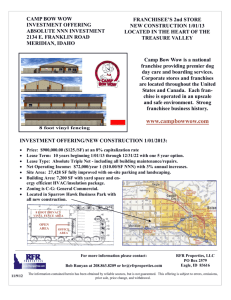

franchise territories: a community standard

advertisement