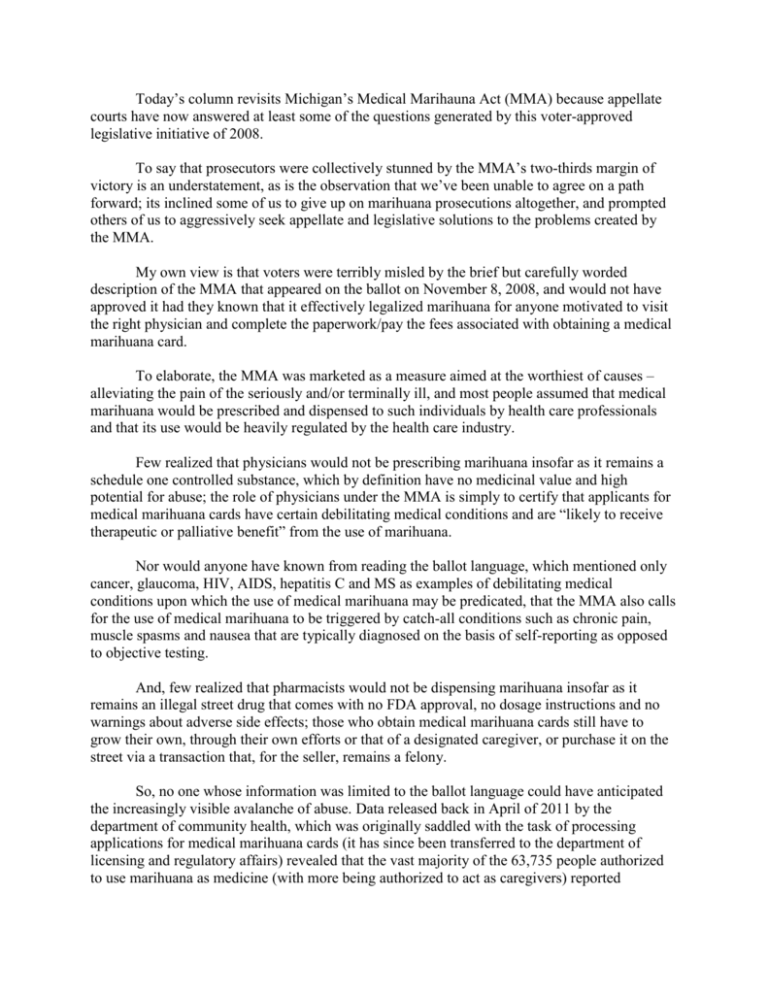

Today’s column revisits Michigan’s Medical Marihauna Act (MMA) because appellate courts have now answered at least some of the questions generated by this voter-approved legislative initiative of 2008. To say that prosecutors were collectively stunned by the MMA’s two-thirds margin of victory is an understatement, as is the observation that we’ve been unable to agree on a path forward; its inclined some of us to give up on marihuana prosecutions altogether, and prompted others of us to aggressively seek appellate and legislative solutions to the problems created by the MMA. My own view is that voters were terribly misled by the brief but carefully worded description of the MMA that appeared on the ballot on November 8, 2008, and would not have approved it had they known that it effectively legalized marihuana for anyone motivated to visit the right physician and complete the paperwork/pay the fees associated with obtaining a medical marihuana card. To elaborate, the MMA was marketed as a measure aimed at the worthiest of causes – alleviating the pain of the seriously and/or terminally ill, and most people assumed that medical marihuana would be prescribed and dispensed to such individuals by health care professionals and that its use would be heavily regulated by the health care industry. Few realized that physicians would not be prescribing marihuana insofar as it remains a schedule one controlled substance, which by definition have no medicinal value and high potential for abuse; the role of physicians under the MMA is simply to certify that applicants for medical marihuana cards have certain debilitating medical conditions and are “likely to receive therapeutic or palliative benefit” from the use of marihuana. Nor would anyone have known from reading the ballot language, which mentioned only cancer, glaucoma, HIV, AIDS, hepatitis C and MS as examples of debilitating medical conditions upon which the use of medical marihuana may be predicated, that the MMA also calls for the use of medical marihuana to be triggered by catch-all conditions such as chronic pain, muscle spasms and nausea that are typically diagnosed on the basis of self-reporting as opposed to objective testing. And, few realized that pharmacists would not be dispensing marihuana insofar as it remains an illegal street drug that comes with no FDA approval, no dosage instructions and no warnings about adverse side effects; those who obtain medical marihuana cards still have to grow their own, through their own efforts or that of a designated caregiver, or purchase it on the street via a transaction that, for the seller, remains a felony. So, no one whose information was limited to the ballot language could have anticipated the increasingly visible avalanche of abuse. Data released back in April of 2011 by the department of community health, which was originally saddled with the task of processing applications for medical marihuana cards (it has since been transferred to the department of licensing and regulatory affairs) revealed that the vast majority of the 63,735 people authorized to use marihuana as medicine (with more being authorized to act as caregivers) reported unspecified ailments causing chronic pain, muscle spasms and nausea. Cancer was the most frequently cited of any specific ailment, yet it was given as the reason for the medical certification of just 1,407 of these applicants (2.2%). And, just 55 physicians certified 45,252 of these applicants (71%). The conclusion that recreational users are exploiting the MMA, with the assistance of a few physicians, therefore seems inescapable. It is finally doubtful that voters expected spin-off industries such as card acquisition clinics and dispensaries to materialize along with billboards and commercials advertising their presence. Most of the questions answered by the appellate courts have been relatively narrow, e.g., we now know that the MMA should not have been applied retroactively, to pre-MMA cases, and that the affirmative defense created by the MMA cannot be asserted retroactively, i.e., one must at least have their physician’s certificate prior to committing the offense to which they wish to raise the medical use of marihuana as an affirmative defense, as opposed to a physician’s certificate obtained after the fact. We also know that dog kennels, for example, do not qualify as “enclosed, locked facilities” for the growing of medical marihuana. A decision as to whether cardholders may operate a vehicle with marihuana in their systems is expected at any time. One wouldn’t think this would be controversial as the MMA does except the crime of operating under the influence of drugs from those to which the medical use of marihuana may be asserted as a defense, but Michigan law criminalizes both operating under the influence of drugs and operating with any schedule one substance in one’s system and proponents of medical marihuana have argued that, because the latter does not require proof of impairment, and the use captured by urine tests may be quite historical, cardholders are effectively barred from driving at all. The most significant appellate decision to date came in August of 2011, when the Court of Appeals confirmed that, although registered caregivers (growers) can provide marihuana to their own (up to 5) registered patients (users), sales of marihuana remain illegal such that patients/users can’t sell to each other and caregivers/growers can’t provide, let alone sell, marihuana to any patients/users but their own, and in doing so enabled the prosecution of business transacted in dispensaries; it also endorsed the enjoining of dispensaries as public nuisances. In order to stop the individual abuses and align the MMA with the ballot-created expectations of the electorate, however, the legislature needs to act to a) remove the catch-all conditions such as chronic pain as predicates for the use of medical marihuana and/or b) take the certification decision out of the hands of private physicians and make it the prerogative of a medical board which will conduct a meaningful review of the medical histories and needs of applicants.