CAN A THIEF PASS TITLE TO STOLEN GOODS?

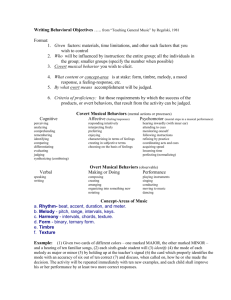

advertisement

6 S.Ac.L.J. Notes and Comments 439 CAN A THIEF PASS TITLE TO STOLEN GOODS? Caterpillar Far East Ltd v Cel Tractors Pte Ltd1 Suppose a thief steals a chattel that belongs to O and sells it to B. B is a bona fide purchaser for value without notice of the seller’s lack of title. When the truth is out, the thief is sent to prison.2 He is not worth suing. In practical terms, O’s only recourse is against B. O sues B for the recovery of the chattel, or its money equivalent.3 Both O and B are innocent (although one may have been more careless than the other). The question is who between them should suffer for the wrong done by a third party, the thief. One might be forgiven for thinking that the answer is quite clear: O should succeed because a thief cannot pass title to the goods he has stolen. However, when this set of facts was presented before the High Court in the recent case of Caterpillar Far East Ltd v CEL Tractors Pte Ltd, a contrary answer was given. There, both O and B were companies. O was in the tractor business and B was supposedly the largest spare parts dealer in Singapore.4 The chattels in issue were tractor spare parts. The theft and subsequent sale to B were carried out by a gang, whose members included two employees of O. Yong Pung How CJ held that B had acquired a good title. The scenario raises a conflict between two large interests. A balance has to be struck between O’s ownership interest and B’s commercial interest.5 Both need protection: There will be little order in society if title to property is not protected against theft; on the other hand, business can thrive only in an environment where there is some measure of security in commercial transactions. The starting point of the law has always been to uphold ownership interest at the expense of commercial interest. That starting point is embedded in the ancient maxim nemo dat quod non habet. It is also found in section 21(1) of the Sale of Goods Act,6 which provides: ‘Subject to this Act, where goods are sold by a person who is not their owner...the buyer acquires no better title to the goods than the seller had....’ There are exceptions to this rule. The better known exceptions7 are 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 [1994] 2 SLR 702. Cf the power conferred by s 388, Criminal Procedure Code, Cap 68,1985 Rev Ed, on the criminal court upon conviction of the thief. O would normally base his claim on the tort of conversion. His argument would be that title had never been divested from him. If it had, it is the law of restitution which tells O whether he can or cannot recover his title. Supra, note 1, at 705. So said Lord Denning in Bishopgate Motor Finance Corporation v Transport Brakes Limited [1949] 1 KB 332 at 336–7. See also R G Hammond, Person Property, Commentary and Materials (1990), at 173–4. Cap 393, 1994 Rev Ed. There are others: eg, the saving clause in s 21(2)(b). 440 Singapore Academy of Law Journal (1994) grounded in the principles of agency law8 and estoppel,9 and founded in statutory provisions such as sections 23, 24 and 25 of the Sale of Goods Act and sections 2, 8 and 9 of the Factors Act.10 Caterpillar was concerned with none of them; the case was decided instead on a very much expanded version of the ‘market overt’ exception to the nemo dat rule. For convenience, that expanded version will hereafter be called ‘the expanded rule’. Before turning to the expanded rule, its progenitor, the doctrine of ‘sale in market overt’, must first be examined. I. SALE IN MARKET OVERT A. The nature and scope of the market overt rule In England, the ‘market overt’ rule is currently found in section 22(1) of the United Kingdom Sale of Goods Act 197911 (‘UK SGA’). It reads: ‘Where goods are sold in market overt, according to the usage of the market, the buyer acquires a good title to the goods, provided he buys them in good faith and without notice of any defect or want of title on the part of the seller.’ The rule, although statutorily codified, is common law in origin. As a common law rule, it has existed since (at least) the time of Sir Edward Coke.12 Section 22(1), according to the Chief Justice in Caterpillar, represents the ‘statutory encapsulation’ of the common law rule;13 the common law informs the scope of section 22(1). The market overt doctrine may be briefly described as follows: If goods are purchased in a market overt, and provided certain other conditions are satisfied, the bona fide buyer obtains a good title, although the seller had none to give. This rule was originally evolved to promote commerce.14 The word ‘market’ is used in the sense of denoting a place where trading is conducted. Only certain markets are, in law, ‘markets overt’. Every shop within the City of London is by custom a market overt.15 Outside the City, 8 Ss 21(1), 62(2) of the Sale of Goods Act. 9 Ss 21(1), 62(2) of the Sale of Goods Act. 10 Cap 386, 1994 Rev Ed. This statute is a revised edition of the United Kingdom Factors Act 1889, 52 & 53 Viet, c 45, published under section 9(1) of the Application of English Law Act, cap 7A, 1994 Rev Ed. See also: section 21(2)(a) of the Sale of Goods Act. 11 1979, c 54. This provision can be traced to the same numbered section in the United Kingdom Sale of Goods Act 1893, 56 & 57 Vict, c 71. 12 Sir Edward Coke, The Second Part of the Institutes of the Laws of England (1662), at 713–4. Coke is generally thought to be an ‘economic liberal’: see D Little, Religion, Order and Law (1984 reprint), chapter 6 and the materials cited in bibliographical essay B therein. 13 Supra, note 1, at 706. 14 See supra, note 12, and W Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England (1766), vol 2, at 450; Sir John Comyns, A Digest of the Laws of England (1792), vol v, at 41–44. 15 The Case of Market Overt (1596) 5 Co Rep 83 b. 6 S.Ac.L.J. Notes and Comments 441 a market overt is an “open, public, and legally constituted market”.16 To quote from the learned editor of Benjamin’s Sale of Goods: ‘To be “legally constituted” the market must be one that has been created by statute or charter, or established by long continual user....’17 Not every sale made in a market overt gives the buyer a good title. There are requirements relating to how and in what circumstances the sale should be conducted. The sale must be conducted according to the usage of the market. To quote from the learned editor again: ‘The sale...must be made at the place of the market upon an ordinary market day and during the usual hours.18 The goods must be of a description which it is customary to find on sale in the market and must be openly exposed for sale there. The whole transaction, that is, the sale and delivery of the goods, must be begun and completed openly in the market....’19 It is thought that publicity ‘minimises the likelihood of the goods offered for sale being stolen property.’20 The rationale, developed in ancient times when commerce was slower in pace and smaller in scale, was this: The owner could and should pursue his goods to the market where it is well known that such goods are openly sold. If he does not bother, his title deserves to be defeated; the buyer of the stolen goods can legitimately say to himself: ‘[N]o person but the owner would dare to expose them for sale here, and therefore I have a right to assume that the shop-keeper has a right to sell them.’21 B. Does the market overt rule apply in Singapore? On this point,22 there was, before Caterpillar, no direct reported authority.23 Prior to the passing of the Application of English Law Act24 (‘the AELA’) in 1993, the market overt rule as codified in section 22(1) of the UK SGA was applicable to a particular case if it was received, for the purpose of 16 Lee v Bayes (1856) 18 CB 599 at 601. 17 4th ed, at para 7-018. See also E Tyler and N Palmer (eds), Crossley Vaines’ Personal Properly (5th ed), at 174–175. 18 Meaning between sunrise and sunset. This requirement stems from the need for publicity to safeguard the owner’s interest. As Lord Denning said in Reid v Metropolitan Police Commissioner [1973] 1 QB 551 at 560: ‘The goods should be openly on sale at a time when those who stand or pass by can see them. Thus it must be in the day-time when all can see what is for sale: and not in the night-time when no one can be sure what is going on.’ See also the view of Scarman LJ, ibid, at 564. 19 Supra‚ note 17, at para 7–019. See also Hargreave v Spink [1892] 1 QB 25 and the judgment of Scrutton J in Clayton v Le Roy [1911] 2 KB 1031. 20 Crossley Vaines’ Personal Property, supra, note 17, at 161. See also H Wilkinson, Personal Property (1971), at 171. 21 Crane v The London Dock Company (1864) 5 B & S 313 at 320, per Blackburn J. See also, ibid at 318–319, per Cockburn CJ. 22 See the excellent discussion by Dora Neo in ‘Application of English Law Act 1993: Sale of Goods and Nemo Dat’[1994] SJLS 40. 23 Cf the inconclusive dictum of Lai Kew Chai J in the High Court case of Commercial & Savings Bank of Somalia v loo Seng Company [1989] 2 MLJ 200, at 202. 24 Cap 7A, 1994 Rev Ed. 442 Singapore Academy of Law Journal (1994) that case, under section 5 of the Civil Law Act.25 Section 5 has been repealed by section 6(1) of the AELA. However, section 6(2) of that Act makes clear that in respect of a proceedings instituted or a cause of action accruing before the commencement of that Act, section 5 of the Civil Law Act will continue to apply. Caterpillar was apparently such a case: the series of thefts and subsequent sales were carried out in 1983 and the suit was instituted and the cause of action in conversion arose before the commencement of the AELA. This probably explains why the court referred to section 22(1) of the UK SGA although, and this is surprising, both the AELA and the Civil Law Act were not even mentioned in the judgment. Under section 5(3)(a) of the Civil Law Act, English law is received ‘subject to such modifications and adaptations as the circumstances of Singapore may require.’ One would be hard put, given its technical meaning, to find a ‘market overt’ in Singapore. Whichever of two possible interpretations one takes of Caterpillar (which will be discussed two paragraphs away), it is clear that the Chief Justice did not think that the market overt rule, in its English form, is suitable for local application:26 ‘...in order for a sale to constitute a sale in market overt in the City [of London] certain conditions must be fulfilled. Equally plain is the fact that these conditions were delineated in an era and in circumstances far removed from a contemporary Singapore. It would scarcely be desirable or necessary, therefore, to import wholesale into the Singaporean context the rule of market overt as it has evolved within the English legal system, lest we become entangled with the specific characteristics of markets overt in England, which derive from circumstances alien to us.’ The legislature seems to have thought likewise about the unsuitability of the market overt rule. While the AELA makes clear that the UK SGA 1979 is to apply in Singapore, it expressly excluded, inter alia, the reception of section 22.27 The UK SGA 1979 minus (inter alia) section 22 now appears in our statute books as Sale of Goods Act, Cap 393, 1994 revised edition (‘Singapore SGA’).28 (Hereafter, a reference to just ‘SGA’ is to both the UK and the Singapore SGA.) 25 Cap 43, 1988 Rev Ed. A number of local cases have assumed that the UK SGA applies in Singapore: eg, Harrisons & Crosfield (NZ) Ltd v Lian Aik Hang [1987] 2 MLJ 286, Koh Teck Hee v Leow Swee Lim [1992] 1 SLR 905; Additive Circuits (S) Pte Ltd v Wearnes Automation Pte Ltd [1992] 2 SLR 23. 26 Supra, note 1, at 706. Words in brackets added. 27 S 4(2) and 1st Schedule, Part II, Item 10, Fourth Column. This exclusion was thought to be ‘a necessary modification’; this is apparent from the report of the Parliamentary Debates (see speech of Professor S Jayakumar made on the second reading of the bill: Parliamentary Debates Singapore, Official Report, Tuesday, 12th October 1993, Vol 61, No 7, at 612) and from section 4(1) of the AELA itself. 28 The publication of the revised edition of the UK SGA 1979 is authorised by s 9(1) of the AELA. 6 S.Ac.L.J. Notes and Comments 443 The position for two categories of cases may be summarised thus: (1) For cases which attract the application of the Singapore SGA, the buyer cannot avail himself of a statutory market overt rule because the rule has been omitted from that Act; (2) It is unclear if section 22(1) of the UK SGA is applicable in cases, like Caterpillar, which are still governed by the old section 5 of the Civil Law Act. Caterpillar can be interpreted in two possible ways. The first is that it proceeded on the basis that section 22(1) does not apply in Singapore, and that the decision was reached by applying a newly evolved common law principle. If so, the common law principle it enunciated, or on which it was decided, would have to be considered.even in cases falling under category (1). The second possible interpretation is that the Chief Justice did apply section 22(1) but he interpreted it to suit local circumstances. On this interpretation, what Caterpillar decided is obviously of no relevance in category (1) cases. It is unclear which approach the court actually took.29 If the first interpretation is true to what the court intended, it is submitted that the decision cannot be justified. Under section 3(1) of the AELA, English common law, so far as it was part of Singapore law immediately before the commencement of the AELA, shall continue to be part of Singapore law. It may be argued that the common law market overt rule was received under the Second Charter of Justice 1826 and therefore still forms part of Singapore law today. There are two main arguments30 and one incidental observation against that view. The first argument is founded in section 3(2) of the AELA, which qualifies the earlier sub-section. It states that English common law is received ‘so far as it is applicable to the circumstances of Singapore and its inhabitants....’ As noted, the market overt rule, in the English common law form, fails to pass muster. It can perhaps be said that the court in Caterpillar was modifying English common law to suit local conditions. However, as will be demonstrated later, the rule applied in Caterpillar is so drastically different from the market overt rule that to call it a modification of that rule seem somewhat euphemistic. More importantly, it runs against the second argument that follows. The second argument is based on the supremacy of statutory law over common law. Section 21(1) of the SGA states a positive nemo dat rule and that statutory rule is said to be ‘subject to the Act’. This means that (i) the statutory nemo dat rule is qualified and (ii) the qualifications must be 29 The court held, rather vaguely, that ‘the principles underlying the rule of market overt are germane to the circumstances of the present case’(supra, note 1, at 706) and went on to apply the ‘rationale of the market overt rule’ (supra, note 1, at 707). Emphasis added. 30 There is the possibility of this third argument: it is conceptually wrong to proceed as if there were two rules of market overt — the statutory and the common law. Insofar as s 22(1) is an encapsulation of the common law market overt rule, there is only one rule; the common law rule is subsumed into s 22(1). They must therefore stand or fall together. 444 Singapore Academy of Law Journal (1994) recognised by the Act. Can the common law market overt rule qualify the statutory nemo dat principle? The answer has to be in the negative because generally common law cannot override a statutory rule. It is true that a statute may recognise a common law rule and in addition confer on it the ability to override another statutory rule.31 It may therefore be argued that the common law market overt rule is a ‘special common law...power of sale’ under section 21(2)(b) of the SGA and that as such, it is invested by that section with the ability to override the statutory nemo dat rule. This argument was raised but convincingly rejected in Queensland (whose Sale of Goods Act 1896 contained an equivalent of section 21(2)(b) of the SGA) in the case of Sorley and Stirling v Surawski.32 Compelling reasons were given. Macrossan CJ held that the common law did not recognise in thieves a power to sell the goods they had stolen. The special ‘common law...power of sale’ referred to in the Queensland’s equivalent of section 21(2)(b) of the SGA must be a lawful power of sale, such as that which a pawnee is given at common law upon default of payment of loan.33 As Stanley J noted, if the thief has the legal power of sale of stolen goods, his sale is lawful, which means he cannot be sued for it. This cannot be right for it is indisputable that the owner has a cause of action against the thief for conversion.34 Lastly, one may also observe that if the first interpretation is correct, it is somewhat odd, given that the legislature has now made explicit the inapplicability of the statutory market overt rule in Singapore, for the judiciary to move in the opposite direction by expanding its common law equivalent. II. THE EXPANDED RULE A. Its scope The scope of the expanded rule is unclear from the judgment. For that reason, it is difficult to set out its limits and its requirements. Given this, and the fact that the expanded rule was intended as a sort of derivative of the English market overt rule, it is proposed instead to examine how each of the main requirements of the English market overt rule is modified under the expanded rule. The first, it will be recalled, is that the sale must be made in a ‘market overt’, a term which refers (a) to a place (b) which has acquired the legal status of a market overt. The second is that the goods must be of a type 31 Cf section 62(2) of the SGA, which preserves the applicability of common law rules but only so far as they are not inconsistent with the SGA. 32 [1953] QSR 110. See K C T Sutton, Safes and Consumer Law in Australia and New Zealand (3rd ed), at 355–359. 33 Supra, note 32, at 114. 34 Supra, note 32, at 117. 6 S.Ac.L.J. Notes and Comments 445 normally sold in that market. Under the expanded rule, it would appear that it suffices if there is, loosely speaking, a ‘regular and open market’ for the goods in question. The term ‘market’ is used to denote not a specific locality but, it seems, a commercial state of affairs, namely, the existence of supply and demand. In Caterpillar, a member (called PW8’ in the judgment) of the gang of thieves had apparently some experience in the sale and disposal of spare parts. He found the defendant company listed in the Yellow Pages and contacted their sales director. He represented himself as a director of ‘Unibone Enterprises’, a company about which the judgment tells us very little. The negotiations were conducted on the telephone and at the defendants’ office. The goods were delivered by PW8 to the defendants’ premises. Although the sales were not made in any sort of market-place, it was held that there existed in Singapore ‘a regular and open market’ for the goods. This conclusion was apparently drawn from the fact that it was well known in the trade that the spare parts in issue were frequently bought in Singapore from independent suppliers (both in and out of Singapore). The market (in the conceptual sense of supply and demand) was open and regular, it seems, because most in the trade knew of the existence of and traded with such independent suppliers. It is unclear how seriously the requirement of a ‘regular and open market’ was intended as an obstacle to a buyer’s acquisition of title; the looser it is interpreted, the easier it will be for the buyer to obtain a good title.35 The third broad requirement of the market overt rule is that the sale must be conducted in a certain manner and at a certain time. As we saw, this requirement, in its odd way, provides some justification for depriving the owner of his title. The judgment does not say if there is any such requirement under the expanded rule. The sales were said to be ‘open’ not in the sense of visibility but by reason mainly of the lack of reason for suspicion on the buyer’s part. It is doubtful if this observation meets more than the next requirement. The fourth requirement of the market overt rule is that the buyer must be a bona fide purchaser without notice of the defect or lack of title on the part of the seller. This is also required under the expanded rule. In Caterpillar, it was held that the defendants were bona fide purchasers. The bona fide requirement appears to assume a central role in the expanded rule. However, this requirement is the common denominator of almost all the other recognised exceptions to the nemo dat rule; it has never and cannot be sufficient in itself to defeat that rule. Hence what distinguishes the 35 The Chief Justice took judicial notice of the fact that Singapore is a thriving ‘freeport and busy trading centre for all kinds of goods within the region.’ (Supra, note 1, at 707.) Does this mean that it is not difficult to establish a ‘regular and open market’ for most goods? There is no reason to think that the concept of ‘a regular and open market’ is inherently restricted to new goods. Some second-hand goods, like cars, are often and openly sold; and some goods, like antiques, are almost by definition second-hand. 446 Singapore Academy of Law Journal (1994) expanded rule from the other exceptions and forms the core of the expanded rule is the idea of a ‘regular and open market’. Considering the significance of its role, the judgment, with respect, ought to have given a clearer explanation of that concept. If it is given a wide meaning, the expanded rule may come near to swallowing up all the other nemo dat exceptions. B. Is the expanded rule sound? The expanded rule, in making it easier for commercial interest to prevail over ownership interest, brings into question the orthodox priority given to the latter over the former. The robust approach of the court was grounded in this set of policy considerations: ‘...the relative facility of transfer of property in goods may in various instances make a ‘loser’ of the original owner of goods which are converted, but such an ‘evil’ (if indeed one can even call it that) is counterbalanced by the general practical virtues of a system that facilitates the passing of property in goods. It should also be pointed out that in the majority of cases, the original owner of the goods is covered by insurance, whereas it may be difficult for the innocent purchaser to enforce his remedy (and even if he is able to do so, it will be expensive)36....The other point which should be made is that, in more cases than not, goods are stolen at least partly as a result of the carelessness of the owner or his servants, or at any rate their failure to take proper precautions to safeguard property. That this was so in the present case is manifest from the evidence led.’37 These statements would no doubt enthral believers in the economic analysis of the law. In a very superficial form (my failing as an economist will be obvious), the issue may be formulated thus: Is a legal rule (the nemo dat principle) which imposes a general obligation to enquire into the seller’s title more efficient than one (the expanded rule) which imposes a general obligation to protect one’s property from theft? The cost and benefit of each rule would have to be weighed; the rule to prefer is that which, in the totality of cases, is likely to produce a greater net gain. In the absence of empirical evidence, it is doubtful that this balancing exercise is possible of performance other than intuitively.38 In any event, we have to be conscious 36 Supra, note 1, at 707. 37 Supra, note 1, at 708. 38 It is not denied that law making, whether judicial or legislative, will always, as Hart and McNaghten say, be based on experience and reflection rather than on some absolute truths. (‘Evidence and Inference in the Law’ in D Lerner ed, Evidence and Inference (1959), at 70). My point is that the soundness of a judgment must depend on how much we know and that on the policy issue at hand, little relevant data is available. Consider this assumption by the Chief Justice, supra, note 1, at 707: ‘It is clear that great public inconvenience and confusion would result if the rationale of the market overt rule could not operate.’ With respect, it is not obvious that the obscure market overt rule has ever contributed so much to stabilising commerce. 6 S.Ac.L.J. Notes and Comments 447 that tilting the balance in favour of the bona fide purchaser of stolen goods is likely to incur costs (a) in the form of increased insurance premiums39 and (b) as a result of making thieves ‘more confident of finding purchasers’.40 Such externalities will affect the efficiency of the expanded rule. There is a perhaps more fundamental point. The formulation of any legal rule must be done with an awareness of its impact on other legal rules. Legal rules must be consistent. The expanded rule does not fit with what the law is commonly understood to be. Three inconsistencies may be noted. The Chief Justice found in the case before him that the owners did not take sufficient precautions to safeguard their goods. It is not clear what legal significance was attached to that finding for the court conceded that there is ‘no legal duty in general to prevent theft of one’s property.’ The relativity of fault may be the principle underlying some of the nemo dot exceptions but it has never been a rule as such.41 Lord Macnaghten stated settled law in Farquharson Bros v C King & Co:42 ‘The right of the true owner is not prejudiced or affected by his carelessness in losing the chattel, however gross it may have been....If a person leaves a watch or a ring on a seat in the park or on a table at a cafe and it ultimately gets into the hands of a bona fide purchaser, it is no answer to the true owner to say that it was his carelessness and nothing else that enabled the finder to pass it off as his own.’ This view is not contradicted by the expanded rule; the latter will not allow the bona fide buyer to get a good title to the watch and the ring unless he bought it in a ‘regular and open market’. However, the easier we make proof of a ‘regular and open market’, the easier it is for a bona fide purchaser to deprive the owner of his title. If the expanded rule is to remain law and if the security of ownership which Lord Macnaghten spoke of is to be taken seriously, we cannot afford to let the concept of ‘regular and open market’ remain woolly. There is a second inconsistency: Theft is as bad as, if not worse than, obtaining goods fraudulently. There is no reason why a thief should be more capable of passing title than a fraudster. In the well-known case of Cundy v Lindsay,43 F deceived O into thinking that F was ordering cambric handkerchiefs on behalf of a reputable business firm. On the basis of that 39 P S Atiyah, ‘Law Reform Committee: Twelfth Report’ (1966) 29 MLR 541, at 542. 40 Words of Lord Donovan quoted in H Wilkinson, Personal Property (1971), at 172, footnote 46. 41 P S Atiyah, The Sale of Goods (8th ed), at 353, footnote 41. 42 [1902] AC 325 at 335–6. It is true that Lord Macnaghten excluded from this statement of law a sale made in a market overt. However, it has to be stressed that the market overt rule he had in mind is very much narrower that the expanded rule. 43 (1878) 3 App Cas 459. 448 Singapore Academy of Law Journal (1994) deception, O delivered the goods to F on credit. F sold the goods to B. B was a bona fide purchaser. When O uncovered the true facts upon F’s failure to pay for the goods, O sued B for conversion. O succeeded. The House of Lords reasoned that since O was mistaken as to the identity of the other contracting party, no contract was formed between F and O; as such, F did not obtain any title to the goods to pass to B. If F had been less sophisticated and had resorted to theft instead of fraud, surely he should not thereby acquire a better ability to pass title. If there had been a ‘regular and open market’ (in the Caterpillar sense) in cambric handkerchiefs, a possibility which the reported facts do not rule out,44 would the expanded rule not have achieved an opposite result in Cundy v Lindsay? The third inconsistency is this: Traditionally, lawyers do not take kindly to the idea of a thief being able to pass title to stolen goods. The anachronistic market overt rule was barely tolerated even though, having an obscure status in the law of sale of goods, that idea came to life only in a minor way. The tenacity of the traditional belief is well illustrated by the way the courts have interpreted section 25(1) of the UK SGA, which appears as section 25 of the Singapore SGA, and the similarly45 worded section 9 of our (as well as the UK) Factors Act (more popularly known as ‘the buyer in possession’ exception to the nemo dat rule). Section 25(1) states: ‘Where a person [B1] having bought or agreed to buy goods obtains, with the consent of the seller [S], possession of the goods..., the delivery or transfer by that person [B1]...of the goods...under any sale...to any person [B2] receiving the same in good faith and without notice of any...right of the original seller [S] in respect of the goods, has the same effect as if the person [B1] making the delivery or transfer were a mercantile agent in possession of the goods...with the consent of the owner [O].’ [Emphasis and words in square brackets added.] The effect of treating B1 as a mercantile agent in possession of the goods with the consent of the owner is that section 2(1) of the Factors Act would then apply. If section 2(1) applies, the sale by B1 to B2, if it was made by Bl ‘when acting in the ordinary course of business of a mercantile agent, shall...be as valid as if he [B1] were expressly authorised by the owner of the goods to make the same; provided that the person taking under the disposition [B2] acts in good faith, and has not at the time of the disposition notice that the person making the disposition has not authority to make the same.’ If B1 is treated as having been expressly authorised by the owner to sell the goods, the sale, under the law of agency, would be binding on the latter. 44 The facts, however, do rule out the applicability of the English market overt rule because, to begin with, the sale was not conducted in a market overt in the sense of an open, public and legally constituted market. 45 The difference is not relevant to the present discussion. 6 S.Ac.L.J. Notes and Comments 449 Paradoxically, despite the efforts to create an intricate web to protect ownership, there is an apparent loophole which may allow a thief to deprive the owner of his title. If a thief (S) sells a stolen chattel to B1 and B1 sells it to B2, section 25(1) may well defeat the owner’s (O’s) title to the chattel by this argument: Since i) B1 was a buyer in possession of goods, ii) which possession was obtained with the consent of the seller, S (ie, the thief), and iii) B1 delivered the chattel to B2, iv) who acted bona fide and without notice, Bl is deemed to be a mercantile agent in possession of the chattel with the consent of O. In that capacity, B1 is able to pass a good title to B2 under section 2(1) of the Factors Act, thus defeating O’s title. This factual configuration (but with an added number of sub-buyers) was before the House of Lords in National Employers’ Insurance v Jones.46 The House was clearly disturbed by the prospect that a thief could pass a good title if section 25(1) of the UK SGA and section 9 of the UK Factors Act are read literally. It therefore chose to interpret the provisions in accordance more with their spirit than their letters. It essentially construed the word ‘owner’ appearing in those provisions to mean ‘seller’. This means that the consent which B1 is deemed to have is that of the person (S) who had entrusted the goods to him. If, as was the case in National Employers’ Insurance, S happens not to be the owner of the goods, section 2(1) of the Factors Act would not be triggered off to defeat the owner’s title. What was stolen in National Employers’ Insurance was a car. It was sold to the last buyer by a car dealer (himself an innocent purchaser). There seems as much reason to say that there was a regular and open market for cars in that case47 as to say that there was a regular and open market for vehicle spare parts in Caterpillar. An application of the expanded rule to the facts in National Employers’ Insurance would most likely lead to a result opposite to the outcome of that case.48 We find, instead, the Law Lords straining against statutory language to prevent a thief from passing title to stolen goods. Judges in New Zealand49 and Canada50 have done likewise. Our High Court, on the other hand, is expanding (depending on which interpretation one takes) either a common law rule or the scope of section 22(1) of the UK SGA to allow a thief to do exactly that. From a nationalistic view-point, these observations are of no consequence; we ought to have the courage and conviction to do what we think is right. It is certainly true that purely from the policy perspective, although primacy of 46 [1988] 2 WLR 952. The issue which this case decided had caused much academic debate: Cornish (1964) 27 MLR 472, at 477-8; Atiyah, The Sale of Goods (6th ed), at 255–6; Battersby and Preston (1975) 38 MLR 77. Cf Powles, (1974) 37 MLR 213. 47 And arguable also in Lim Kim Cheong v Lee Johnson [1993] 1 SLR 313. 48 Cf the position had the sale been made by a hirer instead: see Halsbury’s Laws of England, 4th ed, Vol 22, para 268. 49 Elwin v O’Regan and Maxwell [1971] NZLR 1124. 50 Brandon v Leckie (1972) 29 DLR (3d) 633. 450 Singapore Academy of Law Journal (1994) the nemo dat rule is entrenched in Anglo-American legal systems,51 no one can say that it is indisputably sound. Indeed, the French have taken a different (but not completely opposite) starting point from the AngloAmerican,52 and in 1966, the English Law Reform Committee had proposed (albeit it did not result in legislation) a reform which resembles, to some extent, the law as enunciated in Caterpillar.53 However, courage to innovate must be tempered with caution. There is a limit to the extent to which the statutory nemo dat rule can be judicially, as opposed to legislatively, eroded. Each person, looking behind the mystery of the latin, will have his or her own view on its desirability and fairness, but whether we like it or not, the nemo dat rule is deeply ingrained in our law. It forms the basis of so many of our judicial and statutory rules. These rules interconnect like threads weaving a pattern; if a string is too vigorously tugged, the pattern goes awry. May we look to the Court of Appeal for a clearer picture? HO HOCK LAI* 51 Under the American Uniform Commercial Code, the thief would also be unable to pass any title to a purchaser even though he may have bought the goods in good faith. This is because the thief has a void title and section 2–403(1) only allows a person with a voidable title to pass a good title to a good faith purchaser for value. See: J White and R Summers, Uniform Commercial Code (3rd ed), at 173. 52 Article 2279 of their Civil Code states: ‘En fait de meibles la possession vaul title’; ‘In matters of personalty, possession is equivalent to title.’ This is however qualified thus: ‘Nevertheless, one...from whom was stolen a thing...may claim it during three years, counting from the day of the loss or theft, against the one in whose hands he finds it, saving to that one his recourse against him from whom he holds it.’ Article 2280 goes on to state: ‘If the present possessor of a thing stolen or lost bought it at a fair or at a market...the orginal owner may have it returned to him only by reimbursing the possessor for the price which it cost him.’ (The French Civil Code, translated with an Introduction by John H Crabb (1977), at 408.) 53 See the commentaries of A Diamond (1966) 29 MLR 413 and P Atiyah, ibid, at 415 on the Twelfth Report of the UK Law Reform Committee on The Transfer of Title to Chattels, Cmnd 2958. * LLB (NUS); BCL (Oxon); Advocate and Solicitor (Singapore); Lecturer, Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore. I am very much indebted to Barry Crown, Peter English, and Dora Neo for their comments on the draft of this note; they are of course to be exonerated from responsibility for any error in the views that I have expressed.