A Study of the Bhagavadgita

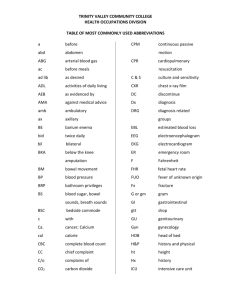

advertisement