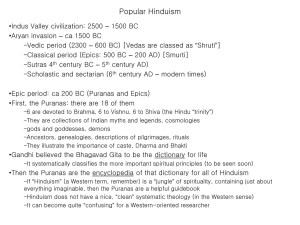

The Bhagavad Gita - Theosophical Society in America

advertisement