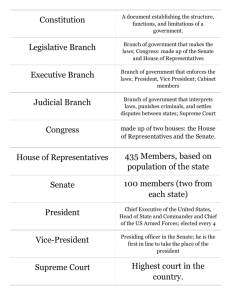

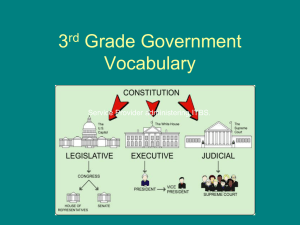

The Legislative Process: How a Bill Becomes a Federal Law

advertisement